Ed. Note: This is part one of a three-part series, “Young, gifted and black.” For part two, on activists, click here. For part three, on artists and entrepreneurs, click here.

This Black History Month, we are taking a look at the chapters still to be written — and the inspiring UC students and recent grads who will help write them.

These young scholars and scientists are already making a difference in their communities and the wider world, turning their research into a potent force for social justice and equity.

Drawing on their own experiences and cultural perspectives, these change-makers are working to expand knowledge in areas from education to climate change. And along with racking up their own impressive accomplishments, they are helping bring a new generation of researchers along.

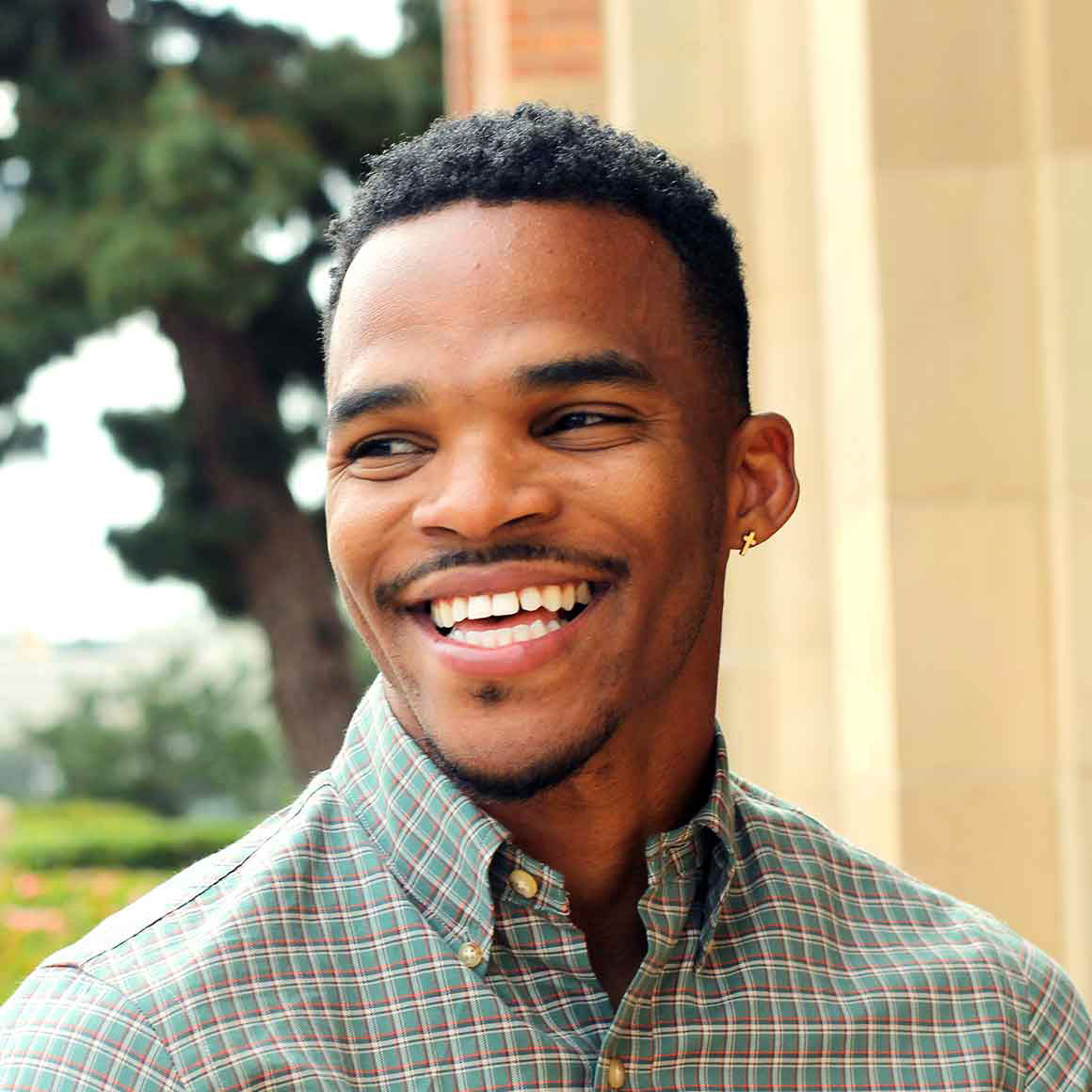

Terry Allen, policing public schools

Campus: UC Berkeley, UCLA

Major: Rhetoric

Hometown: San Francisco, Calif.

UCLA graduate student Terry Allen calls his work — on the impacts of policing on public education — “me-search” for its deep roots in his own experiences and observations.

Allen grew up in San Francisco’s Hunters Point neighborhood, a place of concentrated poverty and disadvantage. The strong police presence in the neighborhood was a source of ongoing tension with residents, especially youth.

In his community, “going to school was a rarity,” he said. “Many kids dropped out in middle school. They just gave up on their education.”

But Allen, who loved school from an early age, was different. He excelled and the community supported him.

That education took him farther than he could have imagined: to a degree in rhetoric at UC Berkeley, and from there to an internship in President Barack Obama’s White House, where he was tapped to join the president’s travel detail. The 21-year-old kid from a blighted neighborhood suddenly found himself accompanying the president and first lady on official events around the country. “It was dreamlike,” he said. “That simply wasn’t within the palette of what I had imagined possible.”

Now a Ph.D. student with UCLA’s Graduate School of Education, Allen is working to address inequalities in education that deter students like his classmates from staying in and thriving at school.

Allen recently published research looking at the police presence in public schools and how those interactions affect learning. The findings, produced by UCLA Million Dollar Hoods Project, run by the Bunche Center for African American Studies, suggest that measures intended to make school feel safer may be having the opposite effect for many students.

At Los Angeles Unified School District, which has the highest police presence of any school district in the country, a quarter of the youth cited or arrested are still in elementary or middle school. Many run-ins are over non-criminal, garden-variety adolescent behavior, like getting into arguments or being late for school.

Place your name in every hat. Be open to things you never thought possible.

“When students are going to school and feeling targeted and criminalized, what does this mean for their sense of safety and ability to achieve?” Allen asked. The report, which recommends resources be directed toward connecting youth with community programs, is being used by LAUSD officials as part of a working group on school reform.

Allen said his own life has taught him to be bold in stepping up to life’s opportunities. “Place your name in every hat. Whether its scholarships, or college, or jobs — just go for it. Be open to things you never thought possible, and be willing to trust yourself.”

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, defending science, the seas and us

Campus: UC San Diego

Major: Marine biology (M.S. ’09, Ph.D. ’11)

Hometown: Brooklyn

As a marine biologist, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson works to protect what is under threat: not just oceans and the vulnerable people who live near them but, lately, science itself.

The UC San Diego graduate, founder/CEO of the consultancy Ocean Collectiv and adjunct professor at New York University, was instrumental in organizing the inaugural March for Science, which drew more than a million marchers in Washington, D.C., and over 600 cities across the world.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson speaking at the World Science Festival in Times Square with Andy Revkin in 2017.

“I have marched against police brutality and mass incarceration, and for black lives,” she wrote in Scientific American. “I have marched against pipelines and for sane climate policy. I have marched for women, for a living wage, and for immigrants and refugees. But I had never helped organize a march. And of all the causes, I never, ever thought my first would be science.”

Johnson studies the role of marine ecosystems in meeting the health and safety needs for a variety of communities vulnerable to climate change.

As a graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Johnson focused on sustainably managing coral reefs. She found that her research was critically informed by the perspectives of local fishermen, scuba divers and others who interact in a regular basis with the marine environment.

“Counting fish is important, but what I really needed to do was listen to fishermen. And so everything I did from then on was focused on that,” said Johnson, recalling her “Aha” moment in front of a packed house at the Robert Paine Scripps Forum for Science, Society and the Environment late last year. “Ocean conservation is about people. It's not about fish, obviously. No, fish are doing their damnedest. Corals are trying really hard to not die. It's humans that are the problem.”

Johnson has already served in a variety of policy capacities: helping to draft the National and Oceanic Atmospheric Administration's involvement in the National Ocean Policy Implementation Plan, serving as an environmental scientist for the EPA’s regulatory analysis and policy team, and leading the Caribbean’s first successful island-wide ocean zoning project as executive director of the Waitt Institute. In 2017, she began her own consultancy firm, Ocean Collectiv, to bring policy experts together to help create healthier oceans for the underserved people who live near them.

You are not just scientists; you are also citizens.

In February of 2017 Johnson joined the March for Science as the national co-director of partnerships and helped launch the highly visible, first-of-its-kind march. It was a response to threats to the integrity of government science and drastic budget cuts to the National Institutes of Health and the EPA.

For Johnson, this is a fundamental responsibility for a researcher. “You are not just scientists; you are also citizens. There are a lot of things to be calling your representatives about right now. Funding for science could be one of them,” Johnson told students at Robert Paine Scripps Forum for Science, Society and the Environment. “Your science matters, and so does your voice.”

Kenly Brown, reexamining education

Campus: UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara

Major: African American studies

Hometown: Raleigh, North Carolina

Kenly Brown is a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley and a budding social scientist with a radical idea: that research participants should recognize themselves as they are described in her work. Growing up in Colorado as the daughter of a minister serving a primarily white congregation, Brown saw first-hand the importance of seeing oneself centered and represented in a social context.

“The belief is, if you just bring black and brown girls into white spaces, they'll be able to succeed,” Brown said. “They’ll be okay, they’ll be able to assimilate. But my own experience, you still feel exclusion, you still feel provisional.” And, as a side effect, pulling students out of their communities in an effort to provide them with more resources elsewhere strips those communities of their members, and talent.

“Why can’t we just give these communities more resources?” Brown asks.

This question of resources is particularly pressing in the area of continuation schools, the subject of Brown’s dissertation in which she examines black girlhood, institutional violence and alternative schooling. Continuation schools are alternatives for students who are seen as disciplinary or academic problems. Purporting to solve a problem by moving students to different schools, the result is a modern form of segregation: according to Brown’s research, the students who are shuffled into these schools are overwhelmingly underrepresented minority students coming from majority white institutions. Their white peers are seldom sent along the same path. Continuation schools rarely provide sufficient education and training for their students to succeed, nor do they help students overcome personal backgrounds that are often weighted with trauma.

Entering these schools for her work, Brown has taken a radical approach as a social scientist — she wants the students to participate, and see themselves, in her work. She provides space for girls attending these schools to socialize, takes them to lunch, and makes sure they see and can comment on her work.

It may not seem like a remarkable shift, but as Brown says, “Mainstream ethnography is often a violation.” Social scientists enter and exit communities without historical context, providing a distorted view. For Brown, influenced by a tradition of black feminism and historically underappreciated scholars, that approach makes no sense.

I’m hoping my work is out there in the world, and girls can read and see themselves in it.

“I’m hoping my work is out there in the world, and girls can read and see themselves in it,” Brown said. “They understand what they are going through, that they don’t have the same access [to resources]. They know their life. I am trying to join them in conversation with each other.”

By tapping into students’ experiential knowledge, Brown hopes to help continuation school students, and her own students she teaches at UC Berkeley, understand how issues of identity and systems of inequity and violence play out in their lives.

“I will continue to call out institutional violence, the way our systems are profiting off people’s lives. The students, teachers and teenagers I work with keep me accountable.”

Muryam Gourdet, changing ideas of who gets to do science

Campus: UCSF

Major: Biochemistry

Hometown: Novato and Petaluma, Calif.

As an undergraduate, Muryam Gourdet was pursuing a pre-nursing curriculum, like others in her family had. But her course changed during a lecture about general protein structure.

“She [the lecturer] used a piece of paper as an analogy to describe different protein structures. The way it folds and crumples is very specific, based off of interactions between the amino acids,” Gourdet said. “That just blew my mind. I wanted to learn more. That’s when I became engaged in that class.”

It would push science faster if we had different eyes and perspectives facing our problems.

Now a third-year Ph.D. candidate in the lab of biophysicist Geeta Narlikar at UC San Francisco, Gourdet studies how molecular motors that interact with nucleosomes, DNA-protein structures that are foundational elements of life, function.

Gourdet’s passion is contributing to the forward march of knowledge, but she’s also committed to changing who gets to do science.

“Undergrad, I worked full-time at Ikea. That could have been my life,” she said. “Not until I started my master’s did I learn that doing research can be an actual job.”

Gourdet is working to educate young women and people of color of the many career options in science, and how important it is that their perspectives are included. She has worked to get postdocs and grad students from UCSF to Holy Names University, her undergraduate alma matter, for a biology careers club, and partnered with Scientists 4 Diversity to provide tours of labs for younger students. She has also worked on outreach to community college students. She is currently partnering with a continuation school in Berkeley to expose students to scientific careers.

On her own campus, Gourdet is working to increase peer support for graduate students and spearheading an effort to start the first black student union for graduate students at UCSF.

“Many people don’t realize the value of their experience and how it can be applied in different fields of science,” Gourdet said. “I think it would push science faster if we had different eyes and perspectives facing our problems.”

Cover photo: The Million Dollar Hoods team with Terry Allen first row, third from left. Million Dollar Hoods is the flagship research project of the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies that, with community, maps the human and fiscal cost of incarceration in Los Angeles and beyond. Photo courtesy Terry Allen