Andy Murdock, UC Newsroom

All scientists follow in the footsteps of earlier scientists. Steve Beissinger, Jim Patton and their colleagues at UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology take this more literally than most. Since 2005, they have tried to walk exactly where their predecessors walked 100 years ago, in an attempt to understand where California’s native animals are heading in a warming climate.

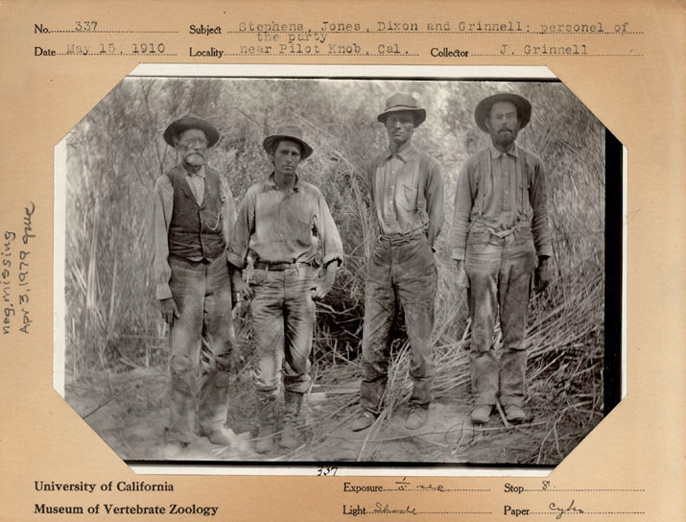

Joseph Grinnell, the first director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, was a prodigious collector and famously detailed note taker.

Between 1904 and 1939, Grinnell and his students crisscrossed California in his Ford Model T, painstakingly surveying and collecting mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians from more than 700 locations from Yosemite to Mount Lassen to the Mojave Desert, spanning the diverse habitats of the state. This work resulted in roughly 100,000 specimens, 74,000 pages of field notes and some 10,000 photos.

The word “biodiversity” had yet to be coined, the modern methods of ecological research were just being born, and there was no concept of DNA at the time, but Grinnell knew the work he and his students and colleagues were undertaking was important.

The value, Grinnell said in 1910, will not be realized “until the lapse of many years, possibly a century, assuming that our material is safely preserved. And this is that the student of the future will have access to the original record of faunal conditions in California and the west.”

“We are those students of the future,” said Beissinger.

Credit: Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, UC Berkeley

100 years of change

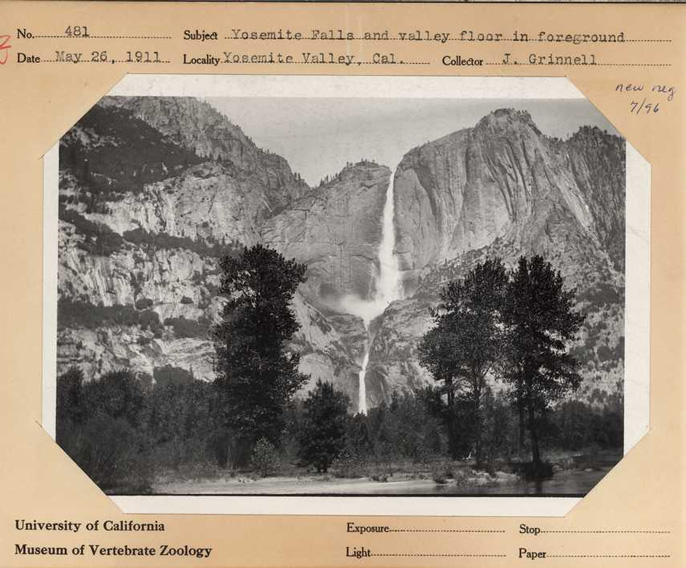

Today, as the U.S. National Park Service celebrates its 100th anniversary, Beissinger, Patton and colleagues at UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology are following Grinnell’s path across the iconic landscapes of Yosemite, Death Valley, and other national parks in California, repeating animal surveys in the same locations Grinnell sampled to find out what has changed — and, perhaps more importantly, what we can expect to see in the future as the climate continues to warm.

A century later, one big picture result from the Grinnell resurvey work tracks with multiple other studies from around the world: Many species are on the move as the planet warms, a fact that President Obama called out in his visit to Yosemite in June 2016.

“Here in Yosemite, meadows are drying out. Bird ranges are shifting farther northward. Alpine mammals like pikas are being forced farther upslope to escape higher temperatures,” said President Obama, referencing findings from the UC Berkeley group’s work.

“I was thrilled he had heard of our research,” said Beissinger. “He even knew about small alpine mammals!”

Obama expressed concern about what climate change would mean for our national parks: no glaciers in Glacier National Park, no joshua trees in Joshua Tree National Park.

“That’s not the legacy I think any of us want to leave behind,” President Obama said. “The idea that these places that sear themselves into your memory could be marred or lost to history, that’s to be taken seriously.”

Credit: NPS Photo

The transforming national parks are a source of concern, but the fact that they have been mostly untouched for the better part of a century made them the top priority for UC Berkeley’s Grinnell Resurvey team.

“National parks haven’t changed much over time with regard to land use,” explained Beissinger. “In national parks, we’re mostly looking for a climate signal, expecting small mammals and birds to move upslope in the Sierras as global temperatures rise.”

In Yosemite, the resurvey team found that about half of the small mammal species had moved upslope from the time Grinnell collected them. Lower elevation species tended to expand their upper ranges to higher elevations, while higher elevation species retracted their ranges, following the snowpack upward.

The main effect observed by the UC Berkeley team isn’t coming from summers getting hotter, but from the milder winters.

“High elevation mammals that hibernate rely on snowpack for insulation,” explained Patton. “But winters have become warmer, with more precipitation falling as rain than snow.”

The range of other species hasn’t changed much over the past 100 years, and a few have even moved downslope. This came as no surprise to the resurvey team: ecosystems are complex, and temperature is only one factor that affects the niche in which a species can thrive. Species may also move based on other factors, including precipitation, wildfires, competition for resources, or to follow a food source that’s also on the move due to climate change.

Amid the overall global warming trend, the effect can be different on a local scale. The area around Mount Lassen has experienced some cooling and more rain on the local level over the past half-century. There the pattern of bird movement downslope found by the survey team was very different from the upslope movements they found in Yosemite, which has warmed and dried substantially.

“Climate change is lumpy,” said Beissinger.

Overall, the resurvey results are showing that the national parks have done their job and done it well.

“All of the small mammal species that Grinnell found 100 years ago are still there – in fact we even added the Inyo shrew to Yosemite’s list.”

The shifting goals of national parks

In 1915, UC Berkeley faculty and alums Stephen T. Mather and Horace M. Albright convened a meeting on the Berkeley campus that resulted in the legislation establishing the National Park Service in 1916. Mather became the first director of the National Park Service, Albright the second.

“Many of Grinnell’s students were the first biologists in the National Park Service, and they really established the ecological ethos in the early days of the parks,” said Patton.

Grinnell at the time stressed that national parks should not be small islands of preservation, but should be connected to other public lands and managed as part of a larger ecosystem.

Credit: Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, UC Berkeley

To Beissinger, there’s a crucial question facing the national parks today, 100 years after the U.S. National Park Service was born: What is the goal of national parks given the reality of climate change?

“Do we continue trying to make these parks like vignettes of early America, which until recently was the management goal of the National Park Service? Climate change now tells us that often this isn’t going to be possible,” said Beissinger.

The 1963 Leopold Report established a long-standing wildlife management approach for the national parks, seeking to provide “a reasonable illusion of primitive America,” but the illusion becomes increasingly difficult to maintain as more troubling signs of the effects of climate change grow apparent in the parks.

“We’re now faced with managing toward a future of constant change,” said Beissinger.

While climate change may make it impossible to maintain historic conditions in many national parks, Beissinger thinks the parks can still play an important role as refugia: places where species can survive in the face of a changing environment.

Beissinger and his colleagues are specifically looking to pinpoint the places where the climate isn’t changing quickly. It’s also important that refugia are connected, so species can move into them and move around as needed. Identifying these areas can help land managers prioritize their conservation efforts.

“This reemphasizes what Grinnell said: National parks shouldn’t be islands, but connected and managed in the larger context of the ecosystem,” said Patton.

In Grinnell’s footsteps to the future

When scientists create models to predict future distributions of species, most are forced to start with data on the present-day locations of species and then project distributions forward in time based on climate data. Reliable and thorough data from the past are rarely available to compare against that of contemporary locations.

Not so with California’s birds and mammals. Because of Grinnell’s detailed field notes, reliable data on species’ locations across California starts 100 years ago, providing a much better way to anchor the trajectory, and rich data for the statistical models used by researchers today.

“His field books are little goldmines,” said Beissinger.

Grinnell and his students tried to record everything they saw in their field notes. Not only would they take notes on animals trapped and collected, but also other species observed nearby, and counts of birds encountered along the way.

Here again, Grinnell proved his foresight.

“It is quite probable that the facts of distribution, life history, and economic status may finally prove to be of more far-reaching value than whatever information is obtainable exclusively from the specimens themselves,” Grinnell wrote.

Credit: Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, UC Berkeley

To Patton, both Grinnell’s work 100 years ago and the current resurvey project underscore just how valuable research museum collections are. UC Berkeley’s six natural history museums hold over 12 million specimens: plants, insects, fossils, human artifacts, vertebrates and more. With modern data analysis methods and the advent of sequencing techniques for ancient DNA, collections like these are a wealth of information today in ways never dreamed about when the museums were founded.

“The fact that we have historical material allows us to address questions we couldn’t even conceive of studying without it,” said Patton.

Grinnell’s meticulous notes have allowed UC Berkeley researchers to track down his survey locations, sometimes finding the exact same spot where a photo was taken 100 years ago.

“We’re not always able to walk in their footsteps, but they left us good documentation for the most part. In another 20 or 100 years, with the kind of data we’re gathering today, people will be able to walk exactly where we walked,” said Beissinger.

What they’ll see there is the question.

Major funding for the Grinnell Resurvey work is provided by the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, and the National Park Service.