Andy Murdock, UC Newsroom

You know them from the line across the kitchen counter and the swarm around your water faucet: Argentine ants. California sits atop a super-colony of these unwelcome houseguests, and new research suggests they may be doing more harm than previously suspected.

Argentine ants’ annoying habits aren’t purely domestic. Ants protect pests like aphids and mealybugs, which feed on important California crops like grapes and citrus. Argentine ants also drive out native species, in some cases having a negative impact on species that rely on native ants for food.

A study published this month in Biology Letters found that Argentine ants could be wreaking havoc in yet another way: as a vector for an insect virus known as Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) implicated in honeybee colony collapse disorder.

The impact of colony collapse disorder in California has been keenly felt by the state’s fruit growers. California produces roughly 80 percent of the world’s almonds, one of many California crops that rely heavily on honeybees for pollination. The current rate of colony loss is unsustainable, and commercial pollination costs have more than tripled in the past decade due to the limited supply of healthy honeybee colonies.

A bigger problem

But don’t break out the honey wine just yet. UC Berkeley professor Neil Tsutsui, who studies ant and bee interactions, cautions that the results of the recent study are interesting but preliminary.

“There's no evidence that the dicistrovirus found in Argentine ants does anything negative, and the presence of DWV in Argentine ants is only suggestive at this point,” says Tsutsui.

Even if beekeepers can exclude Argentine ants from honeybee hives — a difficult task — this would not be a complete solution.

“Beekeepers are more concerned about varroa mites,” says Elina Niño, assistant extension specialist in apiculture at UC Davis. Varroa mites are a known carrier of DWV, and have been a growing problem for beekeepers in the United States since the late 1980s. “Argentine ants can do considerable damage to bee colonies regardless of their potential to vector DWV. They feed on brood; but unlike mites, they carry the brood away and don’t stay in the hive.”

The problems for bees don't end at the hive; bees get around.

“Bees drift from hive to hive with some regularity, so it's easy for pathogens to spread among nearby colonies,” says Tsutsui. “Pathogens can also be transmitted among bees at flowers, even if they don't come into direct contact.”

Bees are facing numerous challenges today, including viral, bacterial and fungal pathogens, as well as pesticides and lack of adequate forage plants. The California drought is only making matters worse.

“Bees need water to drink, just like you and me,” says Niño. “It also contributes to a lack of forage. And bees need water for climate control in hives, where they use it for evaporative cooling.”

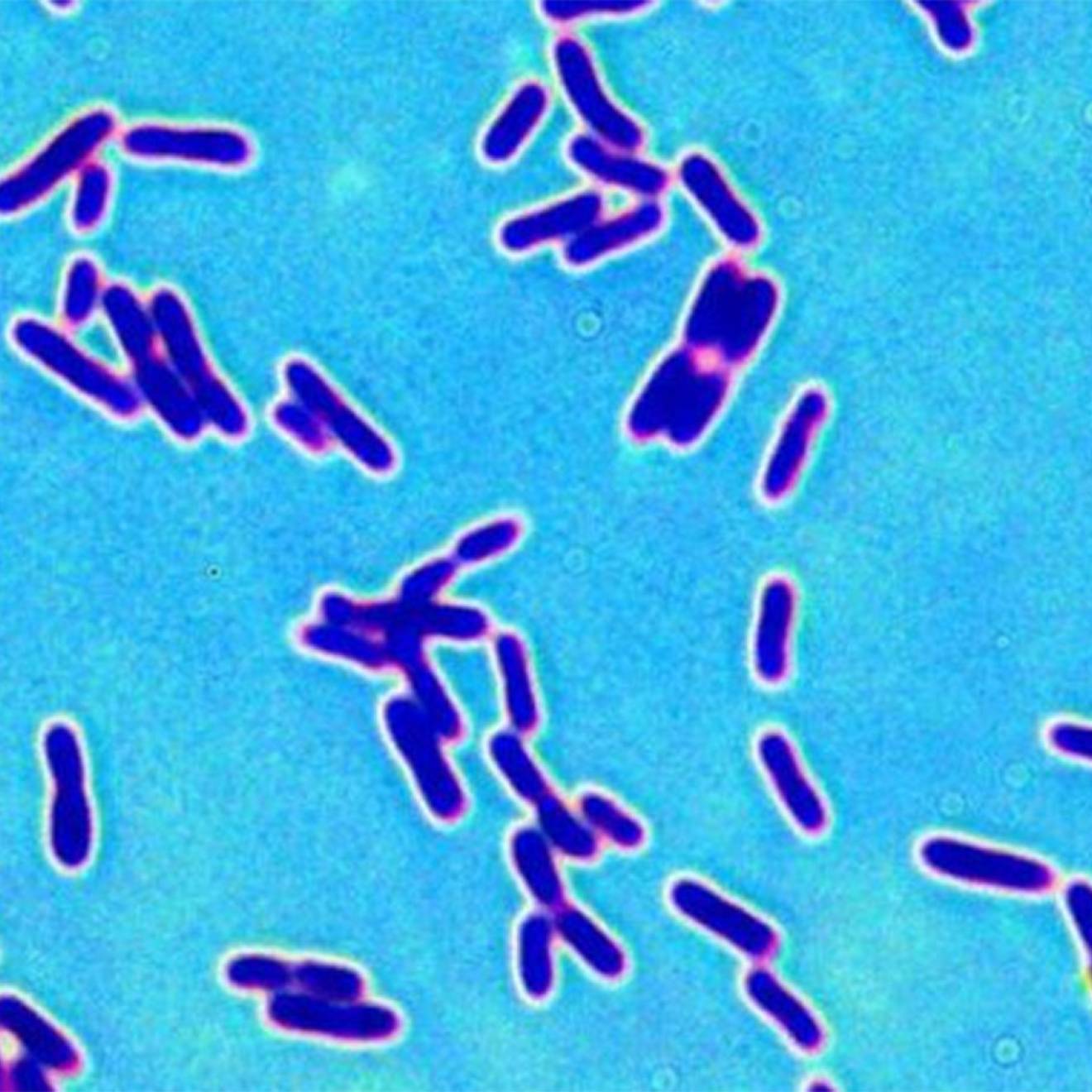

Credit: Kathy Keatley Garvey, UC Davis

Positive buzz

The situation with bees has been a serious concern for some time, but not all news is dire. Winter honeybee colony losses have been on the decline across the United States, and for the past two years the colony loss rate was well below the 9-year average. Another recent study from researchers at UC San Diego found that the Africanized honeybee range in California has been expanding northward nearly to Sacramento, and wild populations are helping crop pollination.

“The general public is increasingly aware of the issues facing pollinators and they want to help,” said Niño. The easiest thing to do, she says, is to grow forage plants for bees.

Backyard beekeeping, which has enjoyed a surge of interest in recent years, may be another source of hope for California’s bees — assuming novice beekeepers are properly caring for their hives. To help, UC Davis is offering beginning beekeeping classes in the fall to prepare new beekeepers for success in the spring.