Alison Hewitt, UCLA

In a study exploring racial bias and how people use their mind’s-eye image of an imagined person’s size to represent someone as either threatening or high-status, UCLA researchers found that people envisioned men with stereotypically black names as bigger and more violent.

The study, published today (Oct. 7) in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior, sought to understand how the human brain’s mechanism for interpreting social status evolved from the same mental systems that our early ancestors originally used to process threats. In a series of studies involving more than 1,500 people, the researchers found that an unknown black male is conceived of similarly to an unknown white male who has been convicted of assault.

“I’ve never been so disgusted by my own data,” said lead author Colin Holbrook, a research scientist in the anthropology department in the UCLA College. “The amount that our study participants assumed based only on a name was remarkable. A character with a black-sounding name was assumed to be physically larger, more prone to aggression, and lower in status than a character with a white-sounding name.”

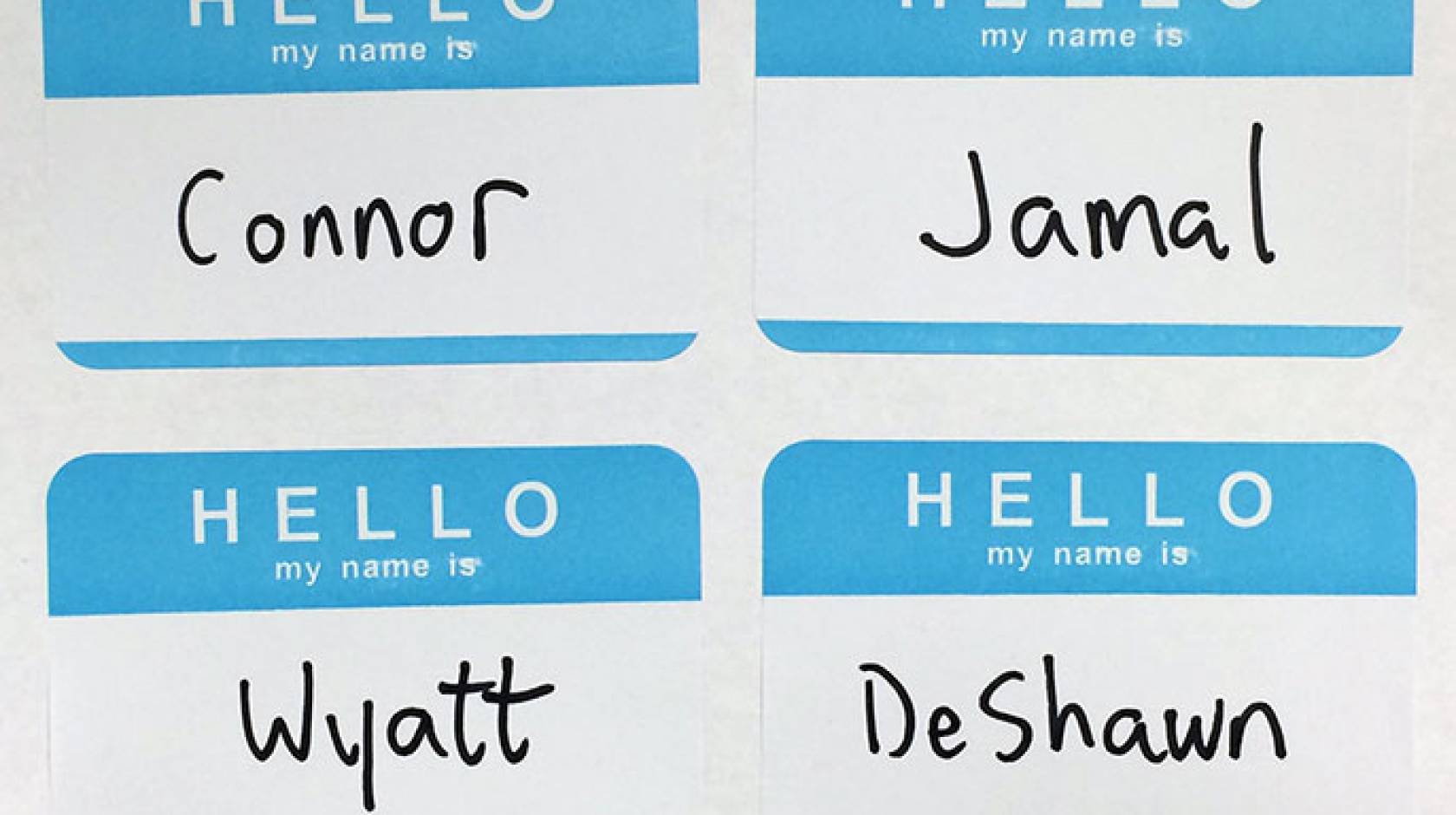

Jamal vs. Connor

During one version of the study, the mostly white participants, aged 18 to mid-70s, from all over the United States and self-identifying as slightly left of center politically, read one of two nearly identical vignettes. One featured a man named Jamal, DeShawn or Darnell, and the other featured Connor, Wyatt or Garrett — monikers selected based on prior research into names most commonly associated with various ethnic groups.

Study vignette:

[NAME] woke up Saturday morning and began his day by brushing his teeth and taking a shower. After eating breakfast, [NAME] watched TV for a while and talked on the phone. Then [NAME] went to a nearby store and bought some groceries. Once he had gotten home, [NAME] received a text message from a friend inviting him to go out later. That night, [NAME] went out to meet his friends at a bar. As he entered the crowded bar, he brushed against the shoulder of a man walking the other direction. The man turned, glared at [NAME], and angrily said “Watch where you’re going, a--hole!”

In another version of the study, participants again read a vignette with one of the two types of names. A control group read the original “neutral” vignette. The other groups read the same vignette with one of two additions: a “successful” scenario in which the character was a college graduate and successful business owner, or a “threatening” scenario in which the character had been convicted of aggravated assault. In all versions of the study, participants were asked their intuitive impression of the character’s height, build, status, aggressiveness and other factors.

“In the ‘successful’ scenario, the white and black characters are similarly perceived,” Holbrook said. “And when the character is convicted of assault, they again have similar outcomes, no matter their name. But people imagine the neutral black character as similar in size to the white criminal character, and we know that this shift in size is a proxy for how violent and aggressive they implicitly perceive the person to be. It’s quite disturbing.”

Participants rated each character on height, muscularity and size, and the composite score for all three characteristics was statistically equivalent for the “black neutral” character and the “white criminal” character.

Assumptions of socio-economic status

Not only did participants envision the characters with black-sounding names as larger, even though the actual average height of black and white men in the United States is the same, but the researchers also found that size and status were linked in opposite ways depending on the assumed race of the characters. The larger the participants imagined the characters with “black”-sounding names, the lower they envisioned their financial success, social influence and respect in their community. Conversely, the larger they pictured those with “white”-sounding names, the greater they envisioned their status, said co-author and UCLA anthropology professor Daniel Fessler, director of the UCLA Center for Behavior, Evolution and Culture.

“In essence, the brain’s representational system has a toggle switch, such that size can be used to represent either threat or status,” Fessler said. “However, apparently because stereotypes of black men as dangerous are deeply entrenched, it is very difficult for our participants to flip this switch when thinking about black men. For study participants evaluating black protagonists, dangerous equals big and big equals dangerous, period.”

The researchers have long been interested in what influences people’s perceptions of how physically formidable another person is. Their previous research found that marching in unisonmade men view opponents as smaller and less intimidating, and that opponents with a weaponwere perceived as larger and stronger.

In their latest research paper, the authors also evaluated the effect of traditionally Hispanic names versus traditionally East Asian names. Study participants rated characters named “Jorge” or “Juan,” for example, as larger, more violent and lower in status than characters named “Chen” or “Hikaru.”

Correlating race to behavior

The researchers chose to study how race played into people’s conceptions of size, status and aggressiveness after several highly controversial incidents nationwide in which unarmed black men were killed by authority figures or police. The killings raised serious questions of racism and sparked the “Black Lives Matter” movement.

“I think our study participants, who were overall on the liberal end of the spectrum, would be dismayed to know this about themselves,” Holbrook said. “This study shows that, even among people who understand that racism is still very real, it’s important for them to acknowledge the possibility that they have not only prejudicial but really inaccurate stereotypes in their heads.”

The study’s third co-author is Fessler’s former graduate student Carlos Navarrete, now an associate professor at Michigan State University. The study is part of a larger project funded by a grant from the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research to understand how people make decisions in situations where violent conflict is a possibility.