Nicole Freeling, UC Newsroom

Rewriting evolutionary history with cyborg bacteria, planetary dynamics around cramped exoplanet star systems: These may sound like the kinds of esoteric topics that would be hard for the average person to comprehend.

But over the last several weeks, UC master's and doctoral students have been at work breaking down such heady material into bite-sized explanations that are understandable and engaging for a general audience.

Across UC campuses, grad students have been pacing the halls, practicing their pitches and consulting their stopwatches in preparation for Grad Slam, a contest for communicating research. Each campus will crown a winner – the student who is best able to boil down years of study and explain it in three minutes, TED style.

Those 10 finalists will then square off April 22 at the UC Grad Slam finale, hosted at the LinkedIn offices in San Francisco. The winners will share in $10,000 in prize money and get to take home the UC Grad Slam trophy – or “Slammy,” as it is affectionately known.

The contest is about more than prizes and bragging rights: It helps grad students build valuable skills in explaining the what and why of their research.

Credit: UCLA Graduate Division

Participants get training – such as one-on-one coaching sessions and theater workshops – to hone their skills in communication and public speaking.

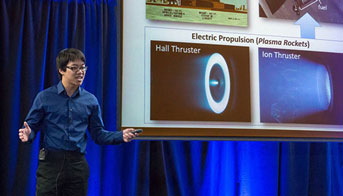

“When someone at a party would ask me what my research was all about, I was at a loss for words,” said UCLA aerospace engineering grad student Gary Li.

Li decided to sign up for the contest on the spur of the moment when he saw a message about it in his email. “I had no expectations,” he said. “I just wanted to improve my skills to explain to friends or future colleagues what my research was all about.”

He ended up taking home the campus trophy for his talk on engineering so-called plasma rockets, next-generation space craft technology that is less prone to breakdown during the long haul to Mars and beyond. (“There’s no AAA in space,” he quipped.)

A way to bring research to the public sphere

The contest shines a light on an often-overlooked force behind UC’s excellence in education and research: 26,000 academic Ph.D. students who are engaged in wide-ranging – and often game-changing – discovery in fields spanning hard sciences to humanities.

“When scientists and scholars are able to communicate their research without jargon, it helps them connect with colleagues outside their field, get fellowships and land career opportunities,” said UC President Janet Napolitano.

“But even more critically, it allows them to bring their expertise into the public sphere, where we all can benefit from their knowledge.”

Napolitano will emcee the final UC-wide Grad Slam contest, to be judged by a panel representing leaders from industry, media and government.

LinkedIn is co-hosting the event in their shiny new San Francisco digs as part of a daylong Workforce of the Future Summit, held in partnership with UC and the Bay Area Council.

The day will also feature a panel discussion by UC, government and industry leaders on the role of the research university in cultivating the landscape of jobs and opportunity.

Honing in on why their research matters

More than 500 grad students across UC campuses participated in the contest this year.

For many, the contest offers the chance not just to earn prizes and glory, but the opportunity to get beyond the day-to-day grind to see their work in a broader context.

Credit: Robert Durrell

That, participants say, is well worth the dozens of hours spent writing drafts of their talk, trimming it and trimming again, and practicing it in front of friends and strangers.

“The point of graduate school is to become an expert in one very specific area,” said UC San Francisco grad student Meera Shenoy.

She is in her third year of doctoral research, studying the role microbes play in patients’ likelihood of surviving HIV-related pneumonia. “You go to conferences where everyone’s an expert on the same narrow subject. It’s easy to lose sight of the bigger significance.”

At first, she said, it was hard to let go of details gleaned over years of hard work and research.

But when those were stripped away, she said, “Grad Slam helped me remember what got me excited about this research in the first place. That’s a perspective I’ll be able to carry forward as I continue on with this research. ”

To get his pitch down, Li practiced in front of a mirror and tested his talk on his roommate, his lab partners, and virtually anyone else who would listen.

He attended a small group coaching session to improve his public speaking, part of the training that is available to all students who sign up to participate in the contest.

When he talks about that research at parties now, he gets the kind of reaction you might expect for someone building a technology that might enable man to travel beyond the stars.

“I don’t see looks of confusion. I see looks of interest and appreciation. And people ask follow up questions,” he said.

“If you speak in jargon, people don’t ask questions. They don’t have any idea what you’re talking about.”