Laura Perry, UCLA

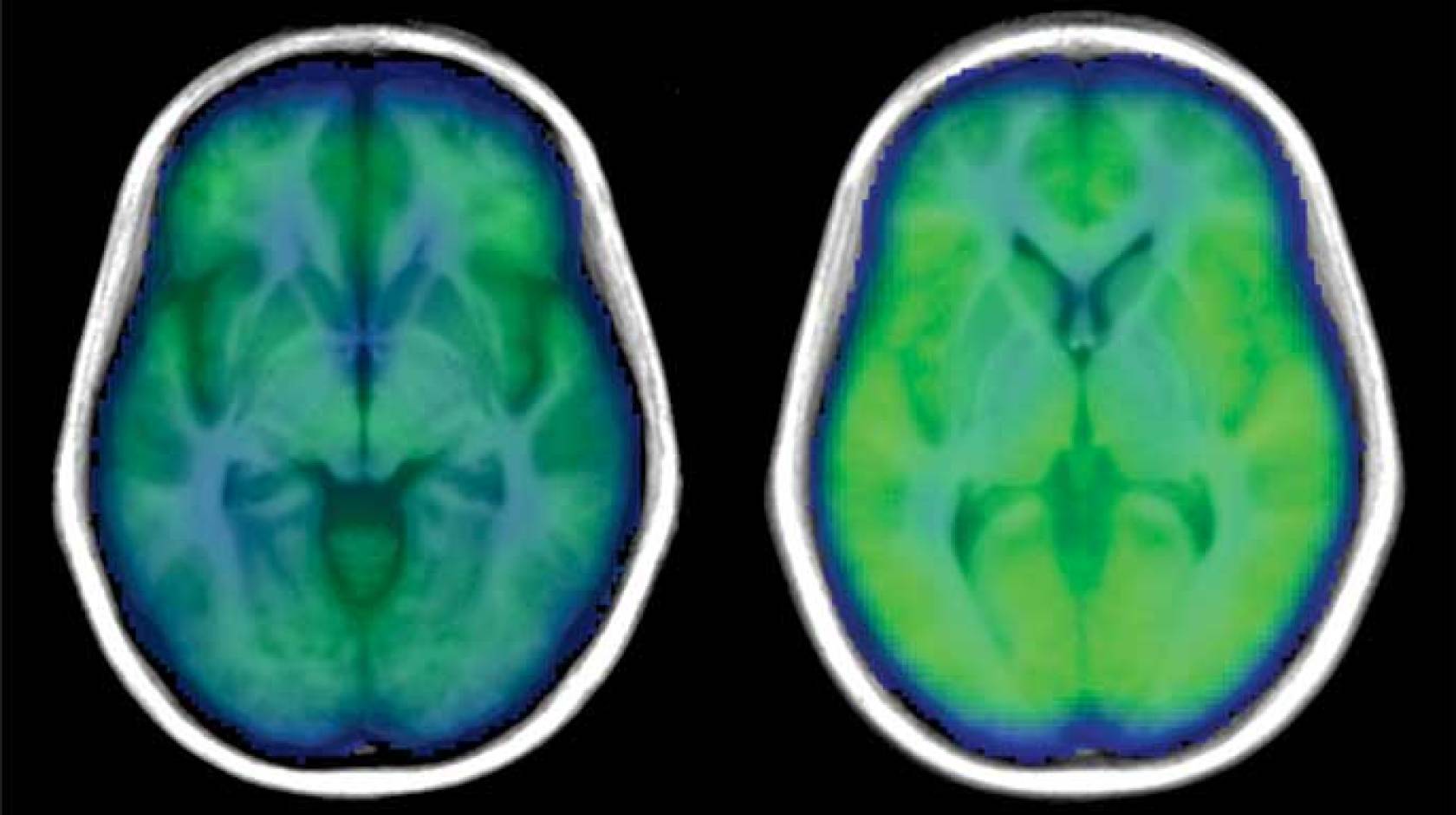

Employing a measure rarely used in sleep apnea studies, researchers at the UCLA School of Nursing have uncovered evidence of what may be damaging the brain in people with the sleep disorder — weaker brain blood flow.

In the study, published Aug. 28 in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE, researchers measured blood flow in the brain using a non-invasive MRI procedure: the global blood volume and oxygen dependent (BOLD) signal. This method is usually used to observe brain activity. Because previous research showed that poor regulation of blood in the brain might be a problem for people with sleep apnea, the researchers used the whole-brain BOLD signal to look at blood flow in individuals with and without obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

“We know there is injury to the brain from sleep apnea, and we also know that the heart has problems pumping blood to the body, and potentially also to the brain,” said Paul Macey, associate dean for Information Technology and Innovations at the UCLA School of Nursing and lead researcher for the study. “By using this method, we were able to show changes in the amount of oxygenated blood across the whole brain, which could be one cause of the damage we see in people with sleep apnea.”

Obstructive sleep apnea is a serious disorder that occurs when a person's breathing is repeatedly interrupted during sleep, hundreds of times a night. Each time breathing stops, the oxygen level in the blood drops, which damages many cells in the body. If left untreated, it can lead to high blood pressure, stroke, heart failure, diabetes, depression and other serious health problems. Approximately 10 percent of adults struggle with obstructive sleep apnea, which is accompanied by symptoms of brain dysfunction, including extreme daytime sleepiness, depression and anxiety, and memory problems.

In this study, men and women — both with and without obstructive sleep apnea had their BOLD signals measured during three physical tasks while they were awake:

- The Valsalva maneuver: participants forcefully breathe out through a very small tube, which raises the pressure in the chest.

- A hand-grip challenge: participants squeeze hard with their hand.

- A cold pressor challenge: A participants’s right foot is put in icy water for a minute.

“When we looked at the results, we didn’t see much difference between the participants with and without OSA in the Valsalva maneuver,” said Macey. “But for the hand-grip and cold-pressor challenges, people with OSA saw a much weaker brain blood flow response.”

The researchers believe that the reason there were differences in the sleep apnea patients during the hand-grip and cold pressor challenge was because the signals from the nerves in the arms and legs had to be processed through the high brain areas controlling sensation and muscle movement, which was slower due to the brain injury. On the other hand, the changes from the Valsalva are mainly driven by blood pressure signaling in the chest, and do not need the sensory or muscle-controlling parts of the brain.

“This study brings us closer to understanding what causes the problems in the brain of people with sleep apnea,” concluded Macey.

The study also found the problem is greater in women with sleep apnea, which may explain the worse apnea-related outcomes in females than males. Studies recently published by the UCLA School of Nursing have shown that brain injury from sleep apnea is much worse in women than men.

The researchers are now looking at whether treatment for obstructive sleep apnea can reverse the damaging effects.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research. Other authors of the study were Rajesh Kumar, Jennifer Ogren, Mary Woo and Ronald Harper, all of UCLA.