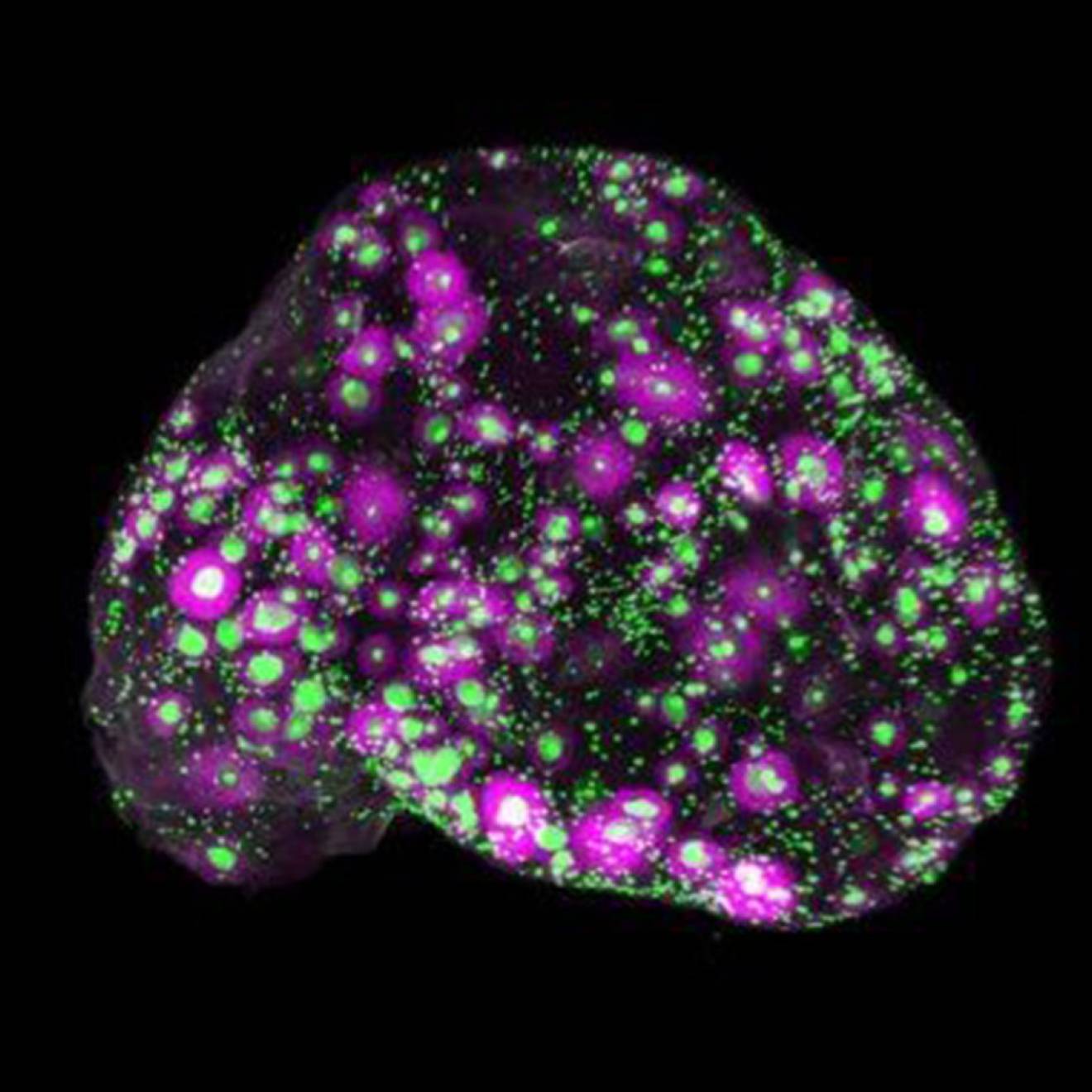

Annie Reisewitz, UC San Diego

A swarm of nearly 200 small earthquakes that shook Southern California residents in the Salton Sea area last week raised concerns they might trigger a larger earthquake on the southern San Andreas Fault. At the same time, scientists from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego and the Nevada Seismological Laboratory at the University of Nevada, Reno published their recent discovery of a potentially significant fault that lies along the eastern edge of the Salton Sea.

The presence of the newly mapped Salton Trough Fault, which runs parallel to the San Andreas Fault, could impact current seismic hazard models in the earthquake-prone region that includes the greater Los Angeles area. Mapping of earthquake faults provides important information for earthquake rupture and ground-shaking models, which helps protect lives and reduce property loss from these natural hazards.

The National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded study appears in the Oct. 2016 issue of the journal Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

“To aid in accurately assessing seismic hazard and reducing risk in a tectonically active region, it is crucial to correctly identify and locate faults before earthquakes happen,” said Valerie Sahakian, a Scripps alumna, and lead author of the study.

The research team used a suite of instruments, including multi-channel seismic data, ocean-bottom seismometers, and light detection and ranging, or lidar, to precisely map the deformation within the various sediment layers in and around the sea’s bottom. They imaged the newly identified strike-slip fault within the Salton Sea, just west of the San Andreas Fault.

“The location of the fault in the eastern Salton Sea has made imaging it difficult and there is no associated small seismic events, which is why the fault was not detected earlier,” said Scripps geologist Neal Driscoll, the lead principal investigator of the NSF-funded project, and coauthor of the study. “We employed marine seismic equipment to define the deformation patterns beneath the sea that constrained the location of the fault.”

Helping San Andreas bear its burden

Recent studies have revealed that the region has experienced magnitude 7 earthquakes roughly every 175 to 200 years for the last thousand years. A major rupture on the southern portion of the San Andreas Fault has not occurred in the last 300 years.

“The extended nature of time since the most recent earthquake on the Southern San Andreas has been puzzling to the earth sciences community,” said Nevada State Seismologist Graham Kent, a coauthor of the study and former Scripps researcher. “Based on the deformation patterns, this new fault has accommodated some of the strain from the larger San Andreas system, so without having a record of past earthquakes from this new fault, it’s really difficult to determine whether this fault interacts with the southern San Andreas Fault at depth or in time.”

The findings provide much-needed information on the intricate structure of earthquake faults beneath the sea and what role it may play in the earthquake cycle along the southern end of the San Andreas Fault. Further research will help provide information into how the newly identified fault interacts with the Southern San Andreas Fault, which may offer new insights into the more than 300-year period since the most recent earthquake.

“We need further studies to better determine the location and character of this fault, as well as the hazard posed by this structure,” said Sahakian, currently a postdoctoral fellow at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Earthquake Science Center. “The patterns of deformation beneath the sea suggest that the newly identified fault has been long-lived and it is important to understand its relationship to the other fault systems in this geologically complicated region.”

Scripps researcher Alistair Harding and Nevada Seismological Laboratory seismologist and outreach specialist Annie Kell also contributed to the study.