Kate Rix, UC Newsroom

A demonstration project aimed at improving patient care for people with HIV and AIDS has reduced the number of hospital re-admissions at one Bay Area hospital by 44 percent.

The new approach — jointly funded by the California HIV/AIDS Research Program (CHRP) at the University of California, the Alameda County Health Care Services Agency, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Alameda Health System — puts primary care physicians at the helm of an integrated care team that includes social workers, psychologists and medical specialists.

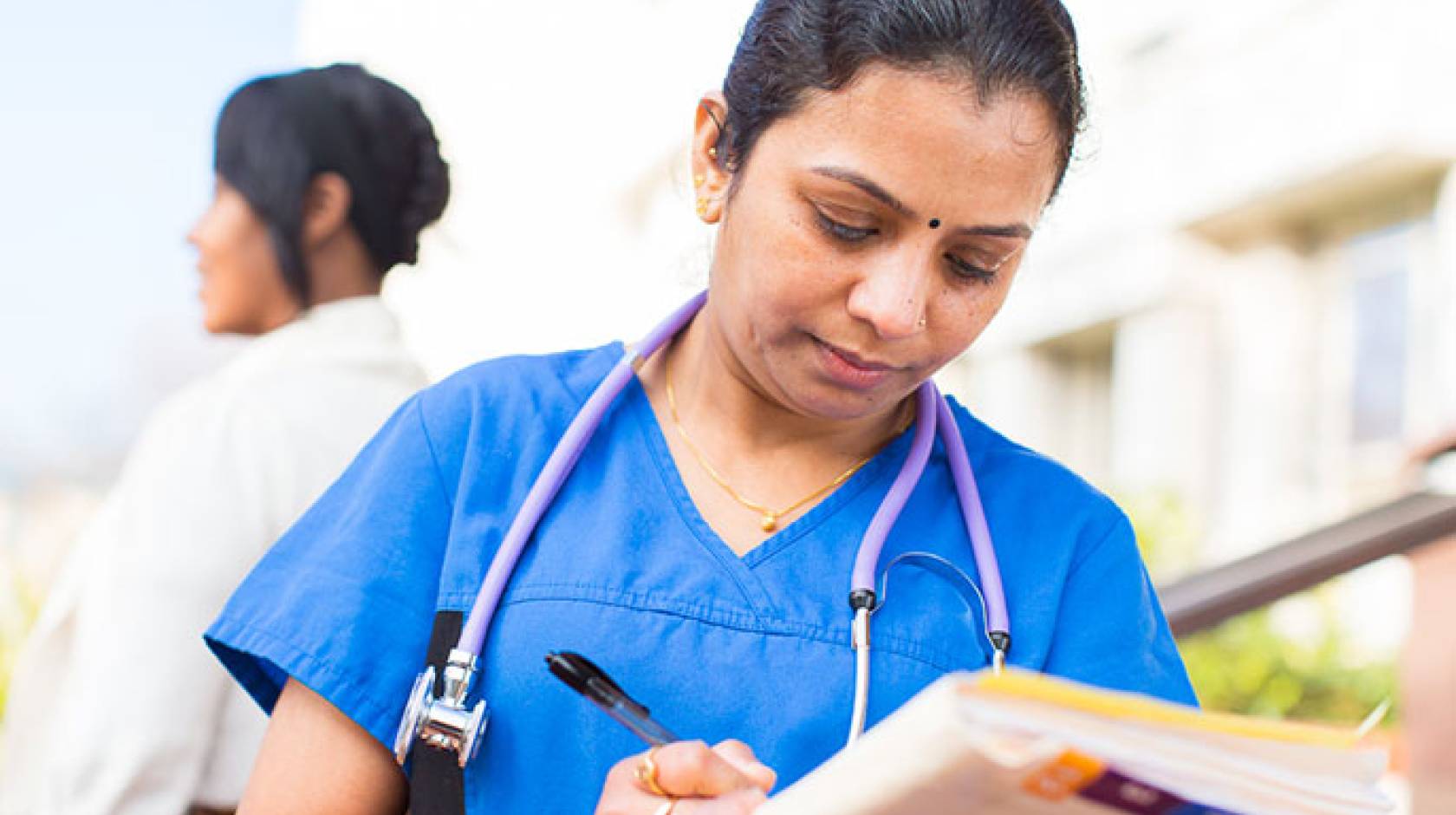

These collaborative teams form virtual "patient-centered medical homes" that work together to ensure that patients come to appointments, take their medications and get the care they need.

“The HIV epidemic has had a history of clients being advocates for their own care,” said John Mortimer, CHRP health policy and health services research program officer. “Our goal is to make medical care even more client-centered to help improve patient outcomes.”

Promising results

Early results are promising. Highland Hospital in Oakland looked at how many patients were re-admitted to the hospital in 2010 before the demonstration project started and compared it to re-hospitalizations during the pilot program.

As a result of Patient-Centered Medical Home care strategies, which included support for care transitions from hospital to outpatient care, the number of re-admissions fell significantly. Of 89 patients admitted in 2010 for HIV-related treatment, 35 were readmitted within a month. From October 2012 to September 2013, 63 patients were admitted, and only 14 of them were readmitted within 30 days.

“This shows that our system is working,” says Dr. Kathleen Clanon, medical director of the Health Program of Alameda County. “The supports are successfully in place outside the hospital.”

In addition to Oakland's Highland Hospital, four other community clinics are participating: the Tri-City Health Center in Fremont, Lifelong Medical Care in Berkeley, and La Clínica and Asian Health Services, both in Oakland.

“UC is happy to have supported this innovative and effective pilot research program,” said Dr. George Lemp, director of CHRP.

Meeting patient needs

Patients with HIV are especially in need of the kind of wrap-around services offered by the patient-centered medical homes project.

Only half of Californians with HIV consistently receive medical care. There are many reasons for this: lack of insurance, homelessness, lack of transportation and the stigma of the disease, among others.

And tracking every person who tests positive for the virus is like following a needle as it sifts through a haystack. This poses both individual and public health hazards.

HIV can only be suppressed — and rendered non-transmissible — if anti-retroviral medication is taken every day.

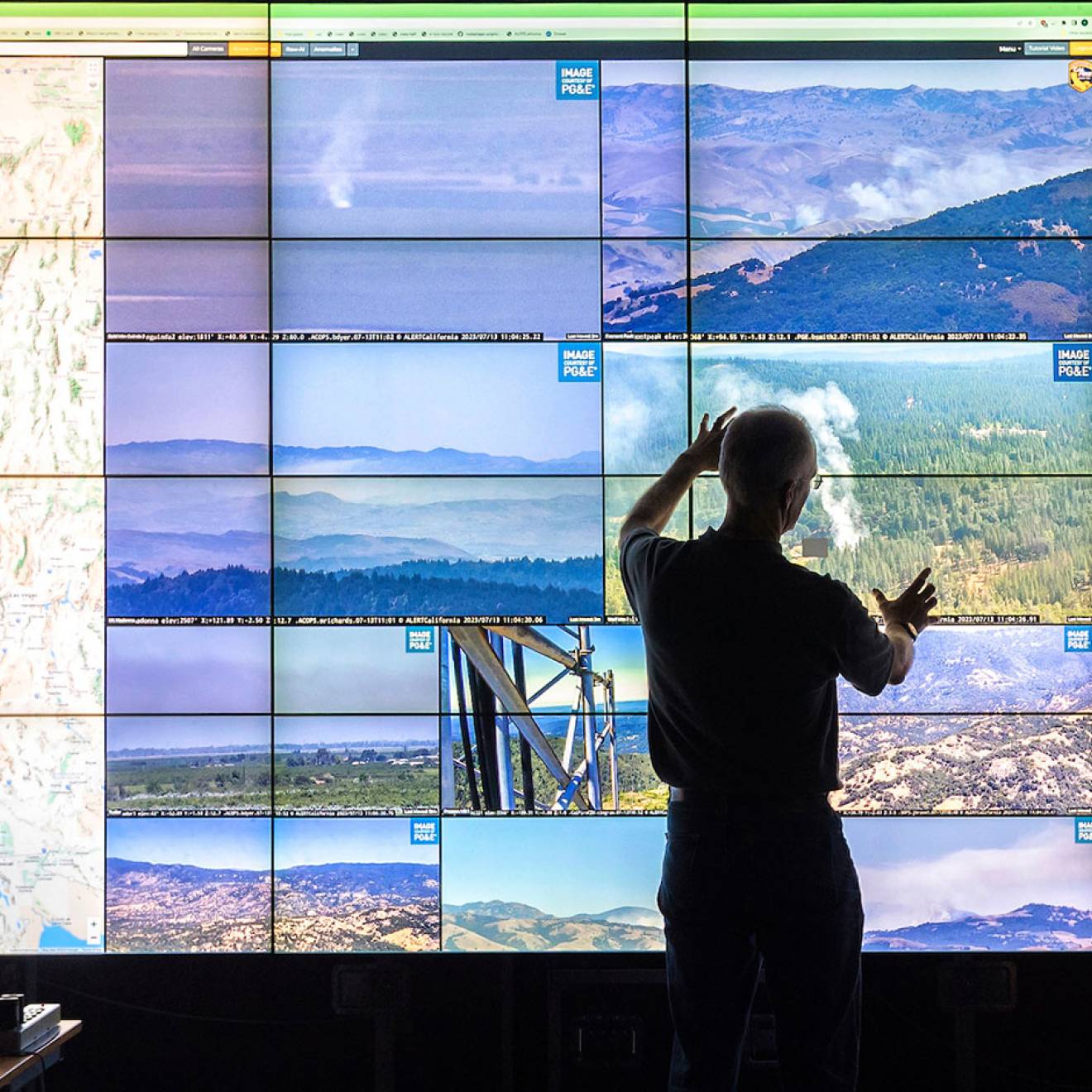

At the heart of the pilot project are tools that help clinics capture and centralize patient care information to better track individual needs. Highland uses the software system Lab Tracker and a customized database.

Centralized patient information

The tools, called registry reports and decision support sheets, give each physician’s team a detailed history: the last lab report, any missed appointments and unfilled prescriptions, but also, reports of depression or lack of adequate food and transportation.

Clinic staff work closely with patients, providing information about why tests are needed and reminding them, if need be, to get them done.

“I’m paying attention and want to be more involved,” said Monica Chadwick, a medical assistant at Highland’s Adult Immunology Clinic — a key implementer in the Highland pilot. “And I want the patient to be more involved as well.”

If a patient misses an appointment or does not refill a prescription, Chadwick is on the phone. And it’s not just a friendly reminder.

“A significant number of Monica’s calls involve cussing on the patient’s part and hang-ups,” Clanon says. “People are frightened we will reveal their diagnosis. They’re frightened in general. But we work to connect with people who don’t know what they need.”

It takes an average of 10 phone calls from the clinic before a person who has tested positive in Highland’s emergency department comes in for his or her first visit.

Time is a challenge. Clanon and Chadwick block out two appointment slots every month for a “team huddle” where they review their patient group and see what follow-ups are needed. That means other patients wait longer to see the doctor so that the team can track down people who haven’t come in.

Changing clinic culture

Clinic culture has also changed. Staff use the new tools to care for the patients they see regularly as well as the ones they do not: A telephone number on a computer screen for someone who has missed appointments is as important as the person sitting in the waiting room.

“I get a lot of support services here,” says one patient, who chose not to give his name. “The people here are very knowledgeable. They know about legal aid, transportation, and housing. They encourage you to take advantage of other services.”

The good news is that people with HIV are living long enough to make health and well-being a tangible goal.

“Because I’m working with patients who haven’t been seen in the clinic for a while, I tend to spend more time with people around the things that make accessing care hard for them,” Clanon says of the provider experience. “But I also get to work with them on what they need to do to stay well, like preventing pneumonia and going to the dentist. Bringing those two things together is the power of this program.”