As someone who suffered from chronic strep throat infections, Central Valley resident Vanessa Mora needed to go the doctor a lot as a kid. The problem was, all too often there wasn’t one.

In the rural agricultural community of Fowler, California, it could take weeks to get an appointment. Medical visits involved a long drive, a long wait, a huge medical bill, or all three. “Sometimes we’d go to the emergency room just so we could get seen,” she said.

Now, as a student in UC San Francisco’s San Joaquin Valley Program in Medical Education (SJV PRIME), Mora is training to be part of a new crop of homegrown physicians bringing care to one of the most medically-underserved regions of the state.

The program is looking to recruit medical students who want to return home to serve the area where they grew up — providing much-needed care to families in the region.

Among the fastest growing, poorest and least healthy regions of California, the San Joaquin Valley also has the lowest number of doctors, nurses and nurse practitioners per 100,000 people of any region in California. An added concern: Roughly 30 percent of this already stretched workforce is nearing the age of retirement.

Addressing a critical lack of access

The shortage of medical care providers constitutes its own health care emergency, said Dr. Katherine Flores, a family medicine physician in Fresno.

As a child, Flores grew up in a family of migrant workers, living in communal housing and traveling to follow the harvests.

“When I refer someone to a neurologist, it could take months to get an appointment,” Flores said.

Lack of access is just the start. Language, financial and cultural barriers also limit patients’ quality of care.

When it comes to the day-to-day realities of her patients, Flores said, some conventional medical advice simply isn’t workable.

Those in communal farmworker housing cannot easily quarantine if they get infected with COVID-19. Those without paid time off or their own transportation cannot easily get to a health care provider, be it for preventive or acute care.

“We don’t just need more doctors in this community. We need doctors who understand it. We need students who come from the Valley, who understand the culture of the Valley, who understand the challenges of poverty and the challenges of the community,” Flores said.

First-hand knowledge of the community's needs

The San Joaquin Valley PRIME program is trying to do just that.

Started in 2011 as a collaboration among UC Merced, UC Davis, UCSF Fresno and UC San Francisco, SJV PRIME has 45 currently enrolled students. More than 50 medical school graduates have completed the program, many of whom are now working in the Valley as residents or fully licensed physicians.

Along with having grown up in the community, many are native Spanish speakers, a huge benefit in a community where Spanish is often the primary language.

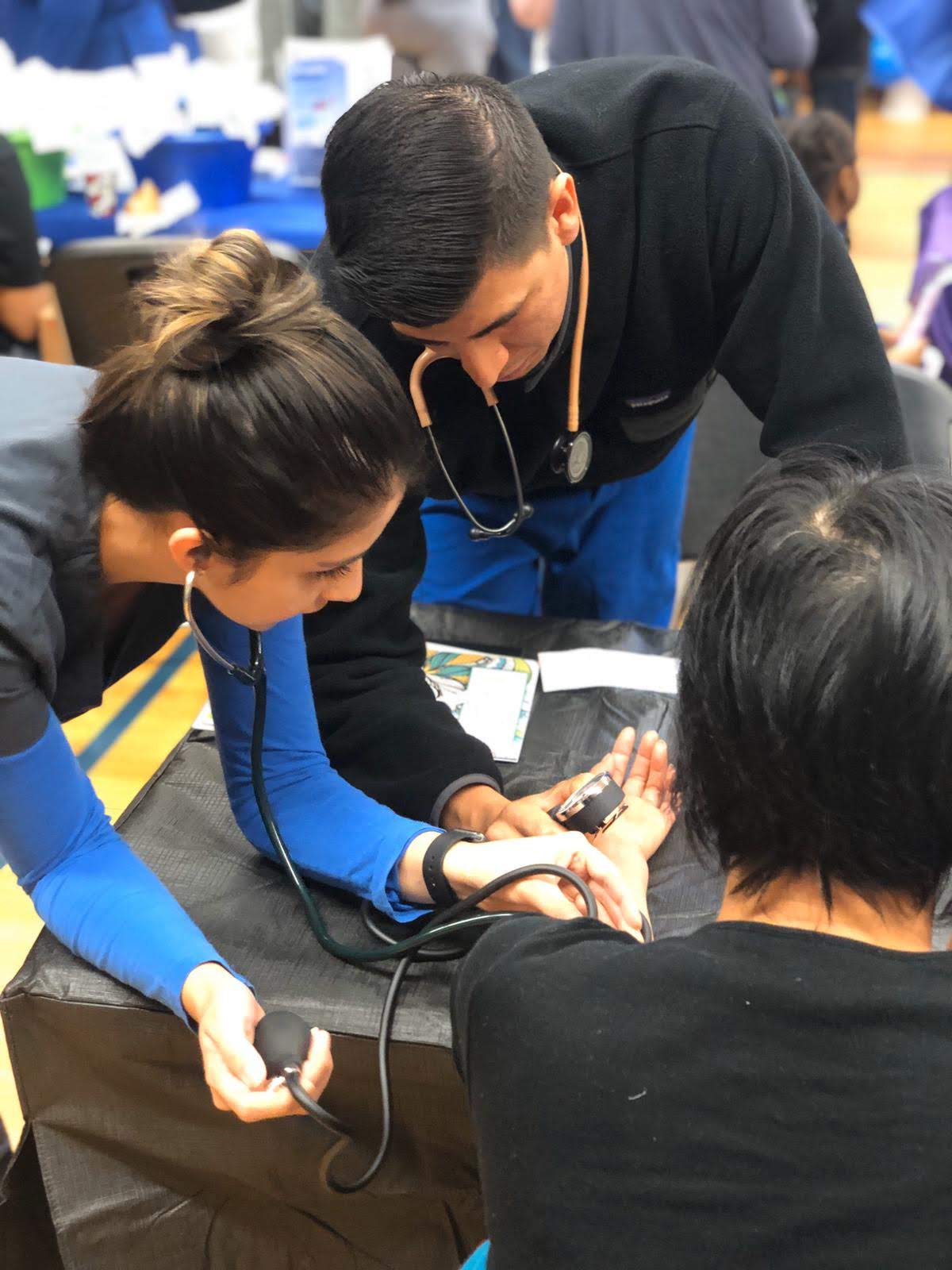

“Being from this community brings patients a lot of comfort. It helps them open up and discuss what’s on their mind,” Mora said.

Mora and a PRIME colleague take a patient's blood pressure at a Valley health clinic.

It also helps that Mora can relate to their concerns: Her own father, a welder, was often injured on the job and never saw the doctor, even when he lost part of his finger. Her mother ignored a dental issue until she ended up in the hospital with a life-threatening systemic infection.

“For people in my community, getting a diagnosis isn’t just about the treatment or what that means for their health,” Mora said. “It’s life-changing. Many are the head of their household. Their families rely on them to continue working and pushing through to make ends meet.”

Part of the PRIME training is learning about the network of social programs and community organizations that can help patients access services and meet basic needs.

Students learn about the social, environmental and economic determinants of health in the Valley. They receive training in public advocacy to push for reforms that could improve health outcomes for residents.

They also learn about the broad range of social services and community-based organizations that can help patients meet their basic needs.

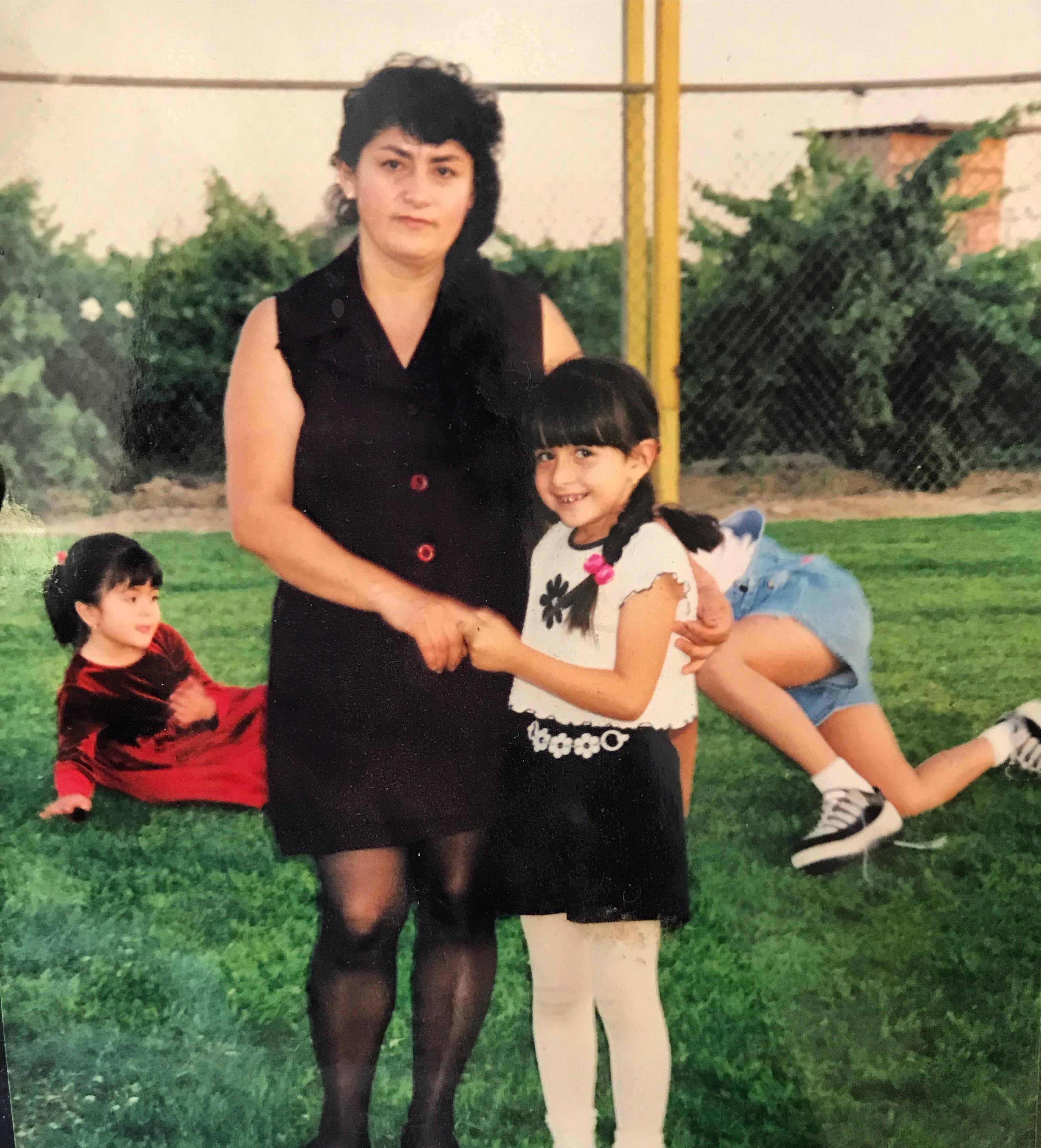

A young Vanessa Mora with her mom.

Finding strength in her own story

Growing up as one of four children of Mexican immigrants, Mora was always taught the value of hard work and education. She went to UC Santa Barbara to study biology.

While many of the classmates in her biology classes had their sights set on a career in medicine, “I felt medical school wasn’t in the cards for me. Not having mentors, I just didn’t think that was possible,” she said.

In her senior year, she met and began dating her now-partner, Rogelio Molina, who was also an aspiring physician. He convinced her that fear was not a reason to give up on her dream. While she worked full-time as a medical assistant, she applied to medical school twice without success.

Then she was accepted into the UCSF Postbaccalaureate Program. It helped her improve her MCAT scores, and most importantly, present herself as someone uniquely suited to help the community she wished to serve.

“I was trying to make myself into what I thought was the ideal pre-med student, when the reality is that wasn’t who I was,” she said.

Now she knows, especially in her community in the San Joaquin Valley, that she’s exactly the doctor her patients need.

“I have been able to find strength in my own story, and my ability to bring something important to the field.”