Roy Rivenburg, UC Irvine

If being sedentary is the new smoking, then UC Irvine’s nascent Exercise as Medicine class is the modern equivalent of the old surgeon general’s warning on cigarette packs.

Taught by James Hicks, professor of ecology & evolutionary biology, the course examines the hazards of physical inactivity and explores how exercise not only improves overall health but can even alter or reverse the trajectory of cancer and other diseases.

Hicks says he created the class – which debuted this spring with 85 biology students and turned away another 179 — to spread the gospel of walking, running and other forms of exertion.

“Because many biology majors go into medicine, I’m trying to make them converts who will tell their friends, parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents and patients that regular physical activity is like a fountain of youth,” he says.

For decades, science assumed that the gradual decline of physiological performance as people grow old was “a fixed slope, and by age 65 or 75, you’re supposed to be sitting in a rocking chair,” Hicks says. “We all die, but the slope can be altered.”

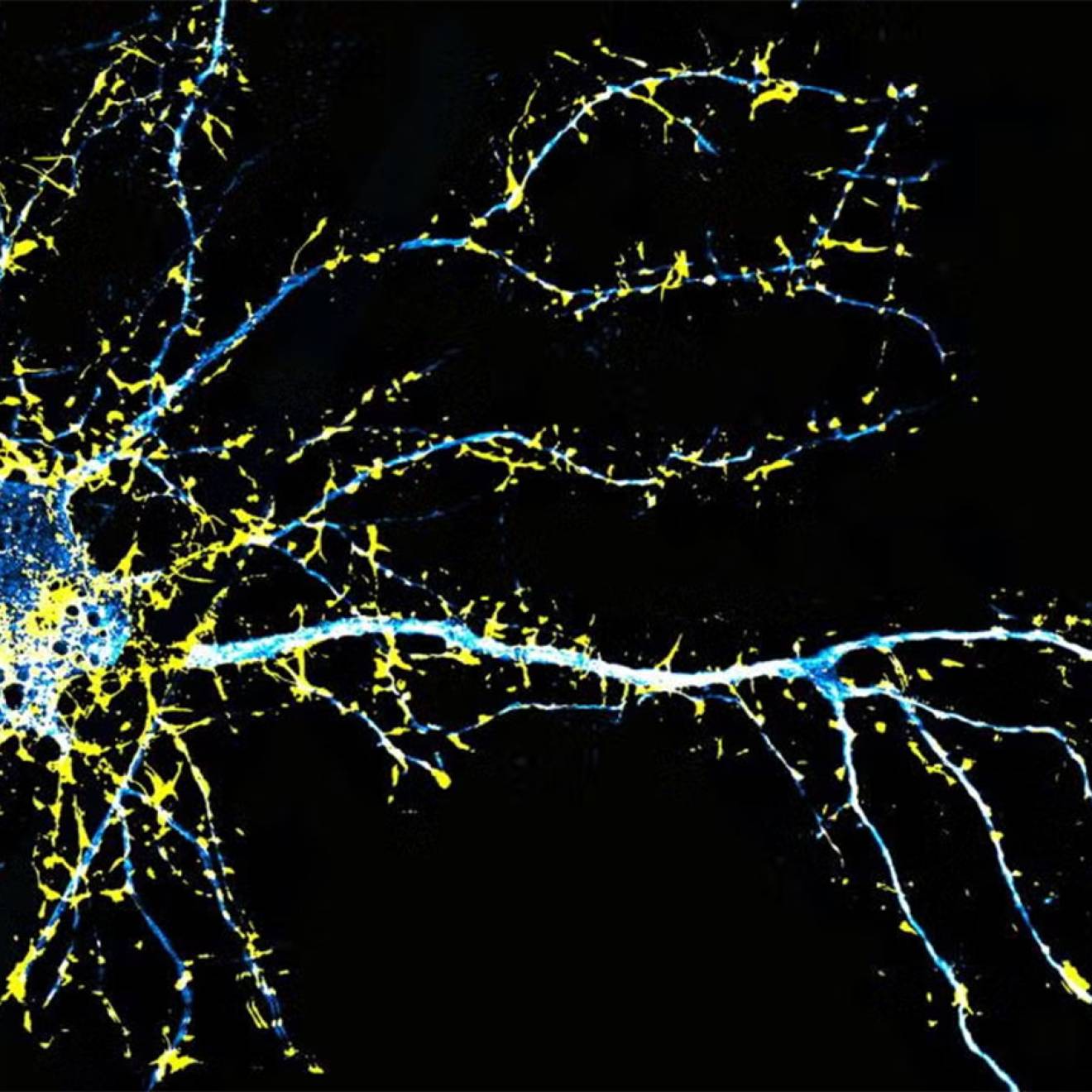

About 20 years ago, researchers discovered that intense movement causes muscles to release chemical compounds that boost health, immunity and longevity, he notes. It wasn’t an entirely new concept. Around 600 B.C., a physician in India prescribed daily exercise to his patients. And Hippocrates described walking as “man’s best medicine.”

Today there are reams of studies to back up these ancient suppositions. “I’ve collected gigabytes of literature on the connection between physical activity and health,” says Hicks, who previously directed UC Irvine’s Center for Exercise Medicine & Sport Sciences (now the Center for Integrative Movement Sciences).

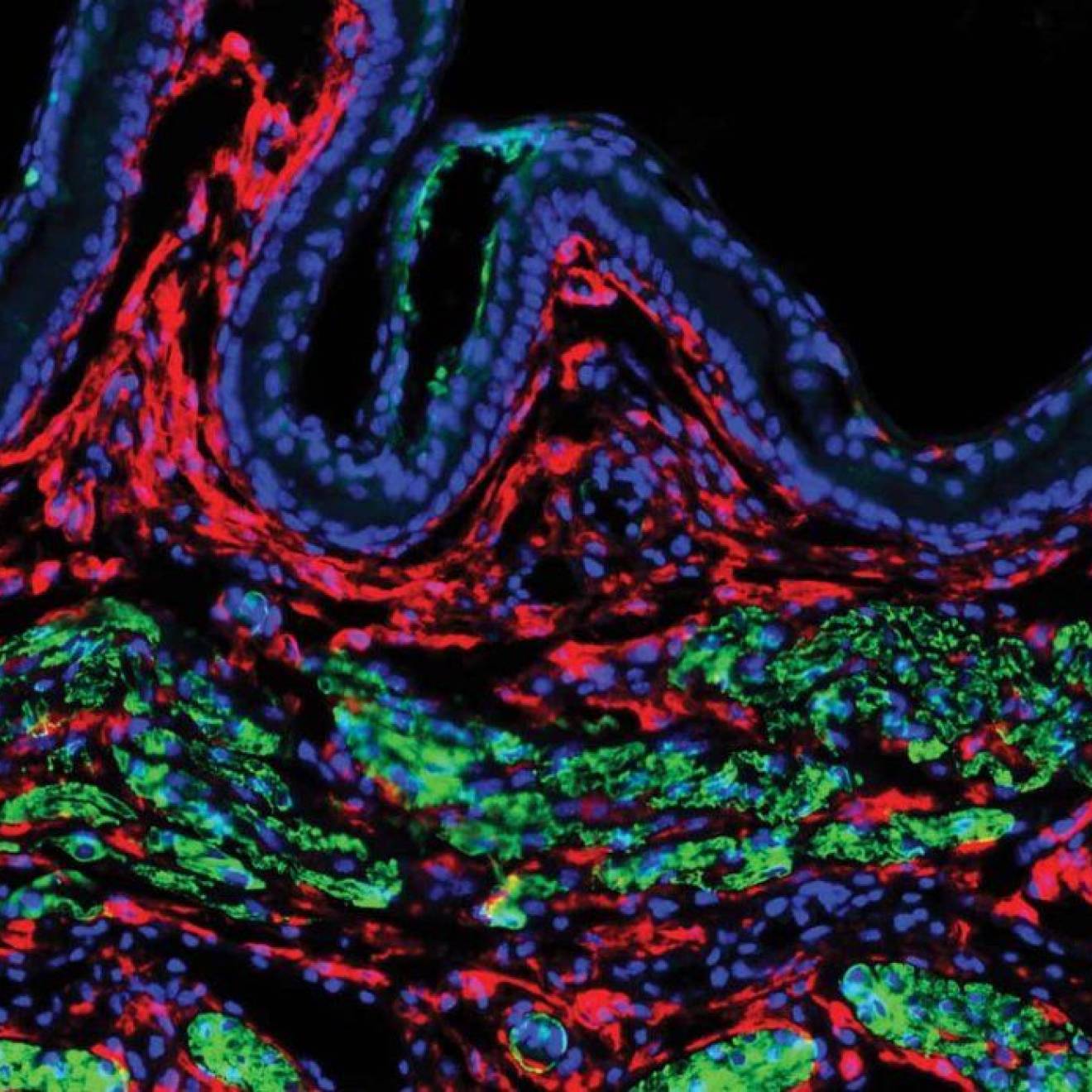

One of the subjects in his syllabus is the burgeoning field of exercise oncology. UCLA, UC San Francisco, Harvard University and New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center are among the medical institutions that recommend exercise as part of cancer treatment, he says, adding that specific activities can help with certain tumors. For example, breast cancer patients who walk briskly for three hours a week after receiving standard treatment have been reported to enjoy 32 percent better outcomes, a success rate few drugs can match, Hicks says.

Other lecture topics include exercise and diabetes, heart disease and brain health. Although there’s no lab component to the course, students log their activity levels and calculate how many calories they burn. At the beginning of the quarter, Hicks polled the class on how they spend their downtime and created a word cloud to display the results. The No. 1 leisure activity: watching YouTube.

Hicks hopes students will be less sedentary by the end of the course. One of the reasons the U.S. was hit so hard by COVID-19, he says, is that too many Americans are obese.

Known for his research on vertebrate hearts, Hicks, 67, practices what he teaches, bicycling 60 to 120 miles a week, walking to campus every day and taking stairs instead of elevators for climbs under five floors.

At the end of the Exercise as Medicine class, he plans to show a one-minute Canadian video that asks, “What will your last 10 years look like?” Using a split screen, it depicts the same actor in hauntingly parallel scenes, one version healthy and the other sickly. A key to finishing life on the healthy side, Hicks says, is staying physically fit: “We can age with vitality. It’s never too late to get started.”