Mike Peña, UC Santa Cruz

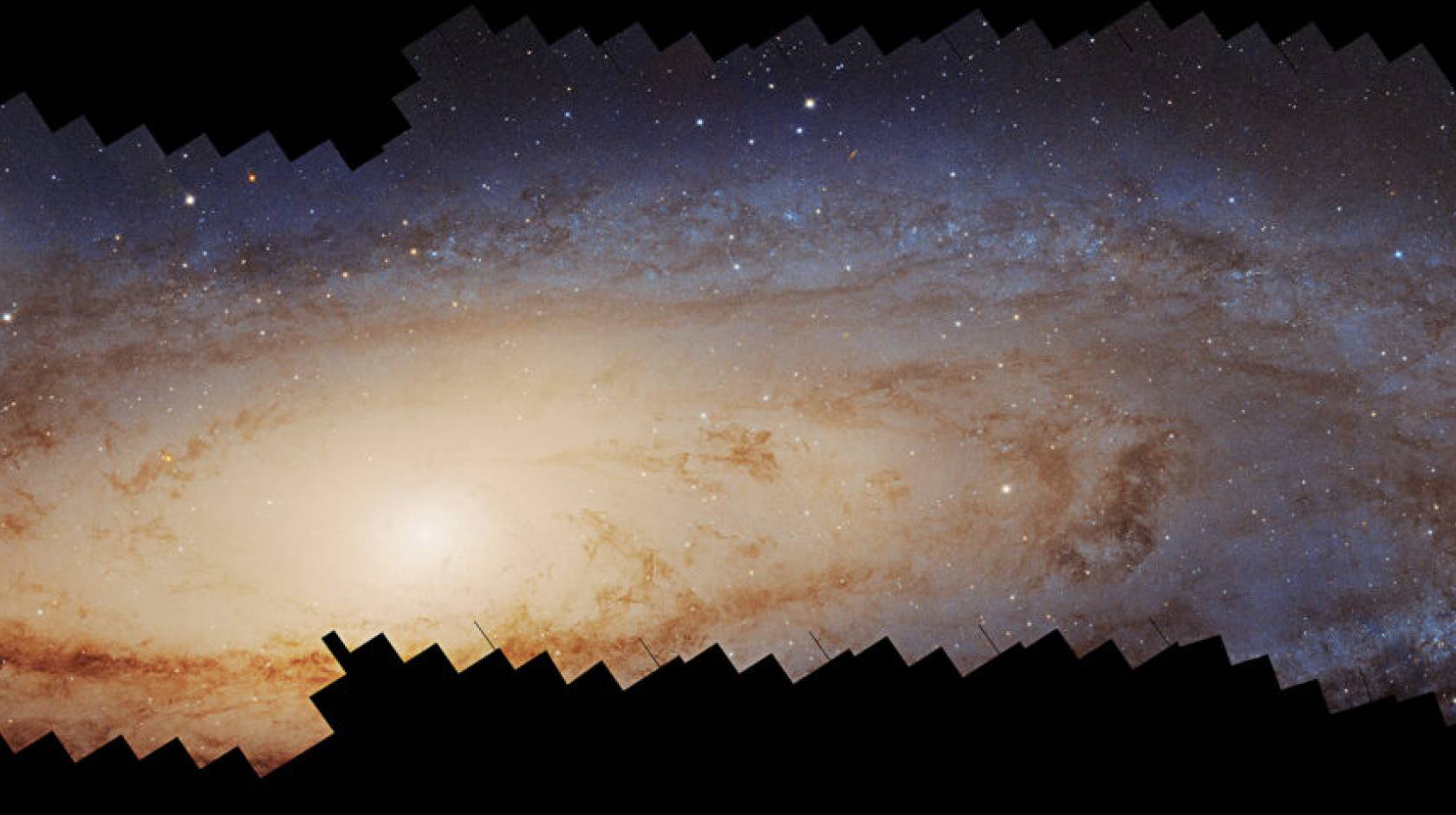

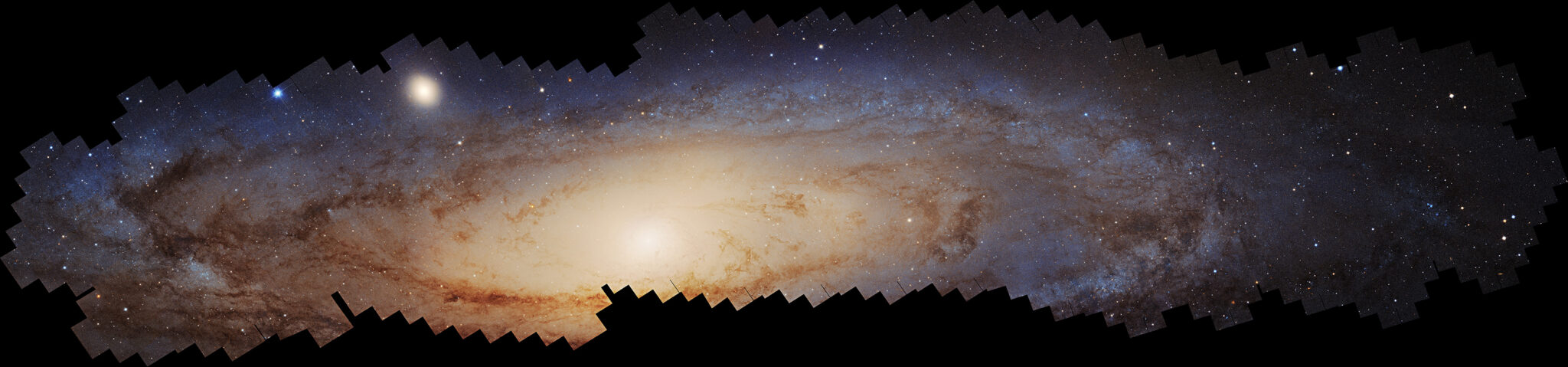

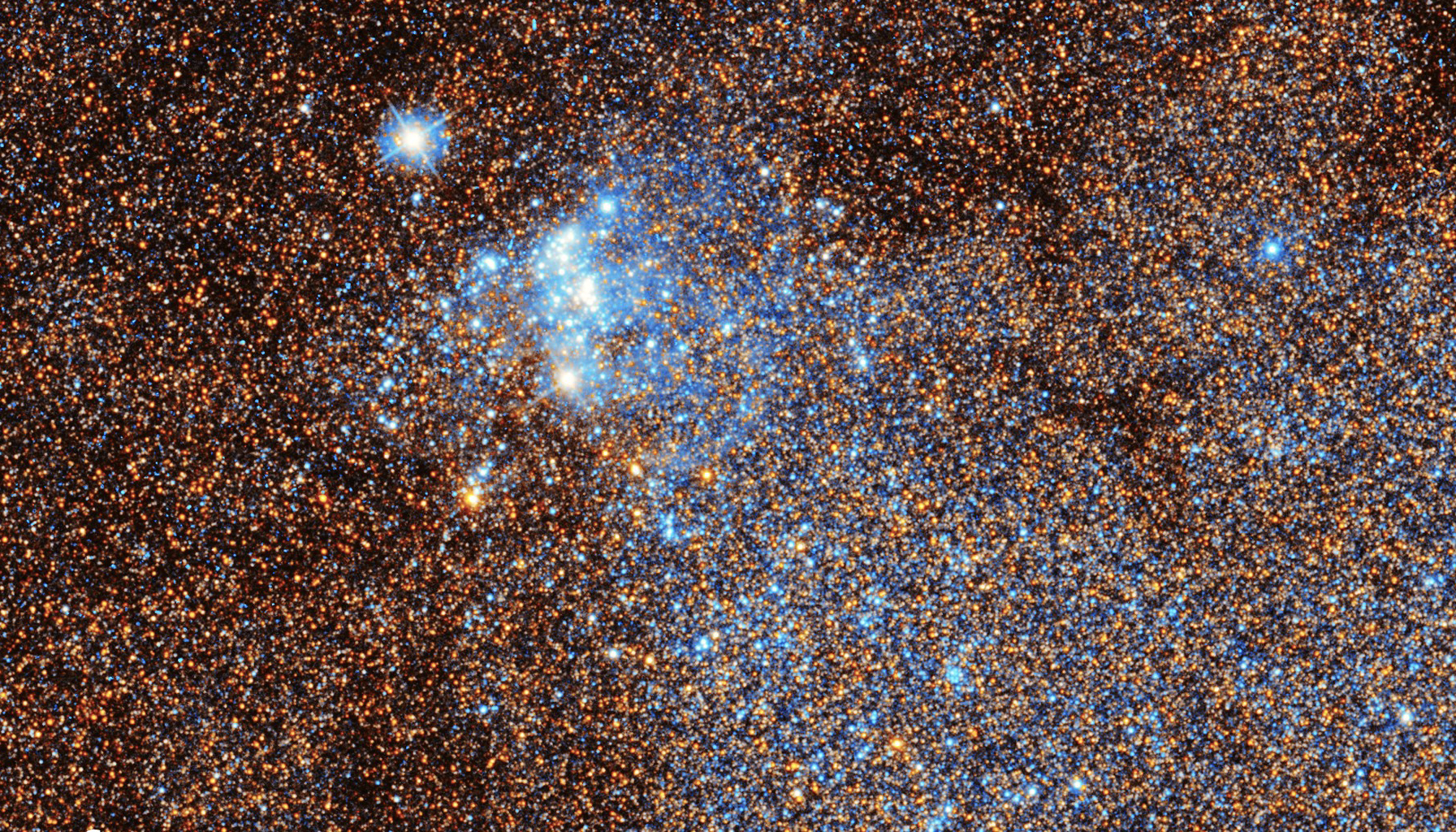

Astronomers are celebrating the completion of a 2.5-billion-pixel panoramic picture of the entire Andromeda galaxy. The team includes several UC Santa Cruz researchers who made significant contributions to the enormous photomosaic that combines some 600 snapshots taken by the Hubble Space Telescope over more than a decade and 1,000 orbits.

The astronomical panorama is a major accomplishment because Andromeda is the “closest” large galaxy to ours, at a distance of 2.5 million light years away — equal to the diameter of the Milky Way disk times 25. In addition to telling the turbulent history of the Andromeda galaxy, the mosaic will now allow astronomers to better understand our similarly spiraled Milky Way.

Without Andromeda as a proxy for spiral galaxies in the universe at large, astronomers would know much less about the structure and evolution of the Milky Way, according to the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI). “That's because we are embedded inside the Milky Way,” STScI stated in its January 16 announcement. “This is like trying to understand the layout of New York City by standing in the middle of Central Park.”

Professor Puragra “Raja” GuhaThakurta and Ph.D. student Douglas Grion Filho were among the astronomers from UC Santa Cruz who collaborated on the effort, which resulted in the largest mosaic of Hubble Space Telescope images ever created — resolving more than 200 million stars in the Andromeda galaxy.

The UC Santa Cruz team also studied the collection of stars that reside in the disk-shaped portion of Andromeda with the Deep Extragalactic Imaging Multi-Object Spectrograph (DEIMOS) at the W.M. Keck Observatory. As GuhaThakurta explained, Hubble’s images captured the number and variety of stars that make up Andromeda's disk, whereas the Keck DEIMOS spectra allowed his team to measure how fast each star is moving, as well as detail stellar characteristics such as surface temperature and gravity, chemical composition, age or evolutionary state.

“It’s analogous to viewing an aerial photo of a beach. However, this amazing data set allows us to zoom in to view and measure the properties of individual stars, which is somewhat like counting and measuring the properties of individual grains of sand on a beach,” he said. This data set is revolutionizing our understanding of how Milky Way-like galaxies form and evolve.”

Divide and capture

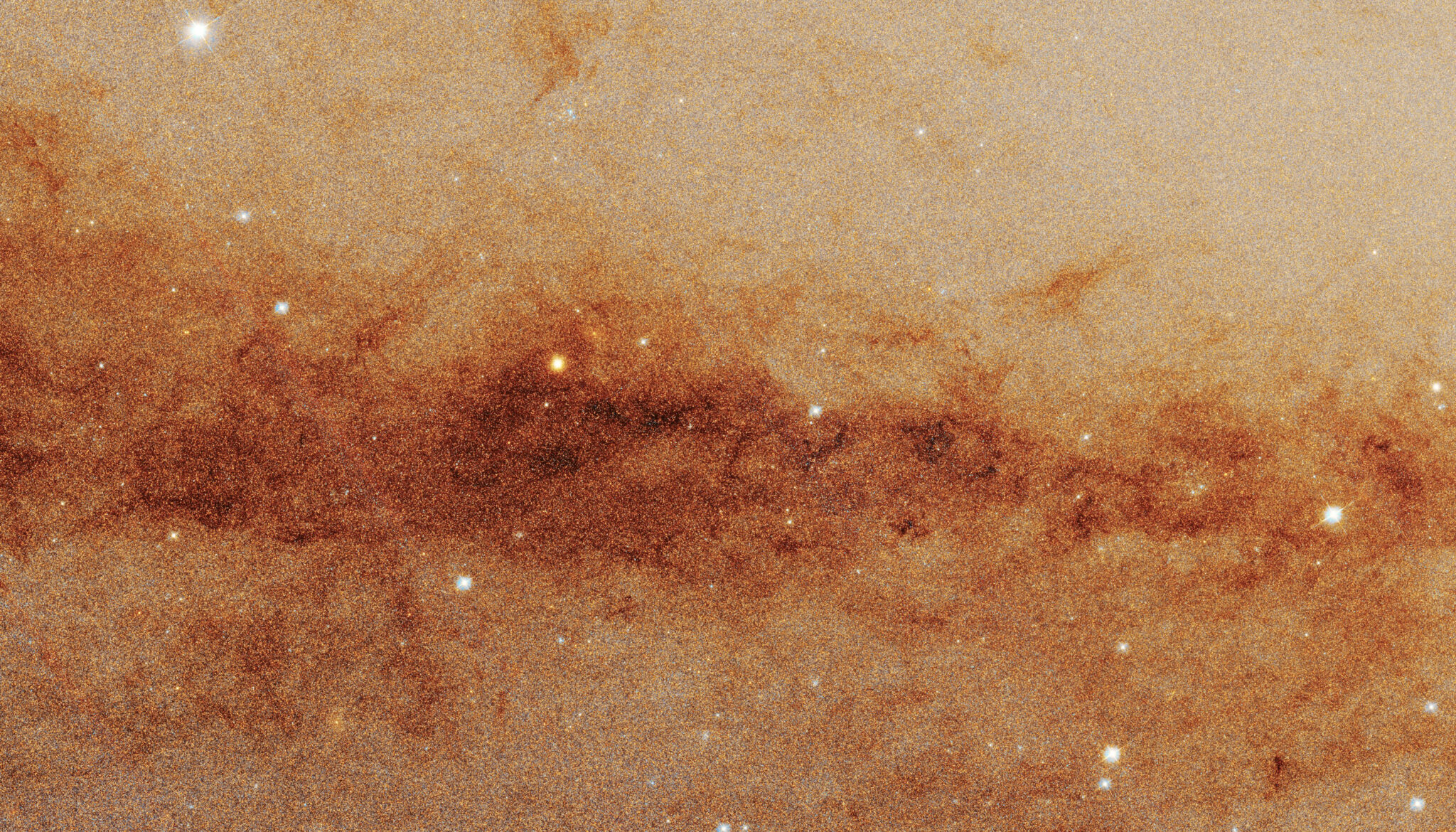

The panorama (above and at top) started with the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury (PHAT) program about a decade ago. Images were obtained at near-ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths using the Advanced Camera for Surveys and the Wide Field Camera 3 aboard Hubble to photograph the northern half of Andromeda.

This program was followed up by the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Southern Treasury (PHAST), recently published in the Astrophysical Journal and led by Zhuo Chen at the University of Washington, which added images of approximately 100 million stars in the southern half of Andromeda.

The combined programs collectively cover the entire disk of Andromeda, which is seen almost edge-on — tilted by 77 degrees relative to Earth's view. Hubble can only detect stars brighter than our Sun, enabling the telescope to capture just a fraction of Andromeda’s estimated total population of 1 trillion stars. The galaxy can be seen with the naked eye on a very clear autumn night as a faint cigar-shaped object roughly the apparent angular diameter of our Moon.

When Grion Filho joined UC Santa Cruz as a graduate student, GuhaThakurta’s group was in the midst of measuring velocities for a subsample of the stars present in PHAST. Over the past few years, Filho helped in the target selection of some of those stars, as well as performed some of the observations at Keck.

“In essence, we measure the line-of-sight velocity of the stars through their spectra and — with enough of these measurements — we can get a pretty good idea for how Andromeda as a whole is rotating and moving,” Grion Filho said.

In addition, this representative map of the line-of-sight velocities allowed the team to "turn the clock back," Filho explained. “It helps us understand the prior history of Andromeda — if it had any prior mergers, when these mergers occurred, and what effect they have had on the galaxy. Andromeda clearly has had a more active merger history than the Milky Way, and we can see that in the velocity plane quite clearly.”

A galactic ‘train wreck’

Though the Milky Way and Andromeda formed presumably around the same time many billions of years ago, observational evidence shows that they have very different evolutionary histories, despite growing up in the same cosmological neighborhood. Andromeda seems to be more highly populated with younger stars and unusual features like coherent streams of stars, say researchers. This implies it has a more active recent star-formation and interaction history than the Milky Way.

"Andromeda's a train wreck. It looks like it has been through some kind of event that caused it to form a lot of stars and then just shut down," said Daniel Weisz, an associate professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley. "This was probably due to a collision with another galaxy in the neighborhood."

A possible culprit is the compact satellite galaxy Messier 32, which resembles the stripped-down core of a once-spiral galaxy that may have interacted with Andromeda in the past. Computer simulations suggest that when a close encounter with another galaxy uses up all the available interstellar gas, star formation subsides.

"Andromeda looks like a transitional type of galaxy that's between a star-forming spiral and a sort of elliptical galaxy dominated by aging red stars," Weisz said. "We can tell it's got this big central bulge of older stars and a star-forming disk that's not as active as you might expect given the galaxy's mass."

Astronomers refer to the Andromeda Galaxy as M31 because it is the 31st object listed in the Messier Catalog, a list of astronomical objects compiled by French astronomer Charles Messier.