Sean Coffey, UCLA

The life expectancy of Californians decreased by about three years as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a study by UCLA researchers and colleagues published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

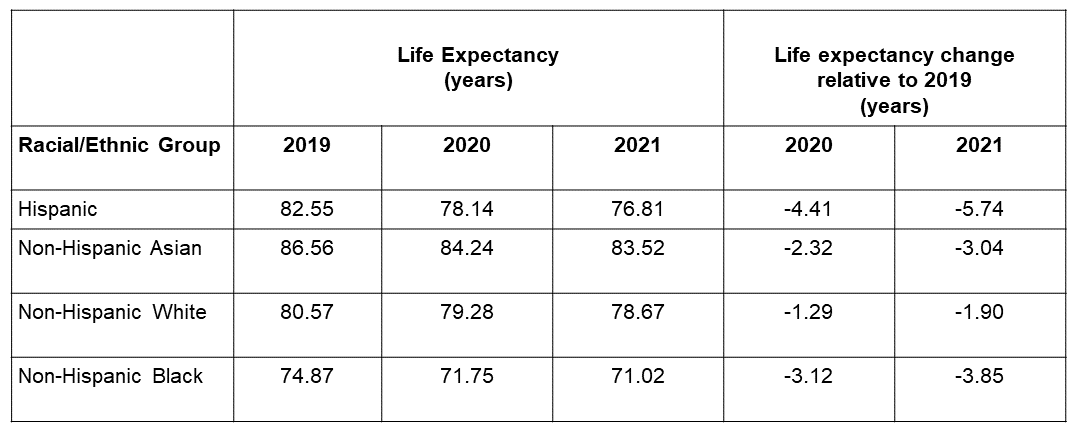

The research further shows that life expectancies for Hispanic, Asian and Black Californians decreased more than for white Californians and that the gap in life expectancies between those living in the highest- and lowest-income census tracts increased, from a difference of about 11.5 years before the pandemic to more than 15 years in 2021.

“Our findings are another troubling sign of how the pandemic’s impact was not felt evenly across all communities,” said study co-author Till von Wachter, a UCLA professor of economics and director of the California Policy Lab’s UCLA site. “Policymakers can use these findings to craft a more equitable response now, and also to inform how we plan for future public health crises.”

In their analysis of 1.9 million deaths in California between 2015 and 2021, the multi-campus research team calculated that life expectancy for Californians fell from 81.40 years in 2019 to 79.20 years in 2020, and down to 78.37 years in 2021. This study demonstrates that the reduction in life expectancy continued from 2020 into 2021, despite the availability of vaccines for much of 2021.

Life expectancy is not the average life span of individuals in a society but a hypothetical measure based solely on the mortality rates observed in a given year. It estimates how long a cohort of newborns could expect to live if it experienced the mortality rates of that specific year throughout their entire lifetimes. In the current study, life expectancy captures how much life was lost collectively within a population during the pandemic years, and it illustrates the dramatic differences in the pandemic’s impact across communities of different socioeconomic status.

Hispanic populations in California lost 5.7 years of life expectancy between 2019 and 2021, while Black populations lost 3.8 years, Asian populations lost 3.0 years and white populations lost 1.9 years, according to the study. During this time, income also became more tightly correlated with life expectancy than it had been previously.

“We’ve had indications that the pandemic affected economically disadvantaged people more strongly, but we never really had numbers on actual life expectancy loss across the income spectrum,” said lead author Hannes Schwandt, an assistant professor at Northwestern University's School of Education and Social Policy. “I am shocked by how big the differences were and the degree of inequality that they reflected.”

The study is based on an analysis of restricted death data obtained from the California Comprehensive Death Files maintained by the California Department of Health.

“In California, Hispanic individuals have historically lived longer than white individuals, but the pandemic upended that, as the life expectancy for Hispanic Californians decreased by about six years, three times as high as the decline for white Californians,” said co-author Jonathan Kowarski, a research fellow at the California Policy Lab and a doctoral student in economics at UCLA.

In addition to Schwandt, Von Wachter and Kowarski, study authors include Janet Currie of Princeton University, and Steve Woolf and Derek Chapman of Virginia Commonwealth University.