Nicole Freeling, UC Newsroom

When people think of UC students, they usually think of undergraduates. But University of California campuses also host thousands of Ph.D. students — the best and brightest from around the world — who advance learning, teaching and original research across the system.

Together, UC’s 26,000 doctoral students are a powerful source of ideas and innovation for the state, and a foundation of UC’s excellence:

- UC grad students serve as teachers and mentors to UC’s 200,000 undergrads, acting as a bridge between the learners and creators of new knowledge.

- They advance the university’s research mission, pursuing new avenues of inquiry, and serving as key partners with faculty in advancing research.

- They launch start-ups — creating roughly one every two weeks.

- And they go on to become the next generation of leaders in academia, industry, government and public service.

On Wednesday, April 19, a delegation of UC graduate students will travel to Sacramento to talk about their work, and encourage lawmakers to support UC’s efforts to enroll an additional 900 graduate students.

They will meet with lawmakers to show how their research is tackling issues critical to California, from helping stroke patients regain movement to heading off the next drought.

Here is a sampling of their research:

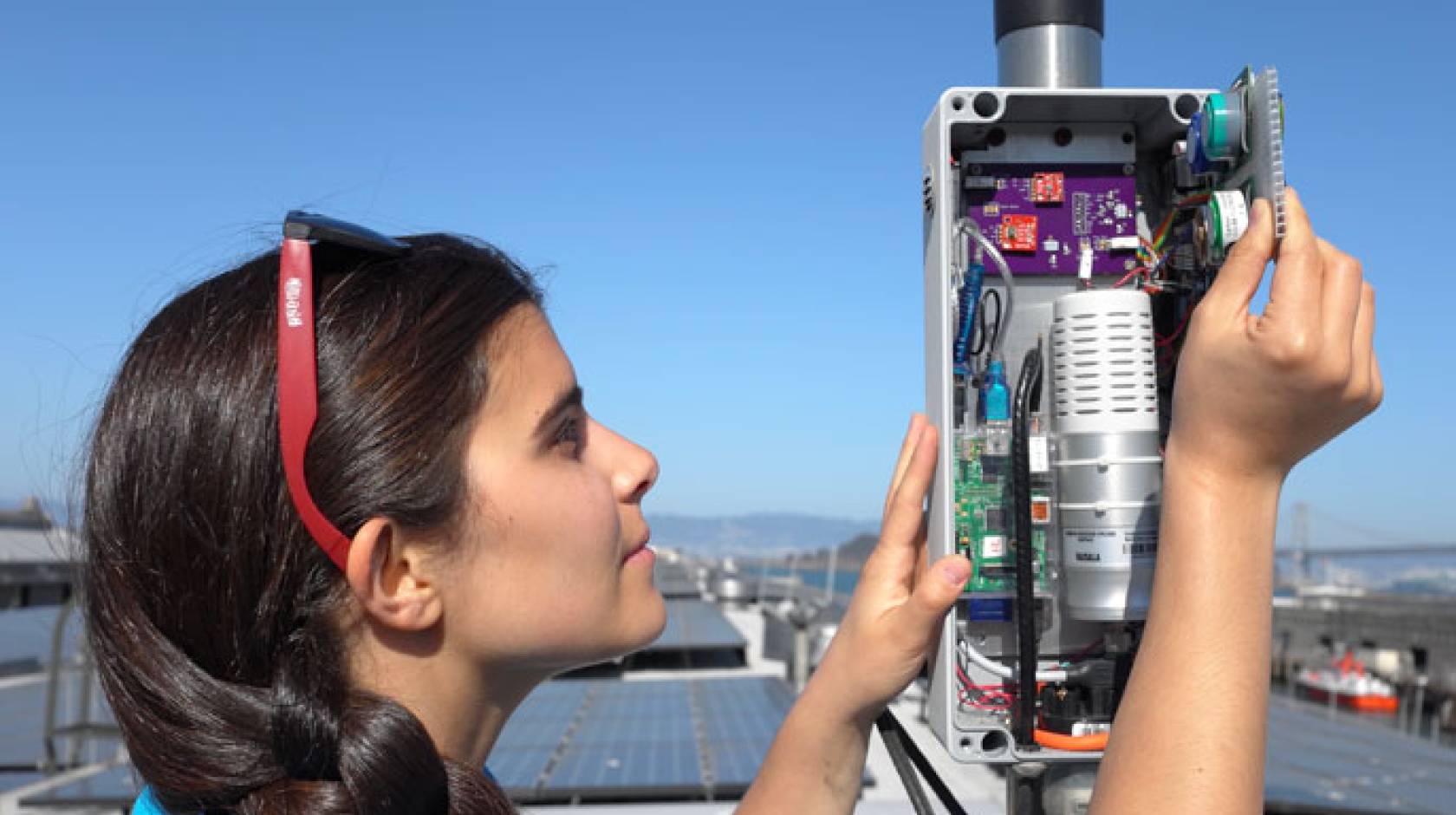

A local picture of climate pollution

What if we could look neighborhood by neighborhood to detect the presence of greenhouse gases and see how they change from day to day? UC Berkeley chemistry grad student Alexis Shusterman — with help from the National Science Foundation — has devised rooftop CO2 monitors that do just that.

The devices — which Shusterman designs and installs with a small team of other scientists — provide a highly localized view of climate pollution and how it changes daily in relation to traffic, weather and other conditions. “If you monitor closer to potential sources, you can determine where the pollution is coming from,” Shusterman said. “It can help you zero in on the factors that contribute to climate change and look at how those factors compare.”

Learn more about Shusterman's CO2 monitors.

Retraining the brain to reverse paralysis

Credit: Courtesy of Elena Zhukova

Engineers have developed technology — known as a brain-computer interface – that enables people to power prosthetic devices with their mind. Now, researchers like Sumner Norman are looking to take that one step further by using the technology to help restore function in paralyzed limbs.

The UC Irvine mechanical & aerospace engineering grad student uses brain-computer interface technology together with rehabilitation robotics as a kind of brain-based physical therapy. His research, funded by the National Science Foundation, helps those who have lost fine motion in their hands. The goal: stimulate damaged neural pathways so people with stroke can regain movement.

Learn more about Norman's research.

Finding smarter ways to prescribe pain meds

Credit: Courtesy of Michelle Keller

UCLA health policy grad student Michelle Keller has crunched medical records and other data to track how people use opioid medication prescribed after surgery. She's also looking to understand how clinicians make decisions about prescribing opioids. Her findings thus far: prescribing decisions aren't always clear-cut and doctors still rely on their gut instincts to figure out who might be at risk for addiction.

Yet, according to Keller, the data show most patients don’t use meds as given: Half don’t use the painkillers they are sent home with — while another three to seven percent are still using them months after surgery, long after postsurgical pain has worn off.

With increasingly sophisticated ways to collect and analyze patient data, Keller is looking to devise systems that can help doctors manage use of addictive medications, cutting down on unneeded prescriptions and flagging those at risk for getting hooked.

Banking rain for dry years

Credit: Courtesy of Sarah Beganskas

What if we could collect water during floods and store it underground until the next drought? With funding from the National Science Foundation, UC Santa Cruz earth sciences grad student Sarah Beganskas studies how ponds could help us do just that.

The basins collect rainfall, filter it to remove pollutants as it seeps into the ground, and funnel it into underground aquifers to recharge California’s groundwater supply. The ponds capture water that would otherwise be lost as runoff, resulting in overwhelmed creeks, hillside erosion and flooding.

With just one heavy rain, a pond at a Watsonville field site collected 80 acre-feet of water — enough to meet the needs of 160 families of four for a year. “A storm can replenish surface water really quickly, but for groundwater, it’s a different story,” said Beganskas. “Especially in years like this, we want to collect as much rain as we can and get it into the ground.”

Learn more about Beganskas's research.

Creating more powerful solar cells

Credit: Courtesy of Fatemeh Barati

UC Riverside physics grad student Fatemeh Barati studies ultrathin materials — only one atom thick — that could prove much more powerful than today’s technology in capturing and storing energy from the sun.

“When certain materials are thinned down to a few atomic layers of thickness, novel physical properties are observed in them,” said Barati. “Improved design of solar cells by these ultrathin materials increases their efficiency, and makes them great successors to the other types of energy sources.”

As a primary school student growing up in Tehran, Barati was a member of the Youth Mathematicians Community of Iran. “Then I saw a movie explaining Einstein’s theory of relativity that really captured my imagination, “ she said. “I thought, ‘This is even more interesting than math.’”

That passion has led her from her home in Iran to UC Riverside, where she is a research assistant in the Quantum Materials Optoelectronics lab. “I will never give up the joy that physics brings to me,” she said.

Preparing for drought and flood

Credit: Courtesy of Tashiana Osborne

When it comes to rain and snow, California can be boom or bust. But as the state’s epic drought gives way to one of the wettest winters on record, officials are looking to understand what might be driving these wild swings between drought and deluge.

UC San Diego oceanography grad student Tashiana Osborne is investigating the number one cause: changing patterns in the ribbons of wet air coming to California’s coast. Their strength and temperature, where and how they hit the coast and travel inland — or whether they reach land at all — affects the amount of rainfall and snowpack each region gets.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, Osborne is looking to map and track the rain and snow from these sky rivers. Her work will help officials predict and prepare as extreme weather becomes the new normal.

Targeting cells to take on diabetes

Credit: Courtesy of Dan Holohan

In the case of Type 1 diabetes, an overactive immune system destroys the body’s ability to make insulin. UC San Francisco biomedical sciences grad student Dan Holohan tests targeted, molecular therapies that could activate the cells charged with refereeing the immune system and blowing the whistle when it overreacts.

In recent years, researchers have seen some success against cancer by using the body’s own immune system to home in on and deliver therapy to diseased cells. Holohan’s research, funded by the National Institutes of Health, seeks to use the same approach by using a patient’s blood cells to deliver therapies that goose the functioning of helpful cells.

“We’ve focused a lot on killer cells. But can the same technology work to prevent disease?” he said. “If we can stimulate these cells that tell the immune system when to stop, we can potentially prevent it from responding to false threats.”

Solving the mystery of why seabirds eat plastic

Credit: Courtesy of UC Davis

UC Davis ecology Ph.D. Matthew Savoca studies why marine animals like sea turtles and albatross are drawn to eat the plastic they find in the ocean, often with tragic results. The answer: They are lured by its sulfurous odor which, to them, signals a tasty meal.

Savoca found that birds drawn to the smell of a particular chemical compound consume nearly six times as much marine plastic as other species. Using equipment made for detecting sulfur in wine, he tested to see whether sea-soaked plastic might be emitting the compound. His hunch was right: The plastic provides a home for algae, which combines with the decaying plastic to give off a smell that seabirds detect as a delicious bouquet.

The result is an olfactory trap that threatens not just seabirds, but species such as the Northern anchovy, a fish economically and ecologically critical to California.

The findings suggest plastic may be a greater threat than previously suspected. “If plastic looks and smells like food, it is more likely to be mistaken for prey than if it just looks like food,” Savoca said. “Reducing marine plastic pollution is a long-term, large-scale challenge, but figuring out why some species [are drawn to it] is the first step toward finding ways to protect them.”

Learn more about Savoca's research into seabirds and plastics.

Comparing the ‘water footprint’ of crops

Credit: Courtesy of Lorenzo Booth

Lorenzo Booth, an environmental systems grad student at UC Merced, compares the resource demands of crops using a measure called the water footprint. The measure looks at how much water it takes to produce, say, an apple versus an almond, and how that varies by location and agricultural practice.

The calculus takes reams of publically available data — precipitation data from weather stations, land use surveys, satellite measurements and USDA data — and plugs it into a formula to produce an estimate of water demand.

In addition to comparing the resource-intensity of various crops, the tool can also help growers compare different approaches and locations to optimize their resource use.

Booth is working to develop a simple, open source calculator that people can use to drive both farming and consumer choices. “If you can see how many gallons of water are in an apple or a pound of beef, and how that changes depending on where you are,” he said, “that can help you make all kinds of decisions.”

Learn more about Booth's research.

Powering greater use of electric vehicles

Credit: Courtesy of UC Santa Barbara

One way to make electric cars more convenient: Let people plug in at work. UC Santa Barbara environmental sciences grad student Victoria Greenen is working with the California governor's Office of Business and Economic Development to make that possible. She is helping officials determine the infrastructure needed to reach a goal of 1 million zero-emission vehicles on the road by 2020.

Her research project, Go-Zero, develops strategies to encourage public and private parking facilities to locate charging systems at or near workplaces. With 40 percent of California’s greenhouse gas emissions coming from cars and other transportation, Greenen said, moving toward greater use of zero-emission vehicles is critical to meeting Gov. Jerry Brown’s ambitious climate goals.

“As a graduate student and as a citizen, I am driven to find solutions to climate change and the many impacts it will have,” Greenen said. “UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School [does] a really great job of making sure that the classroom is directly connected to the real issues that need to be solved.”

Learn more about Greenen's research and her project, Go-Zero.