Laura Kurtzman, UC San Francisco

In the late 1980s, when smoking was still allowed on some airline flights, California boosted its tax on cigarettes from 10 to 35 cents a pack, devoting 5 cents to programs to prevent smoking.

The newly created California Tobacco Control Program funded anti-tobacco media campaigns and community programs to try to improve public health, but some questioned whether the efforts were worth the cost.

Now comes an answer: For every dollar California spent on smoking control, health care costs fell by $231.

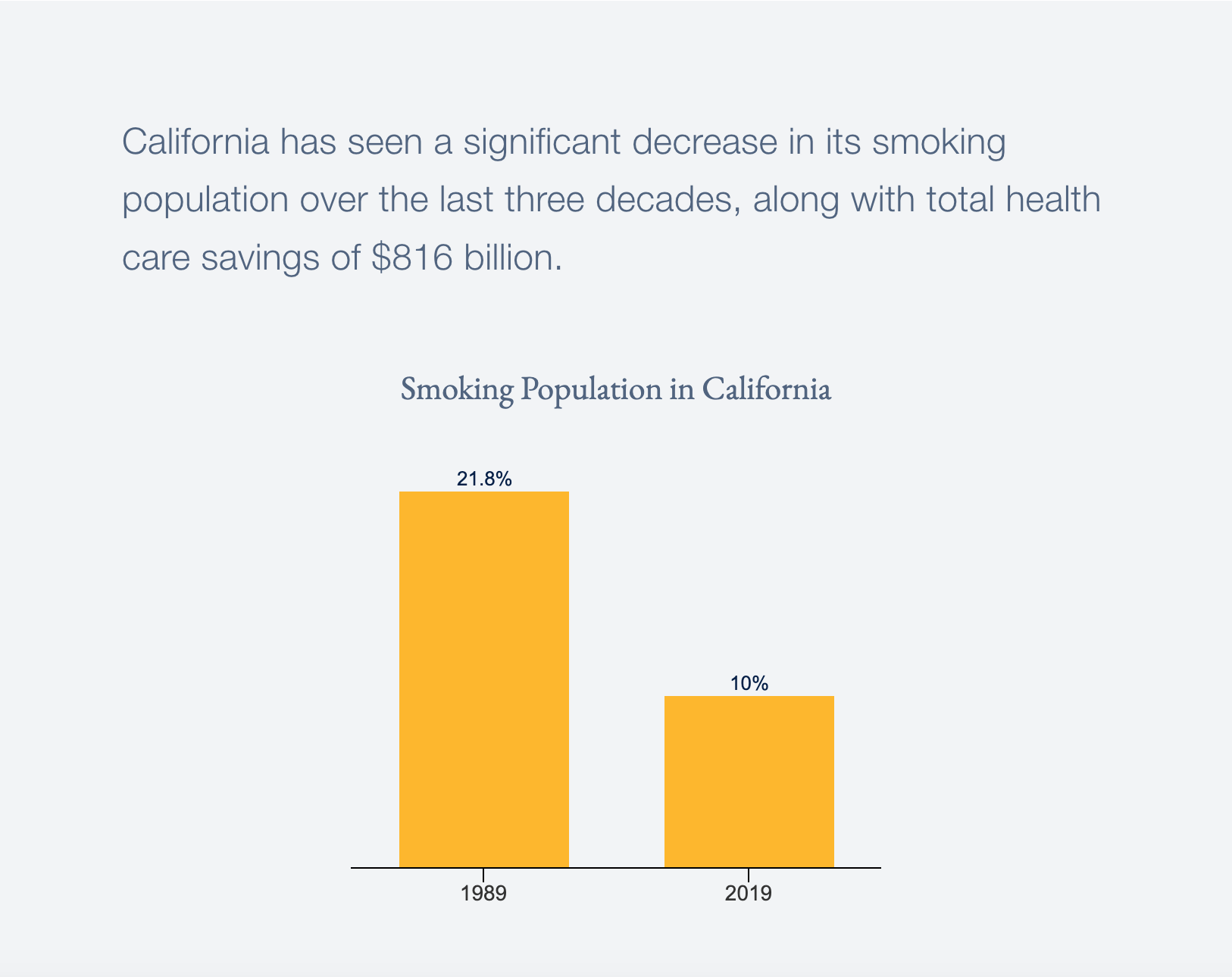

Over three decades that witnessed historic lawsuits and expanding smoking bans, California’s smoking population fell from 21.8 percent in 1989 to 10 percent in 2019. Its anti-tobacco program accounted for 2.7 of those percentage points, which may seem small but yielded large savings. Those who didn’t quit ended up cutting back by an average of 119 packs per year in response to the program, according to the study, which appears March 16 in PLoS One.

Senior author Stanton Glantz, Ph.D., the recently retired founding director of the UCSF Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, summed up the findings this way: “Tobacco control programs save a fortune.”

Over the 30-year history of the program, Californians pocketed $51.4 billion they would otherwise have spent on cigarettes. Total health care savings came to $816 billion.

“The return on investment is gigantic,” Glantz said. “These programs aren’t just saving lives and making people feel better, they’re also saving people money.”

Shaping anti-tobacco policy

Doing the econometric work to track the relationship between three types of spending — state tobacco control, consumer tobacco purchasing and health care expenses — over three decades were lead author James Lightwood, Ph.D., a UCSF associate professor of clinical pharmacy, and Steve Anderson, a financial industry forecasting expert. They developed a predictive variation of a model that Lightwood and Glantz first developed using 1989-2008 data and updated estimates of the program effect.

The model has held up over 30 years, almost 10 years beyond the original sample, through changing economic conditions and levels of California tobacco control spending, according to Lightwood.

“This paper significantly strengthens the case that there is a causal relation between tobacco control and smoking reduction,” Lightwood said.

The authors said the modeling results can help shape tobacco policy in states considering tobacco control measures and in those where support for existing programs may be wavering. The forecasting methods used in the paper are very much like those that large businesses use to inform major business decisions, Anderson said.

“Any state with a high level of smoking that launches a substantial, long-term program should get results similar to California’s,” Lightwood said. “But public policy has unique challenges. The political expediency of short-term thinking dogs many tobacco-control efforts.”

California is large and diverse, spanning rural and urban areas, and its population includes many races and ethnicities across the socioeconomic spectrum.

“California is so big that it can be considered average in many ways relevant to the evaluation of a tobacco control program,” Lightwood said.

Benefits grow over time

In previous research, Lightwood and Glantz have shown short-term cost benefits of tobacco reduction — heart attacks, strokes and low birthweight decline quickly. The current paper models both the short and long-term effects of state programs, which also reflect declines in slower-to-emerge diseases, such as lung cancer.

“The benefits grow over time as more and more diseases are prevented,” Lightwood said. “If you do a less comprehensive program for four or five years, then it’s hard to detect much change in the face of year-to-year variability and the program is vulnerable to attack. But, when the program is large, long-term and comprehensive, like California’s, we can confidently conclude that there are large and immediate benefits that grow with time.”

The new findings confirm that tobacco control efforts spur smoking reductions and that even a seemingly small reduction in smoking contributes to the state’s tobacco control program, quickly and significantly driving down health care expenses.

“Tobacco control,” Glantz said, “is one of the strongest things you can do for medical care cost containment.”