Kat Kerlin, UC Davis

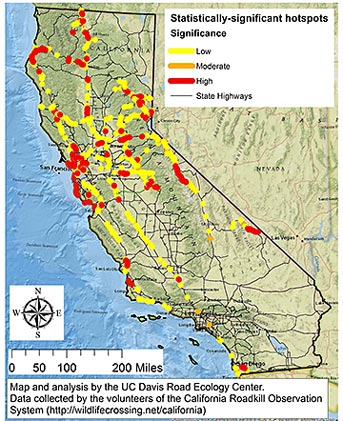

A new report of vehicle and wildlife collisions along California’s highways combines roadkill data with preliminary crash data to identify hot spots that concern both public safety and conservation.

The 2016 report from the UC Davis Road Ecology Center pinpoints stretches of highway where wildlife-vehicle conflicts are most common. It drew largely from the thousands of volunteer scientist observations submitted into the California Roadkill Observation System, which also maintains an interactive map of the last 90 days of roadkill incidents and species throughout the state.

Credit: UC Davis Road Ecology Center

Data from the California Highway Patrol and Caltrans indicated there were about 700,000 crashes and other incidents on California’s roads and highways between February 2015 and February 2016. Of those, about 6,000 involved conflict with wildlife. These could involve animals running across the road, collisions with wildlife, or accidents resulting from people swerving to avoid hitting wildlife. Preliminary analysis of these crash data point to certain highways being hot spots for wildlife-vehicle conflict. A more detailed analysis of the crash data is expected this summer.

“Because the carcass hot spots and crash hot spots are identifiable and somewhat predictable, we can go to certain places on the landscape and protect wildlife and drivers from collision,” said Fraser Shilling, co-director of the UC Davis Road Ecology Center and director of the California Roadkill Observation System. “We have the necessary information to help prevent these collisions from occurring.”

California mountain lions are one example of a species threatened by highway traffic.

“For California’s mountain lions, the loss of safe passages not only results in dangerous vehicle-wildlife collisions, it reduces the numbers of individuals in a population, said Wendy Keefover, carnivore protection manager for the Humane Society of the United States. “Worse, without safe crossing points, some subpopulations of mountain lions face inbreeding problems, and those subpopulations could disappear forever.”

Major hot spots in the report

San Francisco and the Bay Area

The Bay Area has the most hot spots for wildlife carcasses and crashes in California. Interstate 280 is the report’s No. 1 crash spot and also a hot spot for roadkill.

“We now have the data showing that Interstate 280 is a death trap for wildlife and that wildlife overpasses and underpasses save lives — both human and nonhuman,” said Camilla Fox, founder and executive director of Project Coyote. “It is time that Caltrans and state legislators do what’s necessary to reduce road mortality and the dangers to both people and wildlife on Interstate 280.”

Persistent hot spots for roadkill include U.S. Highway 101 in Marin County south to Petaluma. Observations of native western gray squirrel carcasses along state Route 12 through Sonoma Valley are frequent as well. However, Shilling notes that squirrels will use rope bridges to cross roads if they receive them. “So that’s a good spot to be able to fix a problem,” he said.

An East Bay hot spot is where Interstate 580 runs to the west of Interstate 680. That stretch represents a common theme played out along U.S. 101, I-680, state Route 13, state Route 1 and I-280, as well: Animals often attempt to cross the road when open space is bisected by highways.

Sacramento

The Interstate 80 causeway over the Yolo Bypass continues to be a major spot for bird collisions. U.S. Highway 50 beginning in the El Dorado Hills to Pollock Pines, and I-80 near Auburn are also areas where vehicles often hit animals, including mule deer, which can pose a significant risk to drivers.

Southern California

While there are fewer observations from Southern California in the California Roadkill Observation System, the report identifies state Route 94 in San Diego County as a hot spot. Other spots include state Route 126 in Ventura and U.S. 101 near Lompoc and San Luis Obispo.

Sierra Nevada

State Route 89 north of Lake Tahoe continues to be an active roadkill area, as is state Route 49 along the foothills.

Shilling notes that wildlife living in and near national parks and other protected areas can also be threatened by vehicles. For example, many reptiles, such as snakes, lizards, small mammals and endangered desert tortoises get hit in Death Valley along state Route 190. Likewise, wildlife carcasses are often found on both state Route 120 and state Route 140 near Yosemite National Park.

“So our protected spaces aren’t so protected, whether it’s an open space in the Bay Area or in the national parks,” Shilling said. “Traffic is leading to the loss of wildlife of a lot of different stripes.”

Funding and citizen participation

Individuals interested in submitting roadkill observation information may visit the California Roadkill Observation System website.

The new report, produced by the UC Davis Road Ecology Center, was not supported by any external funding.