Nina Bai, UCSF

Ancient practices like tai chi and yoga have long focused on breathing as a way to control the body’s energies, and in recent years, they’ve been touted as antidotes to the stress of modern life. But can simply inhaling and exhaling a certain way fight stress and boost your health? Are there evidence-based interventions to reduce stress?

Researchers at UCSF are launching a study to examine the impact of short-term positive-stress interventions, including breathing techniques, on mood and physiological health. They say it is the first to look at how brief periods of controlled stress could protect the body from long-term stress.

Chronic stress — perhaps from a high-pressure job or caring for a sick relative — has been linked with depression and earlier signs of aging, such as high inflammation and shorter telomere length, as well as earlier onset of diseases like cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The hope is that practices that promote so-called stress resilience may prevent or reverse these harmful changes, said Elissa Epel, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry, who is one of the leaders of the study.

The stress paradox

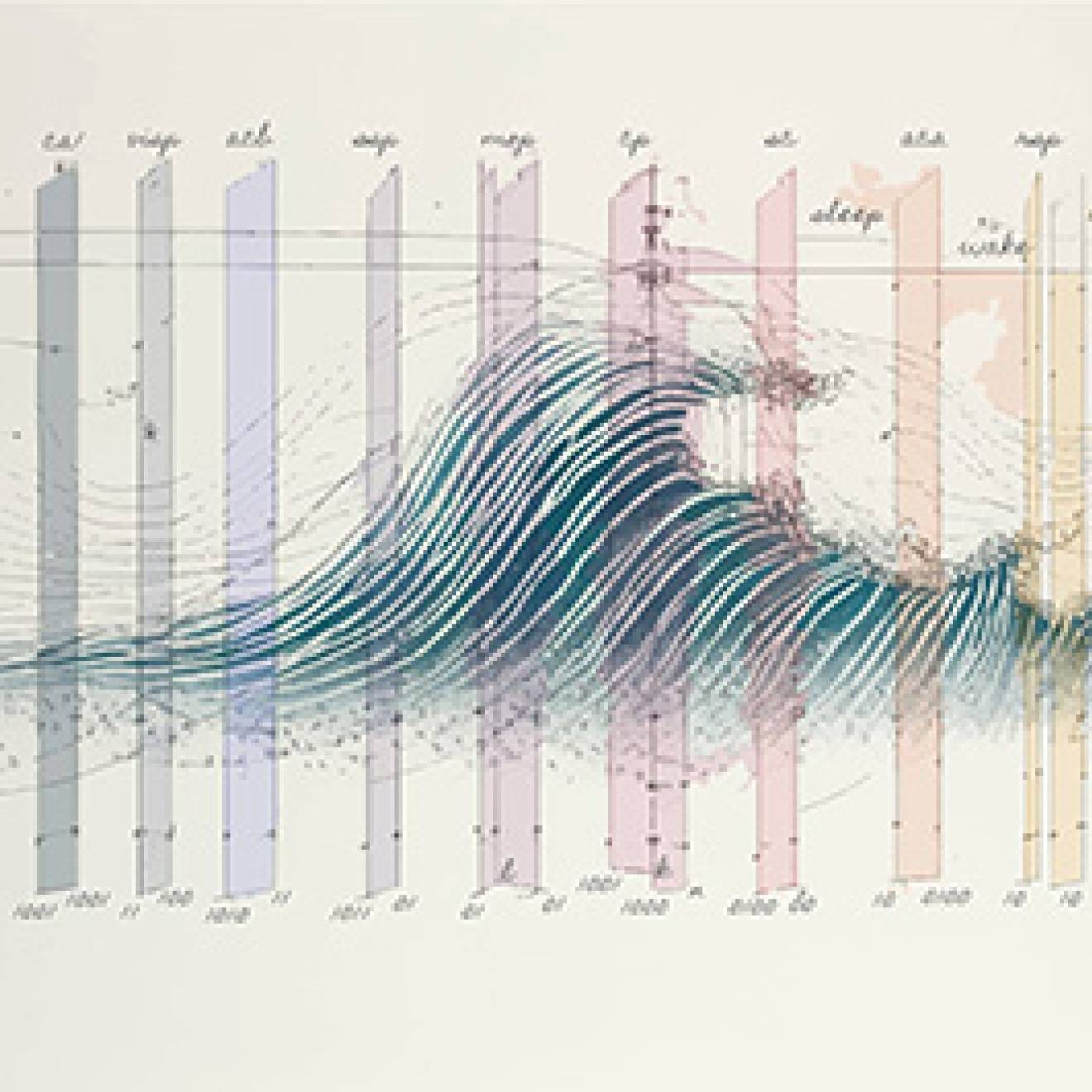

Credit: Susan Merrell

Epel thinks certain practices may activate a seemingly paradoxical process, known as hormesis, in which exposure to short-term stress actually makes cells more resilient. Unlike long-term stress from work or relationships, which wears out cells, brief periods of stress could do just the opposite.

“What we know from studies in cells and worms and mice is that short-term stress is life-lengthening,” said Epel.

In humans, short intense workouts or hyperventilation and breath-holding — when done safely — could create a healthy stress response in the body. But until now no one has rigorously tested this in humans.

“We are testing whether, when we apply stress in a manageable way, that’s improving cell-aging — such as turning on activities in the cell that clean out junk and debris and creating a younger cell,” said Epel.

Epel believes the effect should extend beyond cells to mood as well. “Short-term stress training may elevate positive mood and make us less vulnerable to feeling anxious or depressed when stressful things happen in our life,” she said. The new study is supported by a $1.1 million gift from the John W. Brick Mental Health Foundation, which supports evidence-based research on how holistic treatments — such as exercise, nutrition, healthy lifestyle choices, and mind-body practices — benefit mental health.

Stress resilience takes practice

The researchers are recruiting healthy women experiencing high levels of psychological stress to test out different daily habits and will assess their effect on stress, mood, and physical health. Every morning for several weeks, one group will meditate, another will do a brief, intense aerobic workout, and other groups will practice breathing techniques. One breathing technique, for example, involves a series of quick deep breaths followed by periods of breath-holding. These breathing techniques are becoming popular, but are relatively untested.

Credit: iStock/FatCamera

The researchers will examine how these three daily practices affect the women’s response to future stressors — how well their bodies regulate and maintain balance in the autonomic nervous system, the immune system, and metabolism, for example.

“This is a unique opportunity to test whether short-term stressors on the body can accumulate to long-term effects in psychological and physical resilience,” said Wendy Berry Mendes, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and a co-leader of the study. “This logic is, in principle, similar to why exercise has benefits for our physical health, however, in this study we are looking at non-metabolically demanding tasks and examining if the same benefits might accrue.”

Evidence-based treatments

The researchers plan also to examine how the practices might relieve depressive symptoms and optimize interventions to help people with major depression. “The most commonly used treatments for depression are pharmaceuticals,” said Epel. “But now it’s clear that they don’t work for the vast majority of people with depression, and their side effects can be serious. This underscores the need for both prevention and biobehavioral treatments.”

Breathing strategies could be an accessible way for anyone to build their stress resilience. But until the study results come in, Epel said it’s still a “big leap” to claim human health benefits of short-term stress based on worms, animals, and anecdotes. “That’s why we’re being extremely rigorous,” she said. “We are grateful to the Brick Foundation for supporting innovative studies that could lead to new knowledge and treatments.”

“We are very excited to sponsor this UCSF study,” said Victor Brick, co-founder of the Brick Foundation. “We want to change the way people treat mental health and we think that evidence-based research is the best way to do that.”