David Danelski, UC Riverside

If a thirsty Southern California and southeast Australia share a common need, it is to capture and store more water from the fewer but heavier rainstorms that are becoming normal with climate change.

UC Riverside public policy professor Kurt Schwabe was just awarded a Fulbright Distinguished Chair Fellowship to collaborate with Australian scientists to better capture and store water as the planet warms. He will work with policy experts to ready Australia and California to recharge managed aquifers, establish groundwater banks, and create water markets to reduce the impacts of drought associated with climate change.

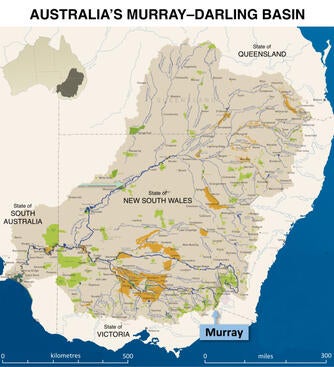

More specifically, the researchers will develop an institutional structure for the use of depleted aquifers for water storage in California and in Australia’s expansive Murray–Darling basin region, which has tributaries of the Murray River, Australia's longest river.

The U.S. Department of State provides Fulbright Fellowships to scholars with distinguished research and teaching records whose work play a critical role in diplomacy by fostering stronger relations between the United States and ally nations through the sharing of knowledge, expertise, and innovation. The Distinguished Chair Fellowships are among the most prestigious awards in the Fulbright program and are awarded to scholars who develop a project of critical importance to the U.S. and partner countries. They come with modest stipends to help cover the scholars’ travel, living, and research expenses.

Schwabe’s fellowship will return him the Murray-Darling basin, where he has done work as environmental economist periodically for 16 years. Schwabe and his family will be staying in coastal city of Adelaide during the fellowship period, which covers the first six months of next year.

Kurt Schwabe

He will work with an array of academic, government, and non-governmental organization officials to develop strategies to capture, store, and distribute greater proportions of stormwater runoff for use by farms and municipalities.

“We need to capture and store more water to help us get through increasingly longer periods of aridity and drought that, unfortunately, correspond with longer periods of more extreme heat,” he said. “Our current storage 20th century water infrastructure isn’t built to capture and store 21st century rainfall events that are going to be fewer and more intense. So, we have less of an opportunity than in the past to capture those surplus flows, and to store them.”

Schwabe will focus his expertise on using the excess capacity within naturally occurring aquifers to store water for future irrigation and municipal use, while recognizing the connections between surface and subsurface water systems, such as groundwater fed springs or streams that help sustain flows needed for wildlife. Guided by institutional structures, these strategies will involve diverting storm runoff water to level fields and catch basins where it can percolate to the aquifers for later retrieval via pumping.

Groundwater storage in aquifers comes with far less financial and environmental costs than damming rivers and building reservoirs, he said. What’s more, excessive and unregulated pumping of water from wells over the past 40 years has created myriad problems, including land subsidence, which will worsen unless actions are taken.

Depleted aquifers and managed aquifer recharge, however, now offer society a low-cost way to store water, while groundwater banks and water markets are a means to fairly allocate water to periods and places that will reduce the impacts of climate change.

As an economist and policy expert in water and drought for over two decades, Schwabe recognizes the complexity of the problem and the need to consider multiple criteria and involve a broad coalition of partners.

The Murray-Darling basin in Australia.

“It's a complicated problem,” Schwabe said. “But at the end of the day, you want systems that strive to achieve efficiency so that you utilize the least amount of resources for the greatest benefit to society; are equitable, so that the returns to your system accrue fairly across stakeholders, which includes the public; and are sustainable.”

Schwabe’s work is expected to benefit both a parched Australia and California, particularly areas within the Central Valley whose aquifers have been significantly depleted. The project will build upon the experiences California has with groundwater banks and recent experiments with managed aquifer recharge, and couple with the experience Australia has with developing the most mature water markets globally.

Australia is a world leader in terms of trading permanent and temporary surface water rights.

“Working with the researchers over there, I can look at how they've set up their surface water markets, and they can look at how we set up our groundwater banks,” Schwabe said. “If we combine the two, then we get the best of both worlds.”

Kurt Schwabe and his daughter Petra at a vineyard in Australia in 2015.