Stuart Wolpert, UCLA

Exposure to influenza viruses during childhood gives people partial protection for the rest of their lives against distantly related influenza viruses, according to a new study in the journal Science.

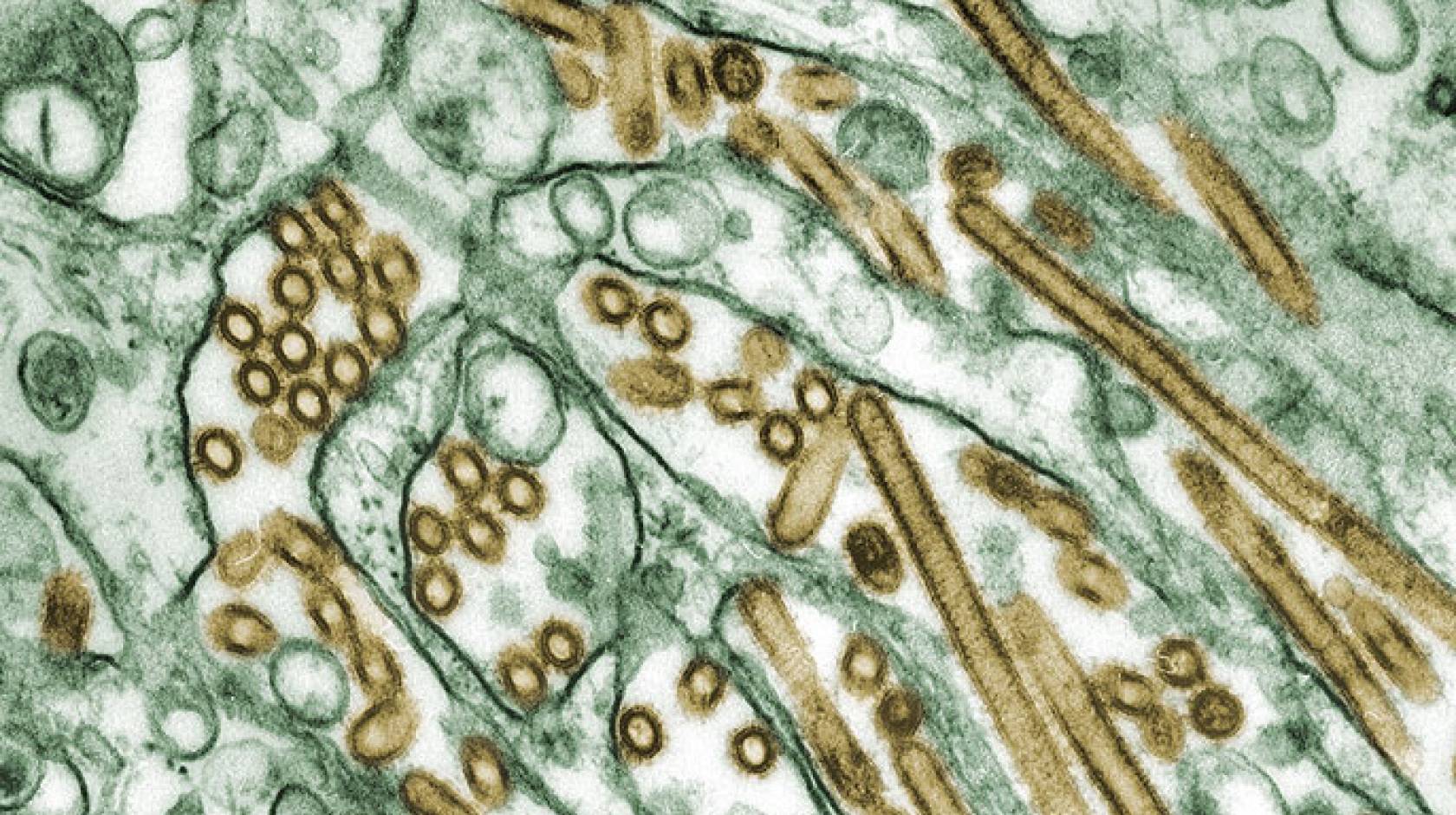

Credit: Courtesy of Katelyn Gostic

Scientists from UCLA and the University of Arizona analyzed data from all known human cases of two types of avian influenza — more than 1,400 people in all — and found evidence of previously unrecognized human immunity against several viruses that circulate in animals but have not previously circulated in humans. They also discovered that people born before 1968 are more susceptible to certain viruses, while people born during or after that year are more at risk for different strains of the flu.

The viruses charted by the researchers were H5N1 and H7N9, which have each affected more than 700 people, mostly in Asia and the Middle East, making them the flu strains that pose the greatest concern for emergence from animals to humans. H5N1 and H7N9 also both have shown the ability — albeit a very limited one — to be transmitted from human to human, which raises the possibility that a slight adaptation in either could trigger a pandemic.

Since 2013, when H7N9 was first detected, scientists have been puzzled by the fact that the two viruses tend to affect distinct age groups: Children and young adults are more likely to be infected with H5N1, while H7N9 disproportionately affects older adults.

Several explanations for this phenomenon have been proposed, but the UCLA and Arizona researchers suspected that the cause was people’s pre-existing immunity, said Katelyn Gostic, a UCLA doctoral student who is the study’s lead author.

Flu varies by birth year

The researchers can now predict with reasonable precision whether a person will have immunity against new influenza strains based on their birth year, which indicates the seasonal flu virus that was most likely to have caused their first flu infection during childhood.

“Our findings show clearly that this ‘childhood imprinting’ gives strong protection against severe infection or death from two major strains of avian influenza,” said James Lloyd-Smith, a UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and the study’s senior author. “These results will help us quantify the risk of particular emerging influenza viruses sparking a major outbreak.”

It is unclear whether that imprinting provides strong enough immunity to prevent infection altogether, but it substantially reduces the risk for severe disease, the study reports. People born in “protected” birth years were much less likely to get sick enough to visit the doctor, be hospitalized or die from H5N1 or H7N9 infections.

The dividing line for the two age brackets, 1968, was the year of the so-called Hong Kong flu pandemic, which swept away viruses from a different genetic group that had dominated seasonal influenza for a half-century beforehand. People born during and since 1968 are more likely to have protection against H7N9, which is more closely related to the 1968 virus than to flu viruses that circulated before. People born before 1968 are likely to have protection against H5N1.

The study reports that the same methods could be used for any country with sufficient data to estimate which age groups would have the highest risk for severe disease in a pandemic.

Predicting outbreak

“These findings challenge the current paradigm, where the entire population would be immunologically defenseless in a pandemic caused by a novel influenza virus,” Gostic said. “Our results suggest it should be possible to forecast age distributions of severe infection in future pandemics, and to predict the potential for novel influenza viruses from different genetic groups to cause major outbreaks in the human population.”

Gostic added that the projections could be made based on demographic information and influenza surveillance data that’s already routinely collected by governments and public health agencies, in an effort organized by the World Health Organization.

Credit: Reed Hutchinson/UCLA

“This approach opens new frontiers in the nascent field of quantitative risk assessment for emerging pathogens,” Lloyd-Smith said. “All of the focus has been on studying properties of the viruses and ecological circumstances that drive spillover. Those factors are definitely crucial, but it turns out we can learn a lot about flu pandemic risk from information about humans, which we’ve already got.”

Michael Worobey, a University of Arizona professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, is the study’s co-senior author; and Monique Ambrose, a UCLA doctoral student, is a co-author.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant EF-0928690 and fellowship DGE-1144087), the National Institutes of Health (grant T32GM008185), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Department of Homeland Security’s Research and Policy for Infectious Disease Dynamics program of the Science and Technology Directorate.