When I was a kid, we used to visit my grandparents in their apartment in downtown Long Beach. On one visit, I noticed my grandmother speaking Spanish to another tenant. My family is Mexican American, deeply rooted in the Southwest. Her neighbor, a woman about my grandmother's age, looked to be African American, and I'd never heard someone like her speak Spanish before. I asked my grandmother about it and she responded: “Antonio, we come in all colors.”

I realized then that there was a more expansive “we” to describe people like me and my grandmother than I had assumed before: some of us call ourselves Hispanic, others Latino or Latinx, and some a combination of both or neither.

Throughout my life, I have thought a lot about what it means to be “us” and whether there is one right term. Scholar Cristina Mora, a UC Berkeley associate professor of sociology and Chicano/Latino Studies, has devoted much of her career to thinking about what it means to be Hispanic, Latino or Latinx — and how the meaning of the terms themselves has shifted over time.

How one identifies is a lifelong journey that lends itself to nuance, and not necessarily a fixed construct. Professor Mora’s research lends credence to that view. The terms themselves have evolved over time, Mora says, as has what it means to be Latinx in the United States.

Finding the right word to be counted in the Census: Hispanic

People often want to know which term — Hispanic, Latino or Latinx — is the most respectful. But it really depends on the person and context. I’ll sometimes say I’m Latino or Hispanic. Or I’ll be more specific and say Mexican American.

Mora in the video above uses a similar range of terms.

Of all of these, I use the term Hispanic the least. Yet this word might be the most important in terms of the visibility it has given to the Latinx community in the United States over the last few decades.

“Hispanic” refers to any of the peoples in the Americas and Spain who speak Spanish or are descended from Spanish-speaking communities. It was coined in the 1970s by the U.S. Census Bureau to offer a pan-ethnic name for peoples such as Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans and others, whose social, economic and political needs were often ignored.

According to Mora, before the term “Hispanic” was adopted, the census enumerators would often check off people such as Mexican Americans as “White” on the census forms.

The author's parents (Gil and Lori Campos) visit the White House, circa 1980

Similarly, I had always thought it was curious that my grandparents were categorized as “white” on both my mother’s California birth certificate as well as my father’s Texas birth certificate. It struck me because my grandfather, who is from Austin, Texas, talked about the kind of segregation he faced growing up there and how the school system would punish children simply for speaking Spanish on school grounds.

By classifying folks like my grandfather as white, it erased his community. As Mora says, “Latinos lived their everyday reality as Latinos, a sometimes Spanish-speaking world with places where they were not allowed, in swimming pools, school districts and other public places.”

In order to name the ways in which people like my grandfather were excluded from certain American institutions, “Hispanic” was adopted by the U.S. Census Bureau to both define a community but still recognize their American identity. Latino and Latin American were also proposed early on, but as Mora puts it, “Hispanic was seen as a term that could be viewed as much more American.”

By aggregating everyone under the term “Hispanic,” particularly with an eye on the upcoming 1980 census, political leaders were able to illustrate how large and important this community was on a national level.

Finding the right word for my family: Mexican American/Chicano

On the most recent U.S. census, I checked off Mexican American/Chicano for my chosen ethnic identity. For me, this most accurately fits with how I think of myself in relationship to other Americans.

Mora notes that “[Latinx] communities have identified themselves with much more localized identities. So, for example, national identities such as Mexican or Cuban have always been important and continue to be important even though these pan-ethnic and pan-racial categories exist.”

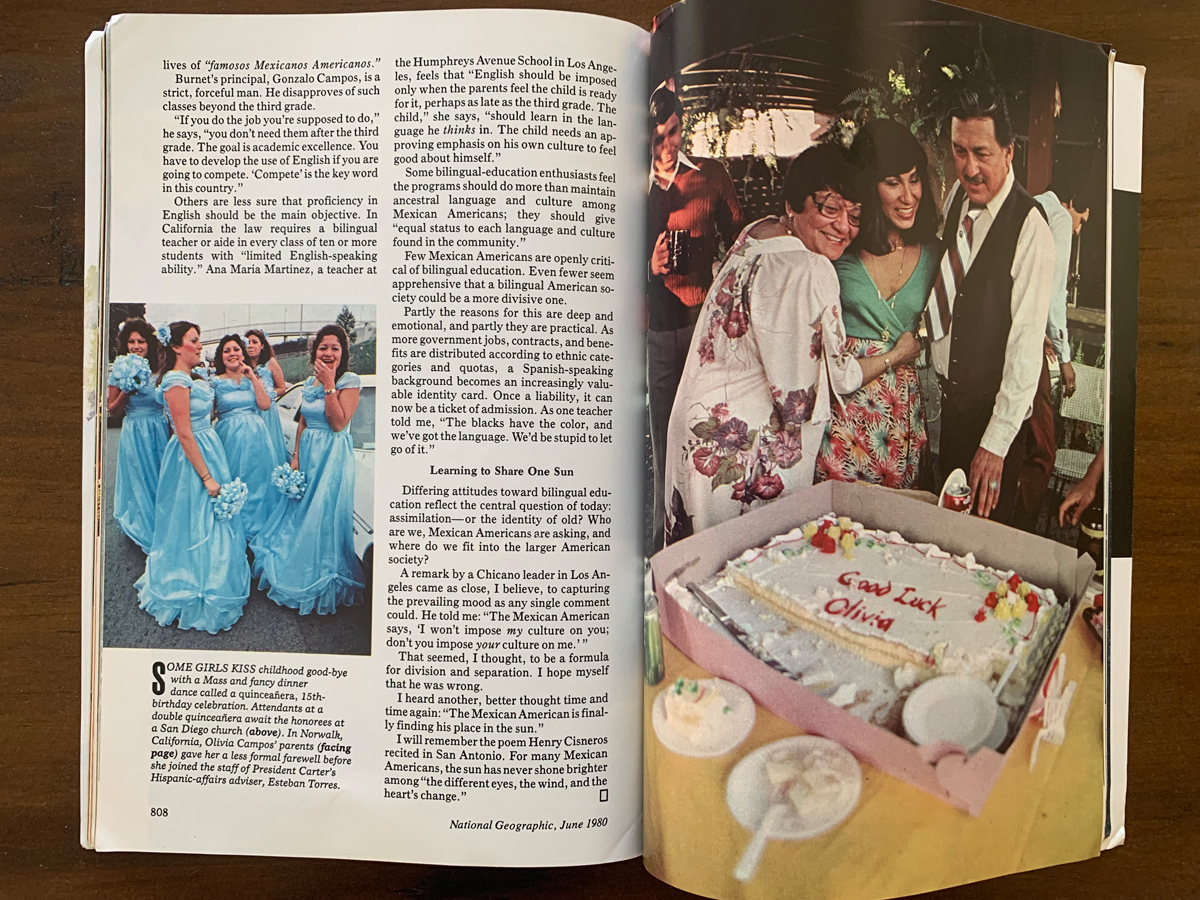

The reason Mexican American and Chicano feels most right for me goes back to my family. On my mother’s side, there are relatives whose ancestry goes back to the time before Texas was annexed by the United States. All my grandparents were born in either Texas, California or Arizona, all of which were at one time a part of Mexico. (Interestingly, a photo of my aunt and grandparents appears in the 1980 National Geographic in an article titled “Mexican Americans: A People on the Move.”)

National Geographic, Vol. 157, No. 6, from June 1980, featuring the author's aunt and grandparents. The magazine caption reads: “SOME GIRLS KISS childhood good-bye with a Mass and fancy dinner dance called a quinceañera, 15th-birthday celebration. Attendants at a double quinceañera await the honorees at a San Diego church (above). In Norwalk, California, Olivia Campos’ parents (facing page) gave her a less formal farewell before she joined the staff of President Carter’s Hispanic-affairs adviser, Esteban Torres.”

Finding the right word in the community: Latino

Between Hispanic and Latino, I will tend to describe myself as a Latino most, particularly when wanting to express solidarity with other Latinx groups in the United States.

In contrast to Hispanic, the term Latino describes any person with ancestry in Latin America, a politically defined region usually unified by the predominance of Romance languages. This definition usually includes Portuguese-speaking Brazil and French-speaking Haiti, but excludes Spain.

“In the 1990s and 2000s, ‘Latino’ was much more in vogue and had a sense that we are all connected to each other by our history of being colonized, our history of struggle versus our connection to Spain, which is what ‘Hispanic’ tends to conjure up,” says Mora.

Similarly, I tend to feel an affinity to Latino over Hispanic because it focuses on the peoples of what we call Latin America over the kind of imposed colonial cultures and institutions of Spain.

Still, it is imperfect, as it continues to mask the diversity within the Latino community, particularly Indigenous peoples, Afro Latinos, and many others. “If we only used these broad categories,” Mora said, “we’d be doing a great disservice to Indigenous Latinos and Afro Latinos and the way that national categories shape our lives.”

The terms Latino and Latin America have grown and evolved, sometimes with contradictory objectives. And as with the neologism “Latinx,” these words are continually changing.

Finding the right word to be inclusive: Latinx

I have come to embrace the term Latinx. I understand why many in the community feel it’s not quite right.

For some, the pronunciation of the word is cryptic: la-TEENGKS? LA-tin-EX? For others, it represents a kind of language imperialism by imposing a new English word onto a Spanish word and rendering it unpronounceable.

Latinx is essentially a non-binary form of Latino or Latina. The suffix “-x” replaces the “-o” or “-a” corresponding to masculine or feminine, allowing the word to resist the gender binary. (In Spanish-speaking countries, the term Latine with the suffix “-e” is circulating as an alternative to the -o/a binary.)

Mora believes that this word has increased in use in the 21st century owing to the internet and social media: “There’s certainly a big correlation between the fact that it’s Gen Z and Millennials using Latinx and that it took off on social media.”

I personally choose this word to show solidarity with queer and non-binary identity politics. The circulation of the term among college students and in academic circles makes it preferred by university outlets.

But whatever term you prefer — Latinx, Latina, Hispanic or Latino — the debate itself shows the ongoing fight for recognition and being counted is not yet over. In choosing what term to use, everyone has to ask themselves: Who is included and who is excluded? And what do we hope to accomplish when we bring forth a word and speak its power?

Antonio Campos is a writer, editor and project manager at the University of California Office of the President, and a 2008 graduate of UC Santa Cruz. He researched contemporary Latin American art for his museum studies degree from San Francisco State University.

Antonio Campos (the author)