Jim Washburn, UC Irvine Magazine

Floods in California rarely attract the sort of attention that earthquakes, wildfires or even shark attacks do. Perhaps it has something to do with the severity of an unprecedented, yearslong drought that is far from over. This winter’s deluge — particularly in the northern and central regions — was a jolting reminder that rainfall remains a deadly, destructive force to be reckoned with, though it has been many decades since the Golden State experienced truly catastrophic flooding.

Climate scientists, however, note that higher temperatures due to global warming mean the air can hold more moisture, resulting in more of the atmospheric rivers that have brought heavy rain to the state. It’s only a matter of time, they warn, before a sufficiently massive storm arrives to add to California’s legacy of devastating floods.

Inundation from back-to-back Pacific storms in 1938 resulted in 115 deaths and the destruction of some 5,600 homes in the Los Angeles area – leaving so much standing water that mail had to be delivered by the U.S. Coast Guard. When the water receded, the mouth of the Los Angeles River had shifted 22 miles from Venice to Wilmington. That was considered a 50-year flood, meaning that the level of sustained rainfall (1938’s event dropped 10 inches in the lowlands and 32 inches in the mountains) has a 1-in-50 chance of occurring in any given year.

The disaster spurred a herculean effort to mitigate the effects of future floods. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers replaced the Southland’s meandering rivers with concrete canyons fed by a network of storm drains and paved channels. That flood control system has largely served its purpose since then, but its aging infrastructure has raised doubts that it could handle a statistically overdue 100-year flood such as the one that inundated the state in 1862.

Despite these concerns, a flood control overhaul remained on a perpetual back burner. It was brought to the forefront in recent months, however, garnering headlines from the Los Angeles Times to The New York Times and rekindling interest in the subject from local governments to the California statehouse.

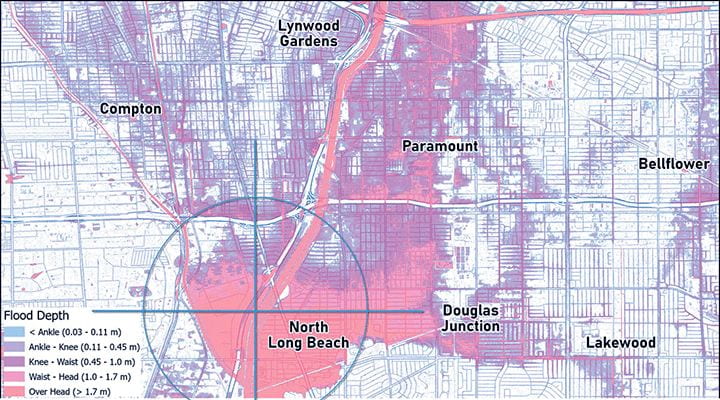

The event precipitating this was not the weekslong rain of late December and January but rather the alarming prospect of flooding raised two months earlier in a prescient, UC Irvine-born research paper published Oct. 31 in the journal Nature Sustainability titled “Large and Inequitable Flood Risks in Los Angeles, California.” Using a new flood modeling and mapping method named PRIMo (Parallel Raster Inundation Model) to show in nearly house-by-house detail the impact of a 100-year flood, the study found existing assessments to be wildly inaccurate and the aging waterway control system to be woefully inadequate for coping with a massive deluge.

“We knew the paper would get some attention because we’re saying that the number of people at risk is 30 times greater than the federally defined flood plains would suggest,” says lead author Brett Sanders, UC Irvine professor of civil and environmental engineering. “On top of that, we identified glaring racial and economic inequalities in the flooding risks that residents face.

“I am surprised, though, by the speed of the response to it,” he adds.

Scarcely a month after the paper was published, Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn cited the research findings as cause for a motion — immediately and unanimously approved — directing the county to assess its stormwater infrastructure and address inequities in the current system.

California Assemblywoman Cottie Petrie-Norris, whose 74th District includes beach cities Huntington, Newport and Laguna, as well as Irvine, says, “The paper shows just how urgent and immediate this threat can be. For a long time, when we talked about flood risks and sea level rise, people acted like it was 100 years away. The reality is that it’s here, it’s now, it’s urgent, and the state of California’s response needs to reflect that urgency.”

She adds: “UC Irvine’s research has absolutely highlighted the fact that not only are our communities at severe risk, but it’s our most historically disadvantaged communities that are at the greatest risk. We’re making investments that ensure we are moving forward equitably.”

To quantify those risks, the paper predicts that a 100-year flood could place as many as 874,000 people and over $100 billion of property in the path of floodwaters at least a foot high — “risk levels far above federally defined flood plains and similar to the most damaging hurricanes in U.S. history,” it states. (The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s estimates are notably lower, Sanders says, because FEMA accounts for river and oceanic flooding, but not rainfall, and is not current with changes in climate and land use that increase the magnitude of flood events.) The research also found that Black residents are 79 percent more likely than white residents to experience flooding deeper than 3 feet, while Latino and Asian residents are 17 percent and 11 percent more likely, respectively. The cities most at risk include Long Beach, Carson and Bell Gardens.

“Recent nationwide modeling studies have concluded that the people most exposed to flood risk are white and living in rural areas of the southeastern U.S.,” Sanders says. “However, nationwide flood hazard models tend to be least accurate in urban areas, which are home to many communities of color. When we use a more accurate modeling approach in Los Angeles, we find that the number of exposed people is far greater than suggested by national-scale models.

“Moreover, we find that the exposed populations are disproportionately Black and Hispanic,” he says. “Our work thus calls for more detailed modeling of urban flood risks nationwide to fully assess the scale and inequities of flood exposure in the United States.”

Deep waters

The Parallel Raster Inundation Model, or PRIMo, developed by UC Irvine professor Brett Sanders and run on a supercomputer enabled the first detailed mapping of compound flood risks across Los Angeles County and parts of Orange County. The model combines historical data on past floods with detailed data on topography, land use and stormwater infrastructure to estimate the depth of flooding across the region in the event of a so-called 100-year event. Deep flooding is expected within a corridor along the Los Angeles and San Gabriel rivers between South Gate and Long Beach, as shown above.

A new tool to understand flood impacts

How did the “Large and Inequitable Flood Risks in Los Angeles, California” research come to be? It’s the result of an interdepartmental effort and the innovative PRIMo computer modeling flood simulation program.

Sanders’ co-authors include fellow Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering faculty Amir AghaKouchak,

along with research specialist Jochen Schubert and grad student Daniel Kahl; Steven J. Davis of the Department of Earth System Science; Richard A. Matthew and Nicola Ulibarri of the Department of Urban Planning and Public Policy; and researchers from UC Riverside, UC San Diego and the University of Miami.

The flood risk findings had their origin several years ago when six of the paper’s authors worked together on the Flood Resilient Infrastructure and Sustainable Environments project (FloodRISE, funded by the National Science Foundation) to test the role that fine-resolution flooding simulations could play in shaping community awareness about sea level rise and in evaluating options to address it.

The first effort was in Newport Beach, where for one part of the project, Sanders and the others prepared simulations to help residents of Balboa Island visualize what they would experience during sea-rise flooding, first without an improved sea wall and then with. The City Council subsequently voted to raise much of the existing sea wall by 9 inches — work that was completed in 2018.

Some of the most important data used in the flood simulation models comes from publicly available property elevation records kept by county and city governments, which typically hire airplanes with aerial laser scanning to map the elevation of every parcel of land.

“It’s an immense amount of data to incorporate the elevation of every part of L.A. and Orange counties at a 3-meter resolution – we had something like 750 million distinct elevation points,” Sanders says. “We’re increasingly able to drill down to a household level to understand flood risks and also zoom out to a regional level. It has never before been possible to simultaneously contemplate regional-scale challenges and then bring them down to show the local consequences.”

He adds, “PRIMo allows us to do these types of simulations interactively with community stakeholders who are contemplating how to arrive at the best and most equitable means of addressing flooding.”

Beyond the numbers, says Nicola Ulibarri, assistant professor of urban planning and public policy, “you have to look at who, in fact, is being impacted by these floods. Along with the people from my department, we brought on sociologist David Brady from UC Riverside, who really helped us understand what social vulnerability is. This helped us think about the inequitable impact of floods in a really robust way, from both the engineering and social science sides.

“When we had rough drafts of the models and some initial results,” Ulibarri continues, “I led a series of different focus groups over several months — getting together with policymakers, planners, nonprofit organizations and regulatory agencies – to ask, ‘Does this make sense? Are we answering the right questions with these models?’ We wanted to make sure our work was relevant to the types of decisions that they’re making.”

The inequities in flooding’s impacts are at least as old as the now-crumbling infrastructure that was supposed to protect everyone, says Amir AghaKouchak, professor of civil and environmental engineering.

“You have to look at the discriminatory zoning and redlining that began in the 1930s after the New Deal,” he says. “Areas that were relatively poor and racially segregated received less investment than other areas. Their vulnerability increased over time, and today it’s a major issue because our infrastructure is old and requires attention. That’s not unique to us; this applies everywhere around the U.S. and in other parts of the world.”

One of AghaKouchak’s specialties is studying the effects of compound events. One example, he notes, is that when drought and fire cause deforestation and loss of ground cover, flooding grows more severe.

Just how bad can a 100-year flood be?

The last 100-year event, known as the Great Flood of 1862, was caused by a monthlong storm system that dropped 35 inches of rain, flooding much of California and Oregon and even adjacent states to the east.

California’s state government had to move out of Sacramento because it was underwater for weeks. Huge swaths of Los Angeles County (which then included the future Orange County) were also inundated. Statewide, the flood caused 4,000 deaths (more than 1 percent of the entire population), untold loss and property damage, and the demise of some 400,000 cattle.

If such a storm let loose today, the rain would be landing on a very changed place. In 1862, L.A. County had just over 11,000 residents, less than one-third the number of students currently enrolled at UC Irvine. The L.A./O.C. area now is home to more than 13 million people.

Most of the land then was undeveloped, permeable earth. Now, Sanders notes, “so much of the land has been built out with impervious surfaces like concrete and asphalt that don’t soak up any water.”

Floodwaters today go directly into storm drains, soon joining and overwhelming the concrete channels and rivers, which were designed for speed, not volume. According to Sanders, those arteries would likely be blocked by debris and sediment washed down from hills and mountains robbed of their watershed by drought and fire. Rocks, mud, tree trunks and boulders would crush homes and power lines. Bridges would be destroyed, as well as the viability of highways and trains. The harbors’ cargo ship ports might fill with sediment and be unusable for months or years. The several feet of standing water everywhere would be rank with untreated sewage, oil and toxic industrial chemicals. Many of the homes left standing would fill with mold.

How would UC Irvine fare in such a flood? “The San Joaquin Marsh next to us would be inundated, and the habitat and research ponds would all be underwater — affecting scores of wildlife — but we don’t predict a severe impact on the campus itself,” Sanders says.

Formulating solutions

As groundbreaking as the flood simulation modeling is, Sanders acknowledges that it’s only a first step toward solving the risks it details. He and the others are already working on that.

“The training of an engineer is to go directly to ‘What can we do to fix the problem? How can we innovate? How can we improve? How can we adapt?’” Sanders says. “I think we’re fundamentally wired to take on challenges and improve situations in some way.”

One scenario would be to replace the narrow concrete canyons with sprawling, slow-moving, vegetation-rich natural rivers, “but how many people would buy into creating a kilometerwide river park through downtown Los Angeles all the way to Long Beach?” he asks. “The property values alone of the land that would need to be bought would make that intractable.

“Whatever solution is arrived at, it will necessitate a tremendous amount of adapted infrastructure, which should serve communities even when it’s not flooding, which is most of the time,” Sanders continues. “Drainage systems can be designed so water is collected, treated and made available for drinking water, irrigation or industrial uses. Wetlands can process inorganic nutrients out of floodwaters before they cause problems in the ocean. Parklands can be included to provide shade and cooling during heat waves.”

He and AghaKouchak stress that there is more research to come. One is a project assessing flood risks in the wake of wildfires. A paper is also in the works on the effects of “nuisance flooding,” the smaller events that don’t get headlines but can still disrupt normal life.

In general, Sanders says, “the next step for us is to study solutions to the risks we’ve raised. We will update the model to account for different types of systematic interventions, such as raising levees, investing in green infrastructure and widening channels, and we will study the costs and distribution of benefits for each alternative. We are now in a unique position to not only measure the effectiveness of these measures — such as reductions in the amount of property and number of people exposed to flooding – but also see who benefits from these reductions — and where.”

In December, Petrie-Norris convened a roundtable discussion at UC Irvine to address solutions to coastal erosion. The conversation included Sanders, Ulibarri and Matthew, as well as engineering dean Magnus Egerstedt, social ecology dean Jon Gould and others.

Sanders sees inland flood adaptation as part of the solution to coastal erosion. “The present system is to capture sediment and drag it off to landfills,” he says. “In their original state, Southern California’s rivers carried sediment from the mountains to the coast, where it helped replenish beaches, a huge part of our culture and economy. Whatever flood plan is arrived at, it needs to address that.”

Daniel Kahl, a UC Irvine civil and environmental engineering doctoral student, has worked with Sanders studying sand erosion and helped develop the initial flood modeling design.

In December, Kahl traveled to Munich, where he received an Allianz Climate Risk Award, recognizing young researchers, and presented the flood risk paper, which received considerable interest. One compelling reason is that much of Western Europe just experienced two years of devastating floods, causing deaths and widespread damage.

“In Europe, they have all the information that we’d need to plug into this model and run it,” Kahl says. “Most developed countries probably have what’s needed to run the model at a similar resolution to what we did in L.A. It would be more of a challenge to collect that information in undeveloped countries.”

It’s his generation that’s inheriting this troubled planet, but Kahl’s not particularly daunted by what the future may hold.

“I see it more as an opportunity,” he says. “I see a lot of good discussions and communications between people who are more or less on the same page about finding solutions. The only cause for doom and gloom is when we just don’t acknowledge that there are problems to be solved.”

Daniel Kahl, UC Irvine civil and environmental engineering doctoral student.