Robin Buller, UC San Francisco

Hanna Yakubi sat stunned. On her screen was a marketing plan from the Pain Coalition, a front group — masquerading as a patient advocacy organization — funded by major pharmaceutical companies implicated in the opioid epidemic. In plain language, it laid out high-pressure tactics aimed at getting people to use more pain medication, including one that Yakubi hadn’t seen before: targeting kids.

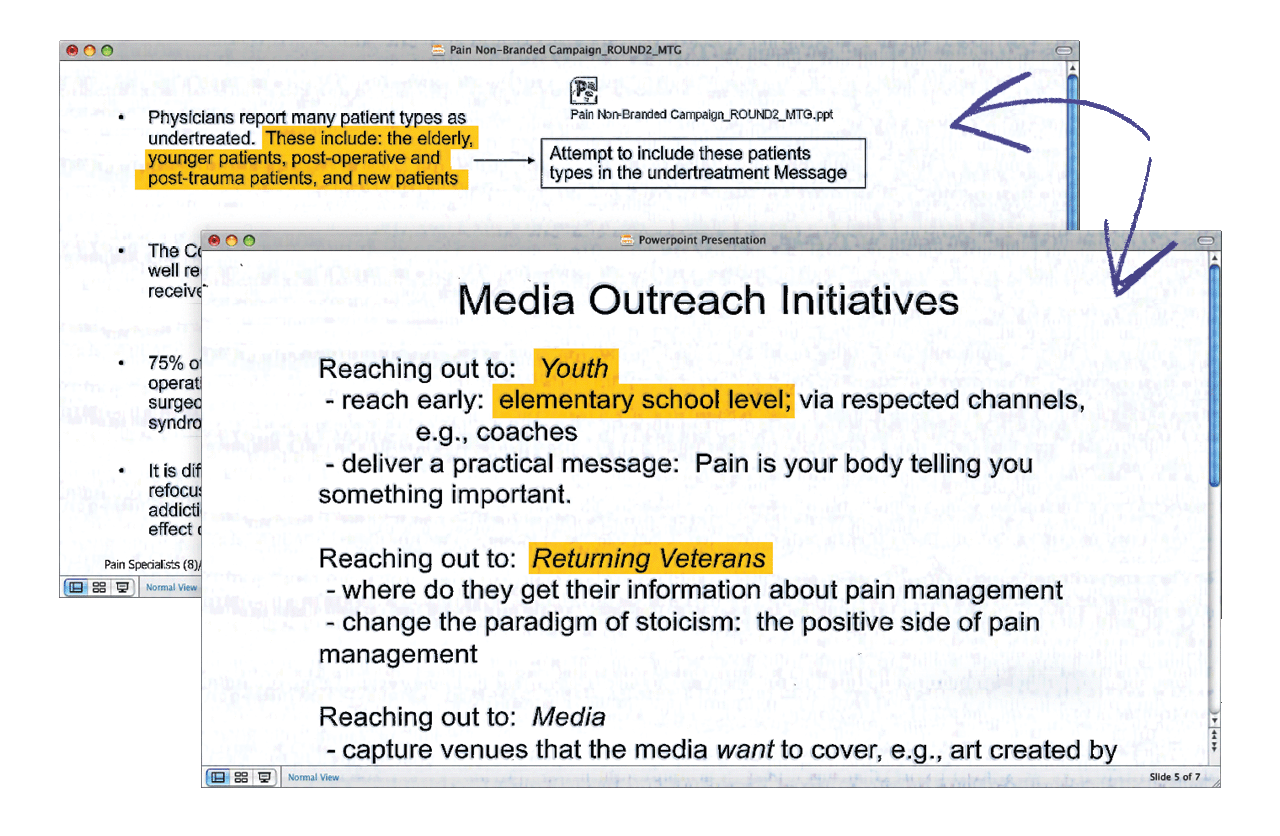

One slide told drug sales reps to reach out to youths “early,” at the “elementary school level,” and to use wording that a 6-year-old could understand: “Pain is your body telling you something important.” Bullet points even suggested that salespeople connect with respected channels, like Little League coaches and school nurses, and essentially turn them into mouthpieces for the merits of medicated relief.

It was March 2020, and while much of the world was hitting pause on work and school, Yakubi and her colleague Brian Gac — then students at the UCSF School of Pharmacy — were sinking their teeth into a nascent subcollection in UCSF’s Industry Documents Library. More specifically, they were sifting through 500 previously unexamined court documents from a landmark case brought by the state of Oklahoma against Johnson & Johnson, Purdue Pharma, and 11 other opioid manufacturers. The case accused the companies of having employed deceptive marketing tactics for opioid products, thereby perpetuating the nationwide opioid crisis. With all the documents available digitally through the UCSF Library, Gac and Yakubi could work virtually and in tandem during the pandemic lockdown.

At the time, most of the trials against opioid drug manufacturers were still underway. Many verdicts had yet to be declared. The Oklahoma case, decided in the state’s favor in 2019, “was one of the first big decisions ever made, even at the state level, and we were able to dig into it,” says Gac, PharmD ’21, now a fellow at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

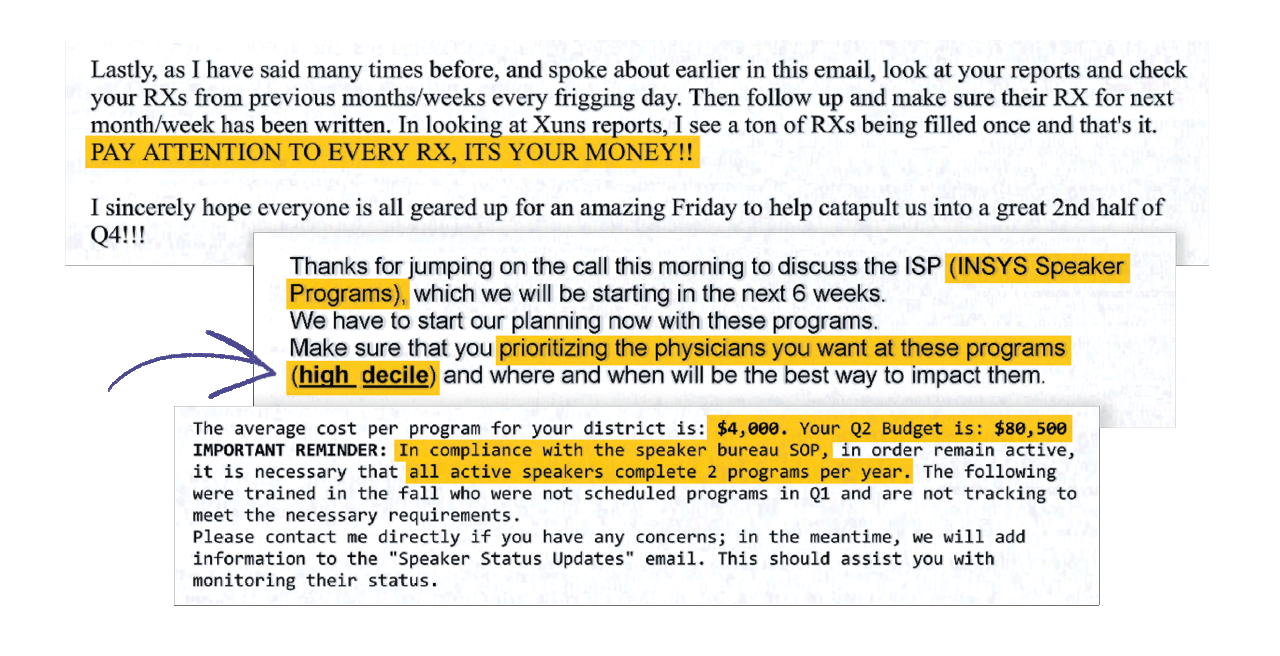

While the document cache was slim, it was rich in information. From emails in which executives floated marketing plans targeting veterans to announcements that incentivized pharmacists to ignore concerns about filling too many opioid prescriptions, the documents laid bare the profit-driven intentions and willful negligence of the opioid industry. They revealed a problem that scholars, politicians, and the general public were just beginning to understand and that has contributed to the death to date of more than 600,000 Americans.

Under the supervision of Dorie Apollonio, PhD, MPP, a professor of clinical pharmacy, Gac and Yakubi went on to publish the first studies of opioid industry practices grounded in materials from the collection, which today boasts more than 3 million documents. Looking back, the two see that they were just scratching the surface of a trove that holds vast scholarly potential for researchers studying topics ranging from the legalization of psychedelics to the appeal that vaping products hold for young people to the power of authority figures in the workplace. “There is an endless supply of information in that archive,” says Yakubi, PharmD ’21, now a resident in oncology pharmacy at UC Davis.

What’s more, the documents present an opportunity to prevent future drug industry injustices by allowing researchers to look at the opioid crisis through the eyes of those at the center of commercial wrongdoings.

From tobacco to opioids, UCSF has a long history of documenting industry practices

Established two decades ago to house millions of documents that surfaced from lawsuits against the tobacco industry, UCSF’s Industry Documents Library is a rich repository of sources that reveal the inner workings of various commercial sectors, including fossil fuels, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and food. Research into the tobacco files, much of it led by UCSF’s Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, has provided unprecedented insight into that industry’s cynical tactics and helped foment sweeping changes in tobacco laws. Additional studies have exposed troubling practices in other industries as well.

It was an opportunity to work in the tobacco archives that first brought Apollonio to UCSF as an American Legacy Foundation postdoc two decades ago. As a master’s student at Harvard, she had researched syringe exchange programs, and as a doctoral student at UC Berkeley, she had studied tobacco industry lobbying. Since joining the School of Pharmacy faculty in 2006, she has investigated topics ranging from the way the sugar industry obscured the health dangers of sucrose to how the use of tobacco and recreational cannabis products overlap. “My interest in substance use goes way, way back,” Apollonio says.

Through her research, she developed deep relationships with the archivists at the helm of the Industry Documents Library, who first encouraged her to dig into their holdings from the drug industry five years ago. At the time, the materials had received little scholarly attention.

But Apollonio needed students to help, and most showed little interest in documents research — a field that is just now gaining traction in pharmacy. As she was about to give up, Gac and Yakubi walked into her office and were instantly enthralled with the idea. “It was a miracle of timing,” she says.

Pharmacy students make disturbing discoveries

Gac and Yakubi could barely contain their excitement when Apollonio first suggested that they explore the internal communications of some of the biggest players of the pharmaceutical industry — and biggest culprits in the opioid epidemic. “If I don’t do this project now, I may never have an opportunity like it outside of pharmacy school,” Yakubi recalls thinking.

Apollonio’s decades of experience in the tobacco archives gave the team a running start. Gac and Yakubi moved through the files quickly — in part because they weren’t doing much of anything else during the pandemic lockdown, but also because the material was so captivating. Working methodically, they identified core themes, such as how companies sought to target children and other vulnerable groups, manipulate statistics, and downplay opioids’ addictive properties.

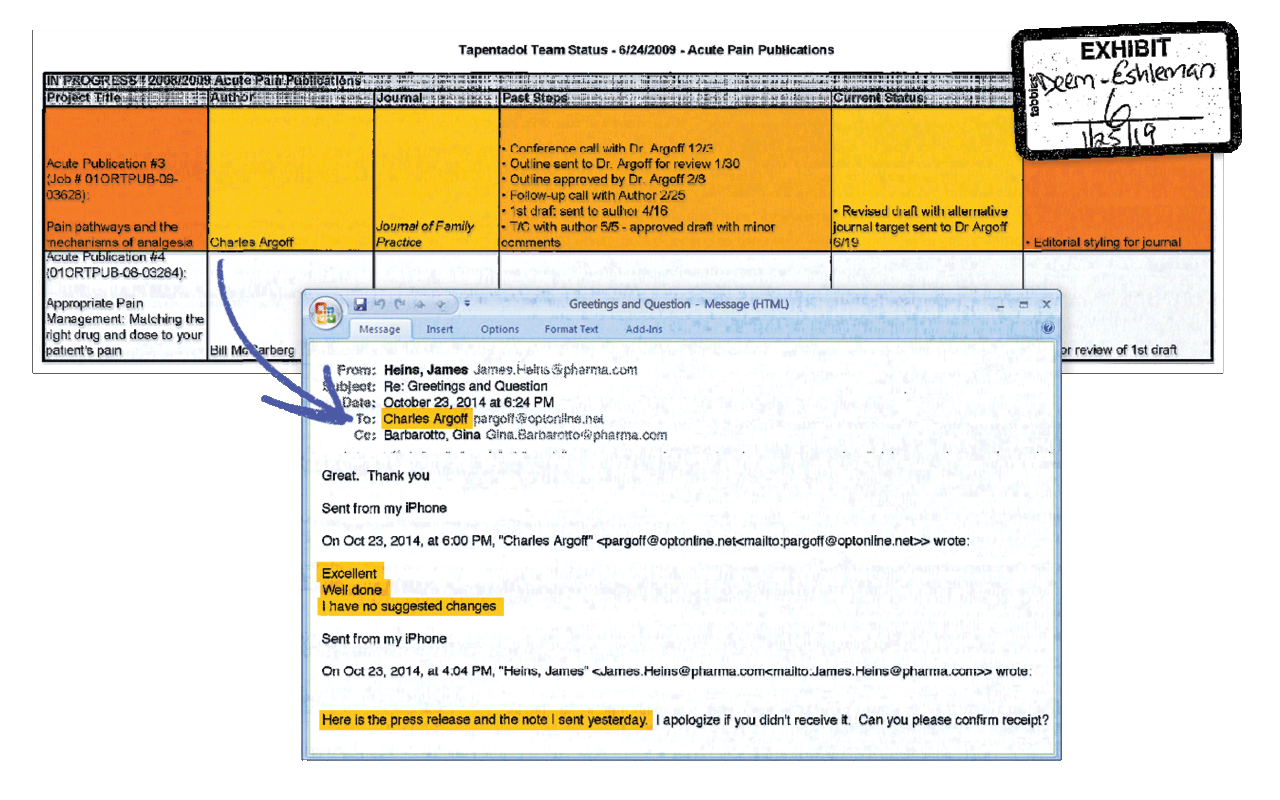

They found, for instance, that Johnson & Johnson actively used ghostwriters to write academic papers that both overstated the efficacy of opioids and downplayed their addictive properties. In fact, the company designed studies and drafted entire journal manuscripts internally before sending the papers to scholars who were later named as primary authors. Often, those individuals were prominent professors who received sizable consulting fees in exchange for the use of their names.

In another example, a social media networking site called “Growing Pains,” which was funded by Janssen and Medtronic, seemed to the researchers designed to market prescriptions to teens with chronic pain.

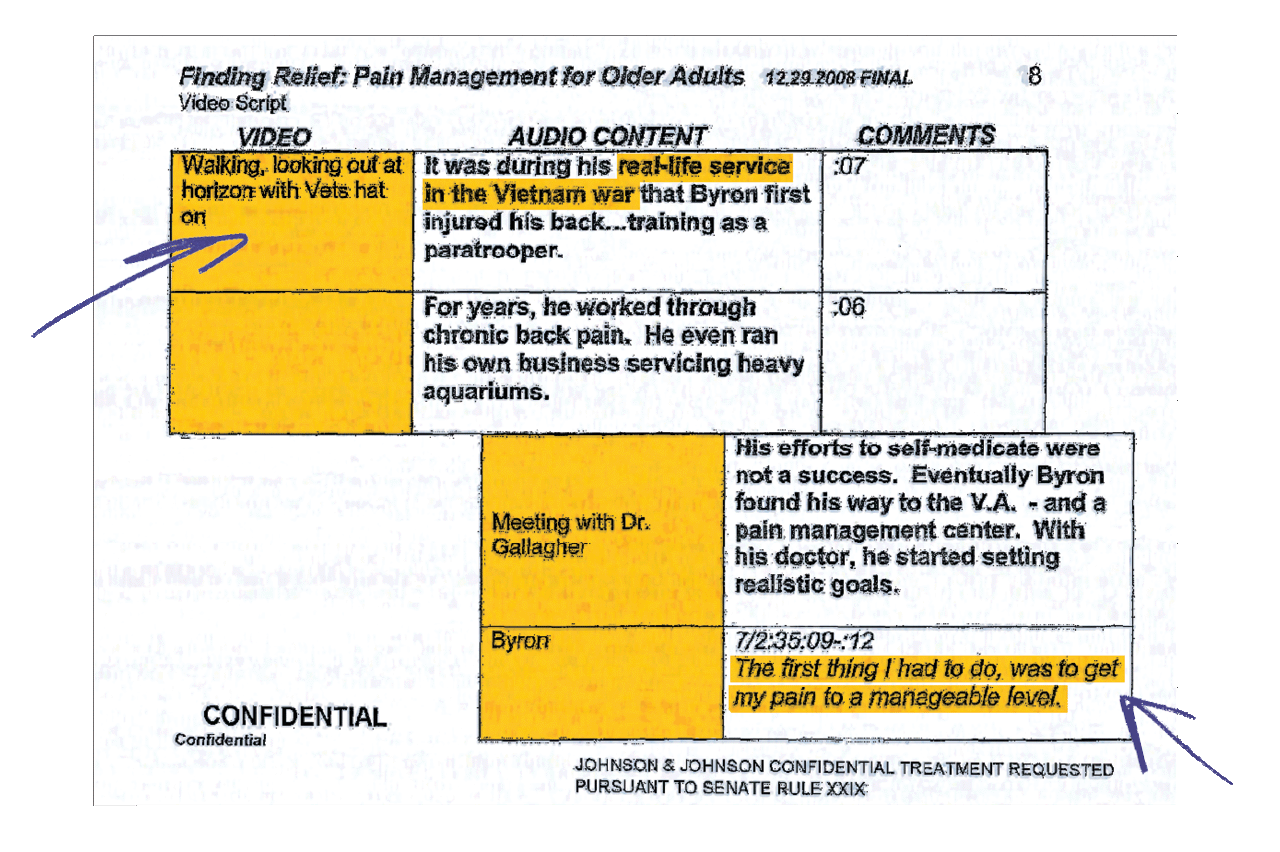

Both students can recall key moments, as they sorted through the files, when they made disturbing discoveries. For Gac, it was reading the internal marketing plan for OxyContin and realizing that executives had pulled not only sales strategies but also slogans directly from Big Tobacco. For her part, Yakubi was astounded by emails revealing that companies had targeted Afghan war veterans, a group that is already at high risk for substance misuse. Leaning into the population’s emotional vulnerability, marketing executives sought to make veterans and their physicians believe that opioids were the only recourse to treat trauma.

Federal agencies like the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense were identified as “strategic customer segments” by Janssen. Executives from Purdue Pharma lobbied for federal legislation like the Military Pain Care Act of 2008, which called for all active military personnel, veterans, and their dependents to be preemptively and regularly assessed for pain. And slides from a 2012 Janssen training program encouraged public relations specialists to use slogans like “those who have served, need to be served” as a means of encouraging doctors to prescribe more opioids to veterans coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan.

“That one bothered me because my parents were affected by the war in Afghanistan,” says Yakubi, who is the child of Afghan refugees. “I could see that kind of methodology working so efficiently within my community, as well.”

A large part of what made the marketing techniques so problematic was that many campaigns were unbranded, meaning it wasn’t always clear that companies — which stood to profit from sales — had paid for the endorsements. Plans for a 2008 unbranded campaign orchestrated by Janssen said outright that the ideal outcome of the initiative would be for primary care providers to “state that they will be more aggressive in their treatment and use more opioids.”

Even Apollonio, who had made her fair share of startling discoveries over the years, remembers leaving meetings with Yakubi and Gac feeling aghast. “I’ve read industry documents for a long time, and I should stop being shocked,” she says, “but I always end up finding a moment where I’m still shocked by what someone has written down.”

Setting the stage for a burgeoning new field

Before long, the team realized they were looking at enough material to produce more than one — possibly as many as three or four — substantial academic papers. Those publications laid the groundwork for Apollonio’s next group of students.

Using Gac and Yakubi’s work as a model, four current third-year pharmacy students, including Clever Chiu and James Chhen, dove into a case involving the national pharmacy chain Walgreens. Focusing on specific retail spaces enabled them to ask new questions, like what role distribution centers might have played in enabling the opioid crisis, and whether issues of negligence spanned the entire company or were specific to individual stores.

Chiu was struck by what the documents revealed about the behavior of individual store managers in response to company incentives that rewarded teams for distributing more opioids. “Store managers were giving bonuses to pharmacists who were filling more prescriptions,” he says, meaning the pharmacists had little motivation to flag problematic patterns of substance use.

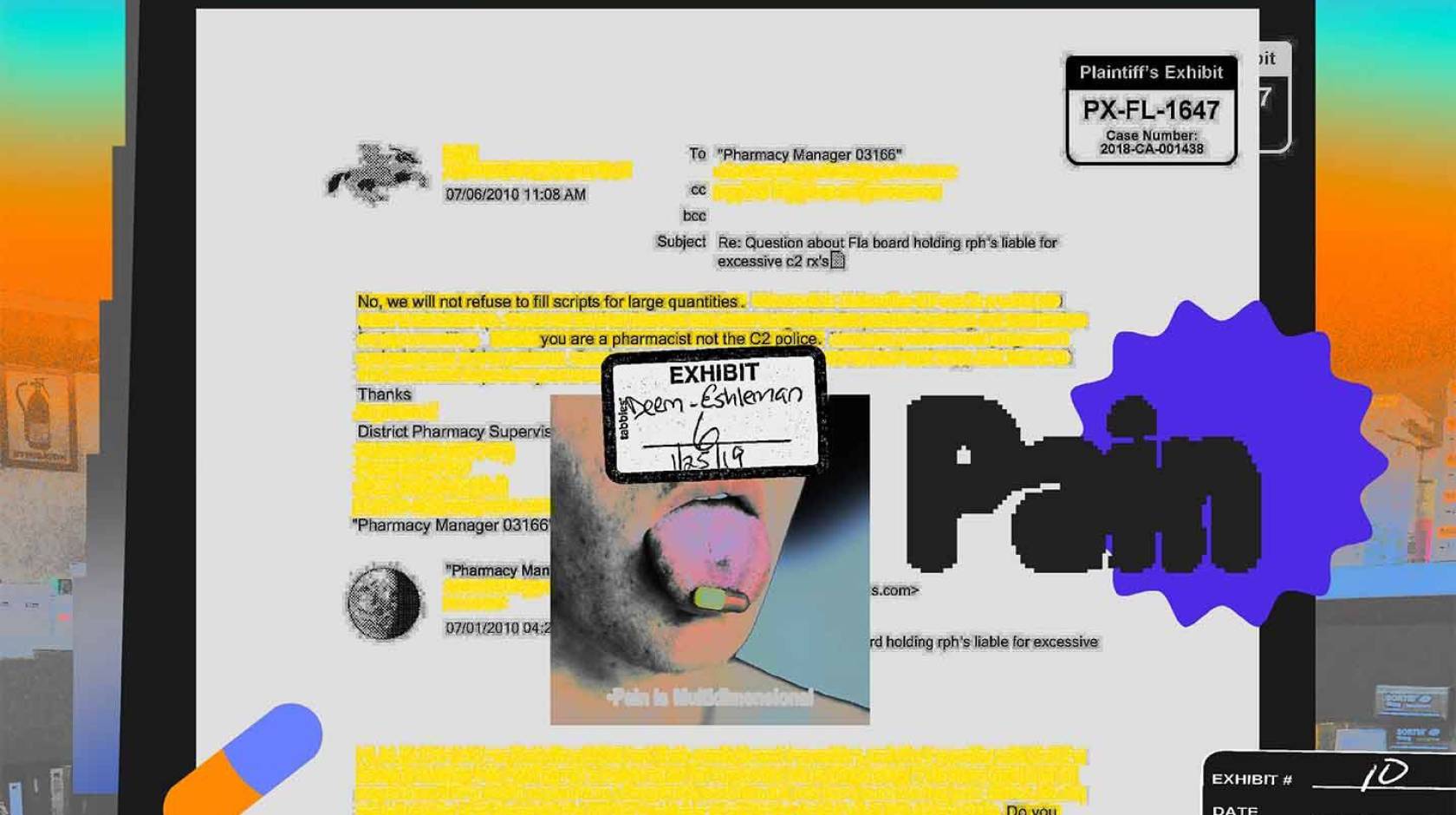

In fact, the group found that pharmacists would be singled out and subjected to disciplinary action for raising suspicions. In internal complaint filings, a Walgreens corporate employee firmly reprimanded a pharmacist after she raised concerns about the quantities of opioids prescribed by her store. “No, we will not refuse to fill scripts for large quantities,” the email read. “You are a pharmacist not the C2 [narcotics] police.”

Chiu was floored: “I was just like, ‘Wow, I can’t believe they’re writing these things.’”

A document pipeline opens

Since Gac and Yakubi first dove into the 500 documents in March 2020, the archive has veritably exploded in content and use. In 2021, the UCSF Library forged a partnership with Johns Hopkins University (JHU) to help manage and facilitate engagement with the Opioid Industry Documents Archive (OIDA), which is now its own entity. “We’ve had a lot more help,” says Rachel Taketa, MLIS, of the collaboration; a processing and reference archivist at UCSF, she has worked closely with Apollonio and her students.

Recently, Kate Tasker, MLIS, director of the Industry Documents Library, and Caleb Alexander, M.D., M.S., a professor of epidemiology and of medicine and the OIDA lead at JHU, led the charge to collect materials from numerous opioid settlements that have taken place around the country. They’ve reached out to attorneys general in Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, and other states to ensure that documents are properly preserved.

“Sometimes, internal company documents that are turned over during the discovery phase of lawsuits become public, but historically, the vast majority either go back to the company, get shredded ... or get deleted,” explains Tasker. “So it’s really significant for these discovery documents to be made public.”

“I guess efforts to get documents to go public finally reached the right ears,” says a relieved Taketa, who also credits Stanton Glantz, Ph.D., the retired UCSF professor seen by many as the founder of the tobacco industry archives, with having written an influential op-ed about the public’s right to know the contents of settlement disclosures.

Thousands of new files are added to OIDA every month, and another 10 million or more may be coming down the pipeline. With every new acquisition, the UCSF and JHU team must diligently comb through each file to ensure that sensitive information is redacted and that the documents are thoughtfully organized. The library recently won a prestigious award for those efforts. “This isn’t just a WikiLeaks-style project where we’re...throwing documents on the internet,” says Tasker.

She and her JHU colleagues hope that such a wealth of untapped information will draw in new researchers – including from beyond the walls of their own institutions.

Enticing research possibilities, in academia and beyond

The archive has limits, of course. It reflects only internal industry perspectives, for instance, and some material remains inaccessible because of privacy concerns. “I’d be cautious using opioid industry documents exclusively,” says Apollonio. But its takeaways, the researchers say, are invaluable.

Scholars of law and business as well as medicine may gain insights from the material. From questions of legal liability to duties of care to ethical shipping and distribution practices, the range of topics reflected in the archive is vast. “Industry malpractice didn’t start with drugs,” and it won’t end with them, Gac says, pointing to other sectors that have engaged in harmful marketing tactics, like the food, firearms, and social media industries. Beyond academia, journalists and filmmakers have also found the collections fruitful. Their work has increased the public’s awareness of how major companies, like the consulting firm McKinsey, helped to bolster opioid marketing. It has also spotlighted how hundreds of thousands of Americans turned to street drugs when doctors reduced or discontinued their opioid prescriptions in response to the overuse crisis.

For pharmacists, the repository’s contents teach the importance of care and diligence. “The archive has given me a better understanding of the true clinical utility of drugs,” says Yakubi, emphasizing that opioids can and do play an important role in treating pain. Today, Yakubi works with cancer patients, whose need for opioids is undisputed. “We use opioids a lot, but we use them appropriately,” she says. To her, that makes the manipulative tactics on display in the documents that much more nefarious.

Chhen walked away with a new appreciation for the many roles that individuals and groups can play in perpetuating a public health crisis at ground level. “The opioid crisis was multi-factorial,” he says. “It involved a whole group of organizations.”

But there is still more work to be done to prevent future addiction epidemics, says Apollonio – especially on the regulatory side. “They are not doing the job that people hoped that they would do,” she says of laws that predate the opioid epidemic and that penalize unbranded campaigns and other dangerous marketing tactics. “They’ve been kind of a blunt instrument. There’s absolutely no reason that another addictive medication isn’t going to have the same kind of trajectory in the future.”

That’s where internal documents research can be a valuable tool that can lead to meaningful change and help prevent future catastrophes, she hopes. By learning where opioid industry insiders took wrong turns, researchers can help to expose gaps in drug policies, as well as ways in which additional regulatory oversight may be beneficial. As a result, the drug industry might be better positioned to prioritize patient well-being over profits.

“How do you keep them from marketing in problematic ways while still making medications accessible to people?” Apollonio asks.

Going forward, that search for balance — one that appreciates the dangers of deceptive marketing tactics, as well as the fact that pharmaceuticals save lives — will serve as her guide.