Samuel Banister, Axel Adams and Roy Gerona, Stanford and UCSF via The Conversation

In March and April, 56 people in the Sacramento area were hospitalized after taking Norco brand hydrocodone pills. Fifteen died.

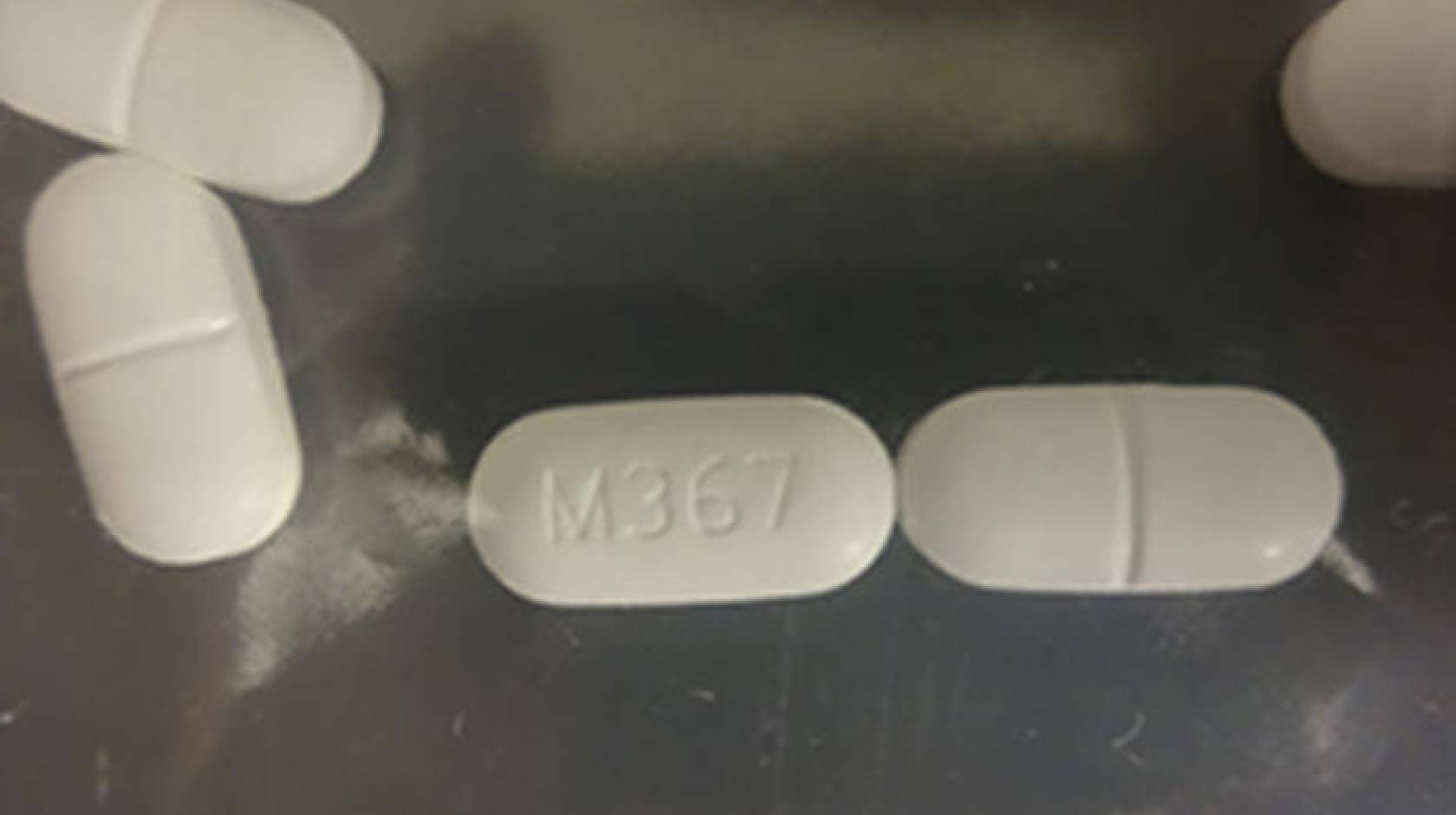

But, as we discovered, these pills were not pharmaceutical hydrocodone at all. They were counterfeits containing fentanyl that were purchased on the street. Fentanyl is an opioid far more powerful than hydrocodone. Counterfeit pills containing fentanyl were also found in Prince’s home.

While fentanyl made by pharmaceutical companies is sometimes diverted to the black market, since 2013 the distribution of illicitly manufactured fentanyl has risen to unprecedented levels.

These illicitly made substances are generally formulated to look like other drugs – heroin or oxycodone tablets. This means that users may not be aware they are taking fentanyl or another synthetic opioid. For instance, our work at the Clinical Toxicology and Environmental Biomonitoring Laboratory at UCSF has identified counterfeit Norco containing fentanyl and a new synthetic opioid that is chemically unrelated to anything used in medicine. Fentanyl has also been found in counterfeit Xanax, an anti-anxiety drug.

We study the pharmacology and toxicology of new psychoactive substances (NPS). These entirely synthetic, illicitly made “designer drugs” are designed to work on the same receptors in the body as drugs like marijuana, methamphetamine or heroin. The adulteration of counterfeit pharmaceuticals and street drugs with synthetic opioids is arguably the most worrying new trend in our field.

Credit: Damir Sagolj/Reuters

What are synthetic opioids?

When we talk about opioids, we are referring to a class of chemicals. They differ in form and potency, but they all interact with opioid receptors in the body, producing painkilling and euphoric effects.

Opioids include naturally occurring drugs that are extracted from the opium poppy plant, like morphine. They also include semi-synthetic drugs that are also derived from poppy but then chemically manipulated, such as heroin. The most potent opioid drugs, however, are entirely synthetic chemicals that look nothing like those produced by nature, like fentanyl.

Fentanyl acts on opioid receptors, which are found throughout the body, with about 50-100 times the potency of morphine. The drug also has important medical applications. In fact, if you’ve ever had surgery, you’ve probably had fentanyl. But, as with any opioid, it can be dangerous when it is misused.

Fentanyl, often called “China White” on the street, has historically been sold as a heroin substitute because it is incredibly potent, entirely synthetic and cheap to manufacture. One kilogram of illicit fentanyl can be purchased from China for US$3,000-$5,000 and turned into millions of doses of “China White.” Instead of diverting pharmaceutical fentanyl, or other potent synthetic opioids with medical or veterinary applications, clandestine labs can just manufacture their own.

For instance, carfentanil, a form of fentanyl used as a veterinary tranquilizer for large animals such as elephants, was found in heroin last month in Ohio. At least one overdose death already has been reported.

Carfentanil is 100 times more potent than fentanyl itself, and 10,000 times more potent than heroin. It is estimated to be active in humans at doses as low as one microgram, one millionth of a gram. The estimated lethal dose of fentanyl is about 2 milligrams per person, but the lethal dose for carfentanil in humans is unknown. Based on data from chimpanzees, it is estimated to be in the microgram range. To put that in perspective, a grain of sugar weighs about 600 micrograms.

In 2015, the aggregate U.S. production of carfentanil for veterinary use just 19 grams. That suggests that the carfentanil found in heroin was made in an illicit lab, rather than being diverted.

And Canadian police just intercepted a package from China containing 1 kilogram of carfentanil, enough for 50,000,000 potential overdoses.

Hard for the feds to keep up with the labs

In March, the DEA arrested four men in California found formulating acetyl fentanyl into counterfeit pills. That same month, law enforcement officers in Ohio seized 500 counterfeit oxycodone pills that were found to contain the synthetic opioid U-47700. Seizures of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids destined for the U.S. increased from just eight pounds in 2014 to 200 pounds in 2015.

That same year, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration reported more than 13,000 seizures of fentanyl, a 1,900 percent spike since 2012. While more synthetic opioids are making their way from the lab to the street, banning these drugs can be hard.

Pharmaceutical fentanyl is regulated as a Schedule II controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act. This category is for drugs that have a high potential for abuse but also have recognized medical uses.

The DEA has identified at least 15 illicit fentanyl analogues in the U.S. in the past few years, adding many of them to the most restrictive regulatory category of the Controlled Substances Act: Schedule I. These include acetylfentanyl, which caused more than 60 fatal overdoses in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania in 2013, and butyrylfentanyl, which was responsible for 38 deaths in New York in 2015.

Another synthetic opioid, AH-7921, was recently banned after it was linked to overdoses. It, too, is a synthetic opioid chemically unrelated to fentanyl or any opioid used in medicine, but it acts on the same opioid receptors as fentanyl. And it’s just one of the chemically distinct synthetic opioids which have been linked to overdose deaths.

The DEA has the power to prosecute crimes involving synthetic opioids that are not explicitly scheduled by invoking the Federal Analogue Act, but it can take a long time to get drugs onto Schedule I.

Under the act a new synthetic opioid drug must be shown to be “substantially similar” to a Schedule I opioid before it can be prohibited. The broad, vague language of the Federal Analogue Act means that similarity is easy to claim, but must be proven in court, which can be a slow process.

The trouble is that as individual illicit synthetic opioids are added to Schedule I, clandestine chemists in China and Mexico “tweak” molecular structures to circumvent the law by creating new drugs with similar effects. Some of these new opioids don’t even chemically resemble morphine, heroin or fentanyl – they just activate the same opioid receptors in the body. This is a trend we have seen before with synthetic stimulants sold as “bath salts” and with synthetic cannabinoids sold as “Spice” products.

A repeat and deadly performance

The first synthetic opioid overdose epidemic killed more than a dozen people in the U.S. in the late 1980s, and was due to 3-methylfentanyl, an opioid “designer drug” at least 300 times more potent than street heroin. The last major fentanyl outbreak in 2006 caused the death of more than 1,000 heroin users and was traced to a single production facility in Toluca, Mexico.

As Dr. Gary Henderson stated when he defined the term “designer drug” in 1988 after the first synthetic opioid outbreak:

“The ‘Designer Drug’ problem may become an international problem. A single gram of any very potent drug … could be synthesized at one location, transported to distribution sites worldwide, and then formulated (cut) into many thousand, perhaps a million, doses. Preventing the distribution of such small amounts of the pure drug will be exceedingly difficult.”

Dr. Henderson was eerily prescient about the current situation. He just underestimated the scale of the problem.

Samuel Banister is a research fellow at Stanford University. Axel Adams is a medical student and master's candidate in public health at UCSF. Roy Gerona is an assistant professor at UCSF.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.