Stephen P Wampler, Lawrence Livermore Lab

There has long been a concern among civil engineers that dams could fail days or weeks after an earthquake, even if no immediate evidence of a problem surfaced.

Their concern has focused on possible cracks at the interface between the concrete section of a dam and the soil embankments at the dam's sides, and on how the soil filters nestled amidst the embankments would fare.

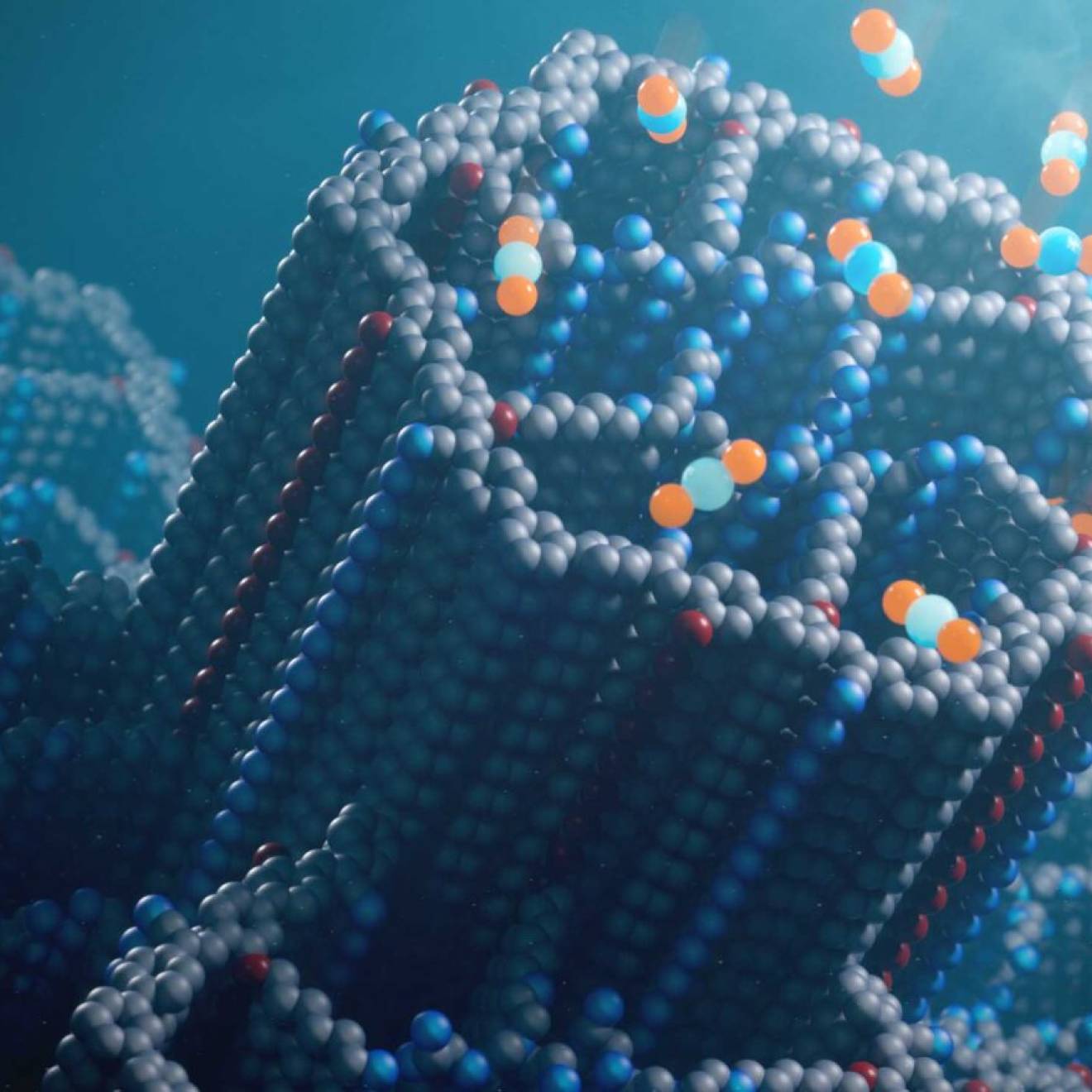

Soil filters consist of coarser grain soils than the soil used in the dam's impervious core, and their purpose in the event of a crack in the soil, is to prevent the finer core soil particles from rapidly eroding and flushing through the filter. This helps reduce the flow of water, preventing the dam's catastrophic failure. Soil filters have been incorporated into dams for more than five decades.

Since soil filters were instituted, their design standards have been based on experimental studies without detailed and validated computer modeling of the soil grains — until now.

For the first time, under a collaboration between Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC), researchers have completed a study demonstrating the effectiveness of soil filters at the soil grain scale.

From erosion to dam behavior

Their work involved conducting three-dimensional modeling of soil filters at the grain level and then bridging the interaction of soil erosion to the behavior of the dam itself, said LLNL mechanical engineer Lee Glascoe.

"Researchers in the past have looked at dam-scale models using experiment-based assumptions about grain-scale behavior," Glascoe said. "We modeled the grain scale and pushed our assumptions back to first principles.

"We believe we have helped to put to rest one of the major concerns among dam engineers — are the soil filter standards that have been the design criteria for dams valid for earthquakes? The answer is 'yes,' if they are consistent with the current design standards," Glascoe explained.

While Glascoe headed the Livermore team, the researchers from the ERDC team in Vicksburg, Mississippi, were led by structural engineers Stan Woodson and Robert Hall.

Funded by the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate, the project focused on validating LLNL's advanced high performance computer simulations of soil erosion and transport to detailed experimental centrifuge and soil erosion tests by the ERDC.

The collaboration's computer simulations, validated by experimental tests run by the ERDC, show that the dam filters that meet today's existing standards for reservoirs are effective for protection.

Furthermore, the computer simulations can be used to assess filter success or failure under different soil or loading conditions and can lead to meaningful estimates of the timing and nature of major dam problems caused by internal erosion from the core through the filter materials.

"The Laboratory's computer simulations and the physical experiments performed by the ERDC compared very favorably," Glascoe stated.

Mary Ellen Hynes, the senior engineering adviser of the DHS Science and Technology Directorate's infrastructure protection and resilience programs, said the team's effort represents a "superb body of research."

"For decades, we have wanted to be able to numerically model the transport of particles through filter zones to test against our empirical data. This collaboration has given us the information we needed," Hynes added.

Successful collaboration

One of the team's major findings, according to Hall, is the development of initial computational tools to predict how the interface between a dam's concrete section and embankment sections with the sections' filters will behave during earthquakes and other severe events.

ERDC geotechnical and structural engineers ran experiments at their facility's Centrifuge Research Center, the world's most powerful centrifuge, using a one-foot-high model dam that was subjected to 30 times the force of gravity.

"We tried to scale the structure, as if we had a 30-foot dam," Hall said.

In a follow-on experiment, they utilized larger glass beads, at about 1,500 microns, to simulate the soil filters, and smaller beads at 350 and 50 microns to serve as the impervious clay core materials, with normal water flows and high pressure water flows.

"The whole purpose of the ERDC's work was for us to conduct the correct experiments to generate data that could be used to validate the numerical tools or computer simulations of LLNL," Hall said.

Glascoe called the three-year joint project one of the best collaborations he's ever been involved in.

"It leveraged the inherent strengths of both laboratories: the ERDC being the engineering lab with the experimental expertise and LLNL bringing the ability to develop and apply high-fidelity numerical simulations," he said.

"We wouldn't have been able to solve this problem by ourselves. Without the ERDC's experimental validation of our models we could have easily drifted into a theoretical and numerical 'sand box.' The ERDC engineers helped to ground us in the reality and needs of the dam engineering community," Glascoe added.

For the future, Glascoe said that the team would like to use computer simulations to make soil filters more effective and better understand the timing and nature of possible full-scale dam failures caused by erosion.

Beyond Glascoe, other LLNL researchers who worked on the collaboration were geophysicists Yuliya Kanarska, Ilya Lomov and Tarabay Antoun, and geotechnical engineer Souheil Ezzedine.

In addition to Hall, the ERDC researchers also included Woodson, who served as the joint team's DHS program manager; physical scientist David Perkey, and civil engineers Jarrell Smith and Duncan Bryant.

The collaborative research program was managed by John Fortune, the branch chief of the resilient systems division within the DHS Science and Technology Directorate.