Tamra Burns Loeb, Alicia Morehead-Gee and Derek Novacek, UCLA via The Conversation

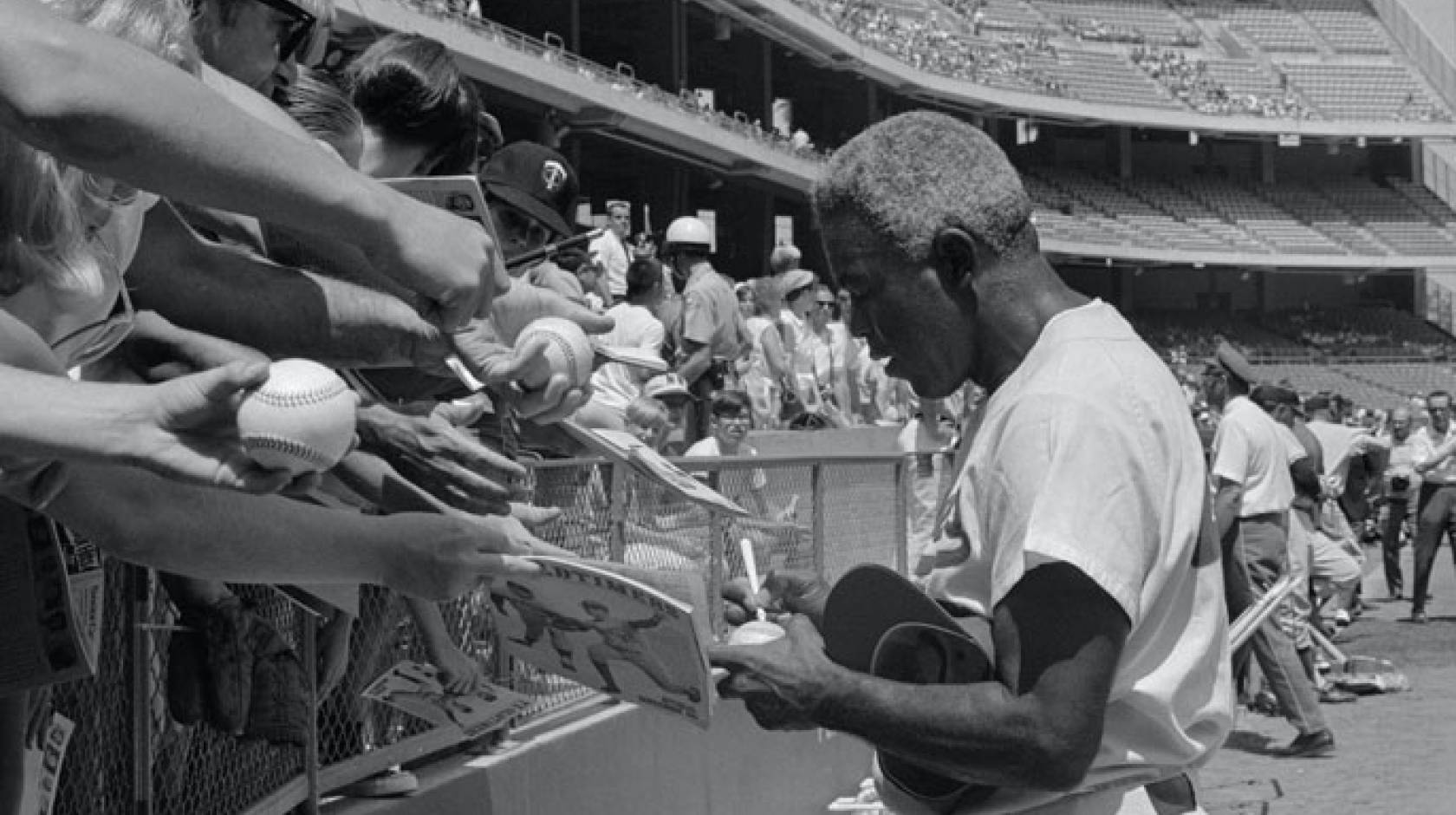

Baseball great Jackie Robinson was a living, breathing example of athleticism and apparent good health, playing four sports at UCLA and becoming the first Black man to play in major league baseball.

And yet, the athletic hero and civil rights champion died at age 53, almost blind, from a heart attack, with underlying diabetes and associated complications.

When Robinson died on Oct. 24, 1972, few researchers studied health disparities. There was little understanding that social factors and stress greatly affect health, and that racism and discrimination contribute to poor health outcomes among communities of color. Fewer people paid attention to racial and ethnic gaps in life expectancy.

Since Robinson’s death, however, research has shown that enduring structural and everyday racism can have serious negative consequences for health.

We are researchers who examine mental and physical health disparities in marginalized populations. We can’t help but wonder: Did racism kill Jackie Robinson? And might his life — and early death — help people understand the mechanisms behind how racism kills?

Credit: Rogers Photo Archive

Jackie the hero

Robinson was born Jan. 31, 1919, in Cairo, Georgia, a small town not far from the Florida-Georgia line. Robinson’s father, a sharecropper, abandoned the family when Robinson was a baby. His mother, a housekeeper, moved her five children to Pasadena, California to be near her brother.

Robinson went to Pasadena Junior College and later to UCLA, where he became the school’s first four-letter athlete. His wife, Rachel, would later say he was a “big man on campus.” Yet the big man was not destined to be a graduate; he had to drop out of college due to lack of finances.

Jim Crow still had control in much of the country, but in Brooklyn, Branch Rickey, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, believed it was time to integrate baseball. In 1946, Rickey signed Robinson to play for the Montreal Royals, a Dodgers farm team. Robinson was a star, and Rickey called him up. In 1947, at age 28, Robinson became the first Black American to play in the majors.

Robinson was Rickey’s choice not only because of Robinson’s prowess on the diamond but also because of his strength of character off the field. Yet Rickey warned him it would not be easy. Robinson would be insulted and reviled, Rickey told him, but Robinson could not speak out. He would have to endure whatever insults came his way.

They weren’t just verbal. Some players intentionally slid into his legs with their cleats. He had to have metal plates sewn into his cap to protect him from “beanballs” — pitches intentionally aimed at a batter’s head. Fastballs hurled from the arm of a major league pitcher can be traumatic and result in concussions, broken bones, severe bruising or death.

And always, there were racial slurs.

One of the worst incidents happened when the Philadelphia Phillies came to Ebbets Field to face the Dodgers in Brooklyn in 1947.

Robinson later wrote about that day, recalling some of the insults and taunts. They were not only from fans but from Phillies players.

Robinson also wrote that he considered giving up and tearing into the Phillies’ dugout.

Instead, he went on to win Rookie of the Year in 1947. In 1949, he was National League MVP. He led the Dodgers to a World Series Title in 1955.

Credit: Educational Video Group

Broken records, broken health

Robinson’s health problems began while he was still in the major leagues. He struggled with his weight, and he experienced pain in his knees, arm and ankles. He was diagnosed with diabetes at age 37, about the time he retired. Two of his brothers also had diabetes. Robinson’s hair began to turn white.

By 1969, at age 50, he had nerve and artery damage in his legs. In 1970, he suffered two mild strokes. His doctors noted that both of his legs would soon require amputation. He then lost sight in one eye and experienced limited vision in the other. He suffered from high blood pressure, and had three heart attacks, the third of which was fatal.

However, despite these problems, Robinson kept his diabetes “in the closet,” insisting that he felt good.

A not-so-grand slam of factors

Those of us who study health disparities now have a better understanding how Jackie’s life experiences all likely contributed to his early death. His refusal to capitulate to the hatred he encountered on a daily basis, the magnitude of his role in the struggle to challenge Jim Crow and integrate baseball, and the extensive racial trauma all likely played a factor. In addition, the death of his eldest son, Jackie Robinson Jr., in a car crash in 1971 no doubt took its toll.

It is now well established that the racism and discrimination that people of color experience has a negative effect on health. This burden was incalculably magnified by a society that refused to acknowledge, denied the existence of and justified structural racism. For instance, in 2016, the city of Philadelphia issued an official apology for the racist incidents Robinson encountered there in 1947. Yet efforts to make amends could be offered only to his widow — Jackie didn’t live long enough to receive them.

Environmental conditions that influence health, referred to as the social determinants of health, are driven by structural racism. Many of the social determinants lead to poor health outcomes. These include the conditions in which people are born, live, play, work and age. Racism and poverty/socioeconomic disadvantage are two social determinants that contribute to worse health outcomes in the U.S.

Robinson and his four siblings were raised by their mother after their father abandoned the family when Robinson was an infant. His mother worked long hours as a housekeeper. The Robinsons encountered racism as a Black family in a mostly white neighborhood, and they endured name-calling and taunts from neighbors, who summoned the police to their home without reason.

These traumatic events, including being abandoned by a parent and enduring verbal or physical abuse from others, are known as adverse childhood experiences, or ACES. ACES and other lifetime adversities can have negative effects on one’s health as an adult, leading to higher risk of conditions like depression and heart disease. Robinson’s childhood and adolescence increased his risk for poor health later in life.

Researchers have identified collective coping as as one of the key strategies Black Americans use to deal with racism-related stress. But Robinson did not have access to collective support from other Black baseball players until MLB teams slowly began signing Black athletes months after his debut with the Dodgers. He was carrying the burden alone, except for the support of his wife and Rickey, until other Black players were hired and Dodgers began openly supporting him.

Credit: pianopappy

Before the ballpark

Though Robinson’s illnesses were diagnosed in early adulthood, they could have had their roots in childhood. Adverse social and physical conditions as well as limited access to and poor quality of health care serve as barriers to illness prevention and treatment, limiting the ability to protect one’s health. Experiences of racial trauma and discrimination like those Robinson experienced are linked to smoking, unhealthy eating habits and alcohol use, decreased trust in health care providers, increased cardiovascular risks and negative cardiovascular outcomes.

Experiences of racism and discrimination are painful, sometimes daily, occurrences for many people of color. These include things like being followed in stores, receiving poor service in restaurants and being stopped by police.

We know that Robinson’s experience in the majors was not his first exposure to racism and discrimination. As a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, he sat next to a fellow officer’s wife on a bus at the Fort Hood, Texas base in July 1944. The woman was Black; however, her skin color was light. The bus driver was not pleased. He told Robinson to move to the back of the bus. Robinson refused. Robinson was shackled, arrested and court-martialed. Robinson later was acquitted and given an honorable discharge.

Over time, these repeated stressful episodes can lead to cardiovascular disease by increasing what is called allostatic load. When a person repeatedly experiences the stress of racism, high levels of the stress hormone cortisol are released in the body. Elevated cortisol can lead to high levels of blood sugar, as seen in diabetes, and high blood pressure. Robinson had both diabetes and high blood pressure after years of enduring what was likely a high allostatic load.

Some researchers believe allostatic load may be one reason why high blood pressure is more prevalent and more severe among Black Americans than White Americans.

The reasons for worse health among Black individuals goes beyond physiological responses to racism — it can be racism itself. Black patients also receive less frequent and poorer-quality health care than whites, even when severity of disease, quality of insurance, occupational status and level of education are controlled for.

Racism is even more likely to affect mental health than physical health, but it’s impossible to know how the racism that Robinson experienced affected his mental well-being. Racism is associated with negative impacts on mental health including depression, stress, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal thoughts and alcohol use. In fact, mental and physical health are connected. Poor mental health can negatively affect the way the body responds to stress, and increase inflammation that can increase risks for diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and cancer.

Credit: Bettman/Getty Images

A new day?

How much has changed for Black baseball players since Robinson’s time? As of June 2020, approximately 8 percent of players and one owner in major league baseball were Black, making it difficult to challenge the very system that discriminates against them. However, contemporary players including Jason Heyward and Dominic Smith have described the pervasiveness of systemic racism in American society and their profession, and the importance of raising awareness of its pernicious effects.

In 2020, more than 150 Black former and current baseball players created The Players Alliance to use their “collective voice and platform to create increased opportunities for the Black community in every aspect of our game and beyond.” It seems that what is changing is the refusal to remain quiet, to be stoic in the face of racism and discrimination, both on the field and off.

As Smith noted on Twitter, “Silence kills.” Just as diabetes and hypertension kill silently, so does racism.

This article was written by Tamra Burns Loeb, adjunct associate professor-interim, University of California, Los Angeles; Alicia Morehead-Gee, adjunct assistant professor, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, and Derek Novacek, assistant project scientist, UCLA School of Medicine. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.