From skateparks to neglected historic sites and marine sanctuaries, UCLA professor Justin Dunnavant set himself on a venturous path at an early age.

Growing up in Frederick, Maryland, Dunnavant and his friends skated from youth into adulthood, adopting a do-it-yourself attitude in building skating ramps and documenting tricks. In some ways, those early adventures were not all that different from the dig in Belize where Dunnavant fell in love with his chosen field, archaeology.

Now, as assistant professor of anthropology at UCLA and an affiliate of the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, Dunnavant’s research projects and work with organizations like National Geographic are taking him all over the world, from diving for WWII wrecks in Hawaii to exploring the archaeology of slavery in the Caribbean. Back in Los Angeles, he teaches classes on Caribbean Archaeology, the African Diaspora, and a course on the Anthropology of Skateboarding — circling back to his initial love of skate culture.

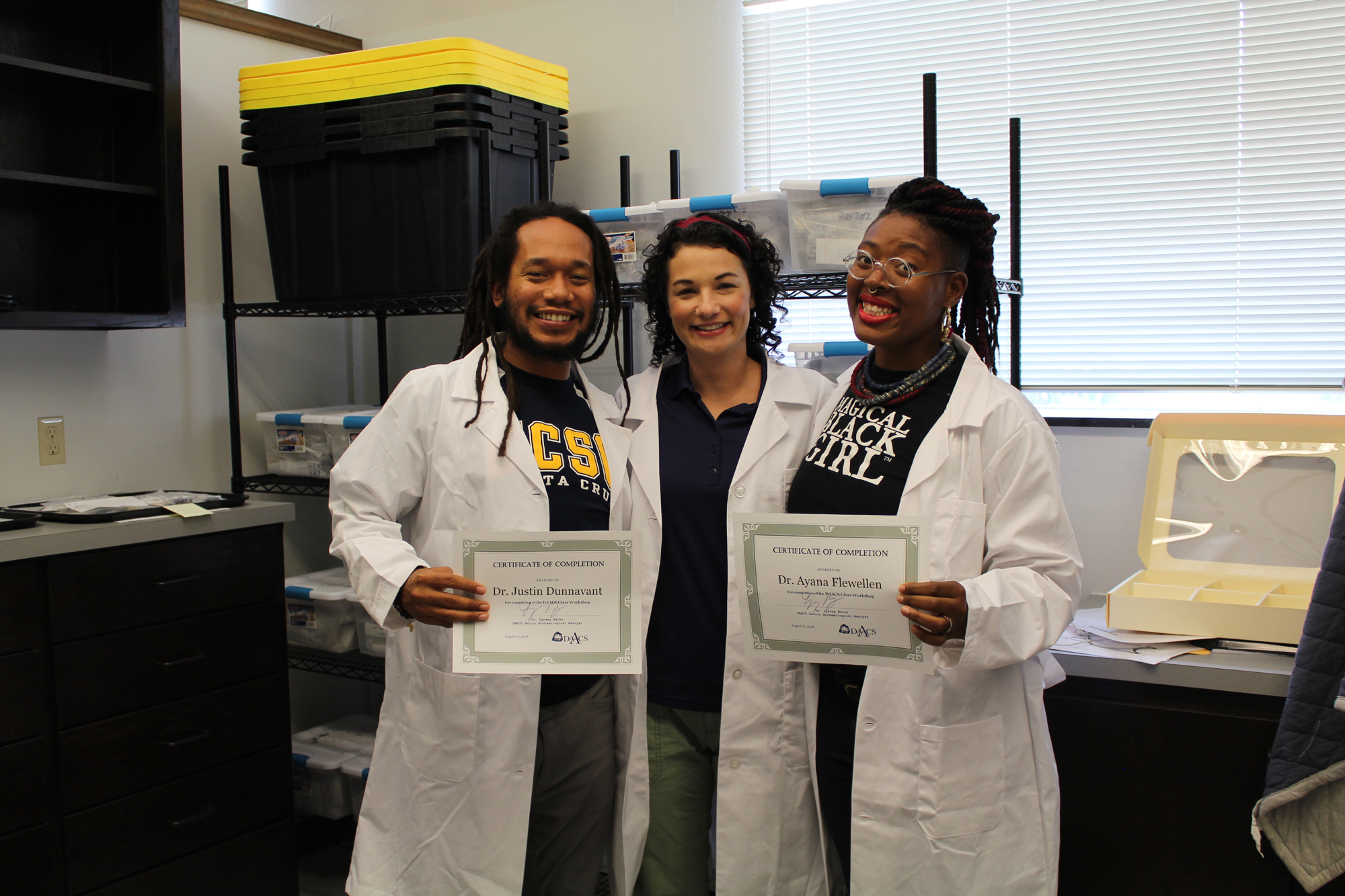

While getting your hands dirty is part of the field’s allure, deciphering the past and understanding our ancestors requires more than individual grit. Along with former UC Riverside professor Ayana Omilade Flewellen, Justin Dunnavant founded the Society of Black Archaeologists in 2011 to advance the study of the African diaspora. The group has now grown into an international force, providing mentorship and support for roughly 300 Black scholars around the world, while centering communities and perspectives historically marginalized in the field. Under the leadership of new president Alexandra Jones, a UC Berkeley Ph.D., the organization is poised to continue growing in influence and scope.

Archaeology in a wet suit

In mass media, archaeology is usually a pretty dusty affair. In Dunnavant’s case, replace the shovels with scuba gear. Dunnavant is an historical archeologist with a specialty in maritime archaeology. He explores the oceans — once our highways, he notes — to better understand the history of the African diaspora, from the African explorers who sailed the oceans well before Columbus to shipwrecked slave vessels.

Dunnavant’s interest in archaeology was piqued while studying abroad as a Howard undergraduate. Seeking a professional career that would allow him to travel, Dunnavant figured international business was the ticket — until his program handed him a shovel and asked him to start digging in the Belizean rainforest.

“I always had an interest in African diaspora and African history, and when I realized archaeology was pretty much the precursor to what we read in history books, I really fell in love with it,” he explains.

Dunnavant’s subfields, maritime and African diasporic archaeology, are relatively new additions to a discipline that dates back to prehistoric times (Ancient Mesopotamian kings, as it turns out, were curious about people even older than themselves). Archaeology has often been the realm of those in power, with the resources to be acquisitive. “Even 100 years ago, archaeology tended to be wealthy individuals who had money and would go out and excavate and maybe put objects in a museum,” Dunnavant says.

This is a legacy that organizations like the Society of Black Archaeologists seeks to disentangle by focusing on understanding material cultures from within the communities that produced them, rather than extracting cultural relics from them. A shifting ethos that centers community needs and a slowly diversifying field are helping to shift how objects are studied and who studies them, even as recent surveys find that only 1 percent of archaeologists are African American.

“Part of what I'm trying to do now is rethink archaeology into this idea of reclaiming ancestral memory,” Dunnavant says. “As humans, we have done so many things we have no collective recollection of, like building the pyramids. What we’re trying to do in archaeology is actively remember what it is that we have forgot.”

For Dunnavant, the work of reclaiming ancestral memory requires moving beyond the idea that we need to suppress personal identity or history in approaching the past. “The questions I ask from my experience are going to be different than the questions someone else asks from theirs,” says Dunnavant. “I think the field is much richer if we diversify and encourage people to fully explore who they are and then take those questions and see how the present has a direct relationship to what happened 3,000 years ago across the world. It allows us to write new stories of our regions and ourselves.”

This way of practicing archaeology is inspired by Indigenous archeologists who talk about an Archaeology of the Seventh Generation, which asks how we can not only pass on knowledge seven generations down the line, but how historic objects and practices can be studied in their full, culturally specific relevance.

A forthcoming article in Current Anthropology by Dunnavant and Flewellen builds on this idea by exploring the concept of the archeology of redress, which uses the information gleaned through archeological study to think about how to remedy past actions.

“With ecology and slavery, for instance, we’re saying we understand that during slavery, coral reefs were mined for coral, and it killed off fish populations and coral populations. So we’re actively getting involved in coral restoration work as a result of that. We want to encourage people in other areas to think creatively around what some type of redress looks like in other areas.”

From the Smithsonian to St. Croix

For SBA co-founder and Stanford assistant professor of anthropology Ayana Omilade Flewellen, the love of history came early. Growing up in Tacoma Park, Maryland with a single mother, Flewellen, who uses they/she pronouns, visited the National Mall with their mom, spending hours in the Natural History and American History museums. This early love guided her all the way into undergraduate work at the University of Florida, where a class taught by James Davidson, “Archaeology of African American Life and History,” provided an entry point for how history, identity and curiosity could meet.

“Not many colleges have an African American archaeology-centered course, so that was really important for me,” Flewellen says. “My introduction to this field centered my own lived experiences and the experiences of my ancestors. I felt more connected to it, whereas a lot of students of color might actually have the opposite experience of not feeling seen, or feeling like their ancestral heritage is not truly appreciated, or worse, extracted.”

Field work in nearby Kingsley plantation in Jacksonville, Florida, helped this calling really click.

“I learned about Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley, who was the Senegalese mistress to the white plantation owner, and I developed a whole undergraduate honors thesis around the lack of storytelling around Black women and their lived experiences at this particular heritage site. That became my master’s research.”

In Florida, Flewellen met Dunnavant, then a first-year master’s student, after she convinced professors to let her join higher-level classes usually off limits to undergrads. Field work took them both to Bukoba, Tanzania, where they solidified a working relationship. Before Flewellen left for the University of Texas to learn under Maria Franklin, the UC Berkeley–educated Black feminist archaeologist whose teaching had influenced Davidson’s course, the duo founded the Society of Black Archaeologists. Like many founding stories, this started off with a bold pitch.

“We just emailed everyone we knew and told them to opt out if they wanted to. No one did,” Dunnavant laughs.

The need to create the organization felt obvious. “We visited the Association of Black Psychologists at a conference and saw what they were able to do in their space in the field of psychology,” Dunnavant says. “And we said, if we could build out something similar in archaeology, we think that we could really begin to move the needle in terms of what sites are being excavated, how they’re being excavated and what we’re doing with historical material.”

SBA partners with the communities it studies alongside, relying on collaboration to not just fill but identify knowledge gaps. Stories that have been historically suppressed or set aside are centered. One of Flewellen’s many projects is to examine ornamentation and fabrics worn by enslaved women. Period photographs of women in the fields were staged, their clothing pre-selected. Flewellen wants to be closer to the truth.

“With the Society of Black Archaeologists, we want to change the face of archaeology, to ensure that folks of color, Black folks have their voices and their faces seen as people who are doing this work and unearthing their own history,” Flewellen says.

SBA’s impact goes beyond the history of African Americans or the African diaspora, Flewellen notes, reflecting the importance of diversity across the field of archeology.

“Since the establishment of SBA, we’re also seeing the kind of uptick and visibility of Chinese-American archaeologists, for instance, who are expressing a need for representation and visibility, especially with so many sites out West that focus on Chinese heritage and history in this country. There needs to be more people of Chinese ancestry and descent doing and leading this kind of work. It’s been exciting to see how SBA’s mission also has expanded outward to other nonwhite practitioners in this field.”

Centering community in SBA’s archeology work takes many forms. In an ongoing project in St. Croix, an island colonized first by the Danes, then by the United States, archaeologists including Dunnavant, Flewellen and UC Berkeley’s William White are trying to engender a sense of cultural stewardship for local youth about the site — the artifacts, after all, don’t belong to some abstract history, they belong to them. Appreciating the value they held for ancestors, the intimacy, can help us “get quiet and get close,” as Flewellen puts it, and regard found items not as commodities in a story of the commodification of people, but as a way to connect, revere and hold tenderly the people of the past.

Ayana Omilade Flewellen

Putting names to the past

For Alexandra Jones, getting close to the people of the past has been a throughline of her work since she started her doctorate at UC Berkeley. While she was mulling over her doctoral work, a church in Maryland, founded in the antebellum era, approached her. The church was built on land sold by an enslaver to a freed family; the family in turn founded a spiritual community for themselves and nine other families still enslaved on the plantation. Jones had been working on the study of diasporic religions in Cuba but had come to appreciate the need for archaeology within her own community. The church’s request dovetailed perfectly with Jones’ desire to bring the power of archeology to revealing the stories of home.

Working with the community to develop oral histories and ethnography from the descendants of the original founders of the church, Jones was able to reconstruct the land’s lost history. The local records office counted only seven people laid to rest in the church cemetery. But in the course of her work, Jones collected the names and dates of 27 people buried there. A community project cleared more of the old graveyard, allowing Jones and her collaborators to find the headstones of more than 70 people. Today, the number of people found in the graveyard is now approaching 200.

This work hasn’t just helped shed light on the past — it’s helped preserve it for the future. In 2020, the state of Maryland developed plans to expand a highway into the historic graveyard. The church approached Jones again. Years after her dissertation, she is now on the Board of Directors of the cemetery.

“I never thought that I would be a caretaker of a cemetery,” Jones says, smiling. “But we conduct archaeology education programs, give educational talks, and are in the process of creating a short film to elevate the story of this historic site.”

“The descendant community wants to make sure this independent black community that was already struggling in real life doesn’t endure that kind of injustice in death as well. If it hadn’t been for their story, I wouldn’t be here today. I felt it was my duty to come back and help this community with my time.”

Inspired by her experience with the church and its community, Jones now runs a D.C. nonprofit called Archaeology in the Community, which turns 15 this year. It celebrates local archeology and creates educational programming for children who may not otherwise be exposed to the field. The initial funding for the project and the inspiration came from her time at UC Berkeley, where visiting local classrooms and introducing students to archaeology was a requirement. Hearing a teacher say “see you next semester” following one of her visits made Jones wonder why she had never heard from archaeologists in her community growing up — and determined to change that.

Like other members of SBA, Jones is keenly aware of the impact archaeology makes in day-to-day life, and how her work can influence others outside of academia.

“Archaeology shines a light on people in a way that the traditional history we were taught in school and trained to do, does not. What people forget is that when you do that, you elevate people.”

As a longtime board member and now president of SBA, Jones is equally passionate about driving that approach in the organization, along with providing the kind of mentorship you simply can’t make it in archaeology without.

“At SBA, we bring together scholars from different regions and continents so that we’re able to have these dialogues and talk about how we’re proceeding so that we aren’t making the same mistakes as our predecessors. We want to make sure we are working in collaboration with our Indigenous colleagues and with the organic knowledge of members of communities we work within.

“The only way that we change the field is by mentoring and guiding the next generation of archaeologists.”

From Dunnavant and Flewellen’s bold email in 2011, a vibrant group of international scholars has emerged, including some of the biggest names in the field. At their first in-person meeting a decade ago, featuring about eight early members, Theresa A. Singleton and Warren Perry, the second and third African Americans to get Ph.D.s in archaeology, showed up. They had been wanting to form this sort of professional organization for years — they just didn’t have the numbers. That’s not a problem anymore. And more young scholars are on the way.

“The mother of a student I taught just emailed me and said they're going to college to study anthropology and archaeology and I was like, ‘Holy mackerel! I made a difference,’” Jones says. For her, the dream project isn’t a dig — it’s that influence.

“I want to leave behind an institution that’s mission is to educate and highlight all of our importance in our shared history, culture and heritage.”

Learn more

Footage for video banner courtesy Ayana Omilade Flewellen.

Alexandra Jones