For too many people of color, traumatic encounters with the health care system are a reason to avoid going to the doctor. But for Aminta Kouyate, a UC medical student, it sealed her decision to become one.

Kouyate was an undergrad at UC Berkeley, tackling general chemistry and physics, when she woke up at 5 a.m. with debilitating abdominal pain. Doctors first suspected appendicitis — but when the imaging showed her appendix was fine, “the tone in the room changed immediately,” Kouyate said. She was left for five hours by an open exit door in a hallway in just a thin patient gown.

“I was told I could leave at any time because they were not going to give me what I was looking for,” she said. “They thought I was there to seek pain medication, that I did not actually have a medical emergency.”

Finally, a Black nurse noticed her sitting in the hall and made sure the doctors addressed her problem and gave her the care she needed. But the experience left its mark.

“Nobody should ever have to have to feel this way,” she said. “I thought to myself, ‘If I have anything to do with it, nobody’s ever going to treat another patient like this again.’”

Now a third-year student in the UCSF-UC Berkeley joint medical program, Kouyate is looking to make good on her promise. She is one of 365 students in the UC Programs in Medical Education, or UC PRIME, which works to address health equity issues in California. The program trains and places culturally competent physicians in medically underserved communities across California, from impoverished urban neighborhoods to rural areas with few doctors.

It is also one of the state’s most effective programs for producing a new generation of medical practitioners as diverse as California itself.

Kouyate has set her sights on becoming an emergency room physician in the same Oakland community she grew up in, where she was once left shivering in a hospital gown.

But she’s not stopping there.

Kouyate recruited some 250 students to join her as a COVID-19 vaccinator. She ran a workforce development for the San Francisco public health department to increase the number of underrepresented students in HIV/AIDS research and worked with Dr. Aisha Mays, a physician at Oakland’s Dream Youth Clinic, to help residents of a local youth shelter build the “community garden of their dreams.”

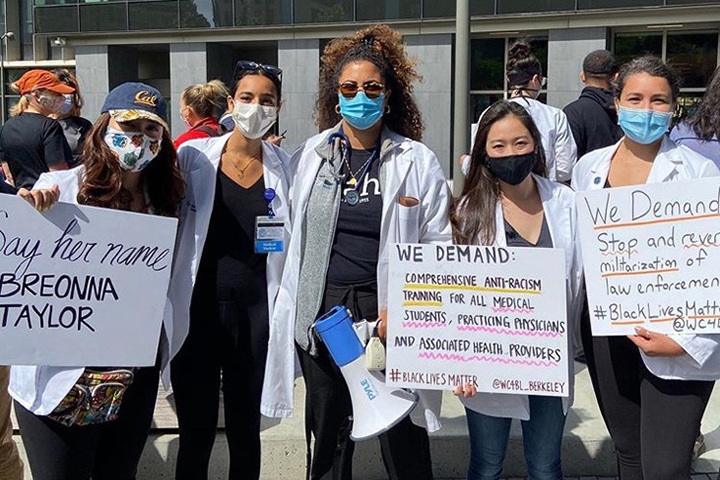

She also co-founded the UC Berkeley chapter of White Coats for Black Lives. The organization, launched by UC medical students, mobilizes the health care community against racism and the practices that harm Black people and their communities.

As if that’s not enough, she’s written her thesis on developing an anti-racist curriculum for HIV health care providers. It is focused, in part, on considering the impacts of racism as a negative determinant of health.

“There’s this idea that people of color don’t trust the health care systems because of historic insults,” Kouyate said. “But it’s also these everyday insults they’ve experienced or their cousin or their mama experienced. One of those bad interactions, and the person doesn’t come back for 10 years, and they don’t get screenings and then they get [a preventable illness] because it wasn’t caught early enough.”

Doctors who ‘get’ the communities they serve

Years of research confirms that people get better care and have more trust in doctors who share their cultural backgrounds. Yet there remains a dearth of Black, Latino and Native American physicians.

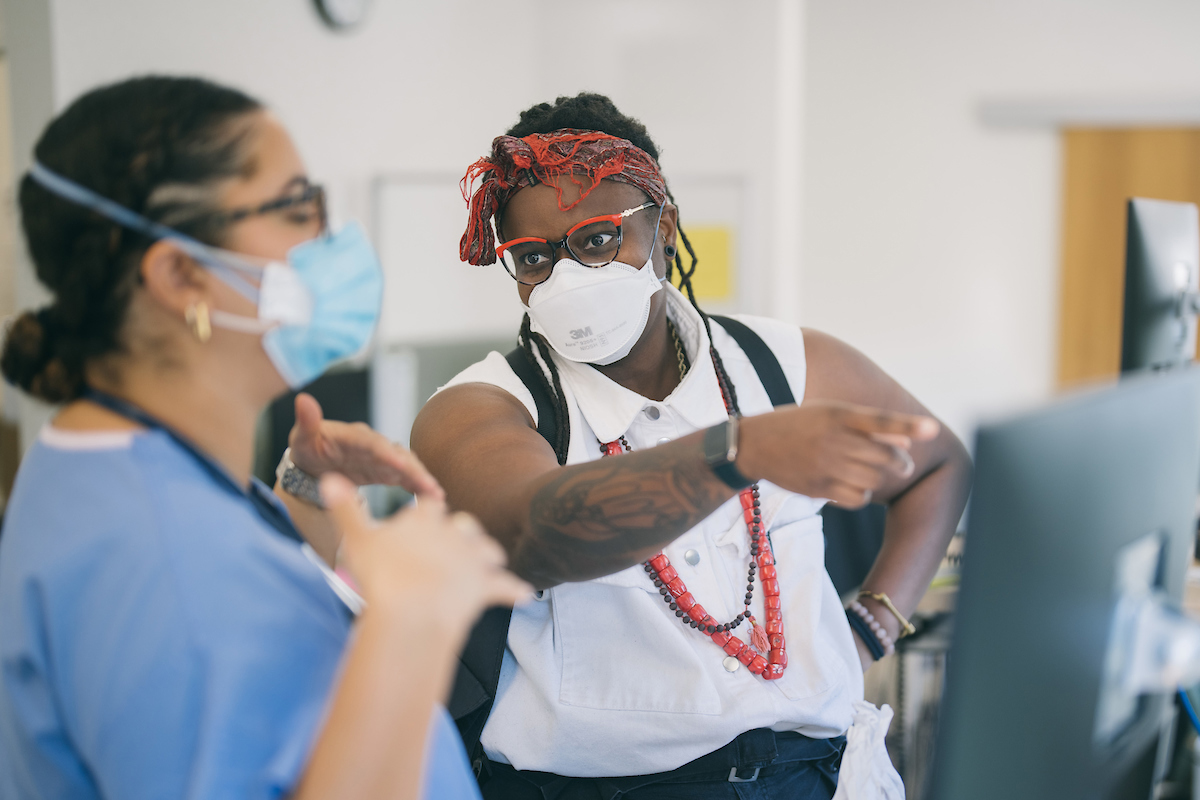

That disparity itself contributes to unequal health outcomes, said Dr. Maisha Davis, a UCSF graduate and PRIME alum who supervises Kouyate’s clinical practice at the Maxine Hall family medical clinic in San Francisco.

When patients have a physician they can relate to — especially one they know from the community — they are more likely to share their real health concerns, get a vaccine or get that follow-up appointment.

“If people can’t bring their whole selves to the doctor, they’re not going to get the best care,” Davis said. “But the medical profession doesn’t necessarily feel like a safe and welcoming place to people who don’t fit the mold.”

According to a recent UCLA study, the share of Black physicians as a portion of the population has barely changed in the last 120 years.

The reasons for this appalling fact are many and varied, including systemic inequalities in education; a lack of mentors and advisers; barriers to applying to medical school; and a curriculum and culture that make medical school less welcoming to students from underrepresented groups.

The UC PRIME program, which was launched in 2004 and has now expanded throughout the state, has had notable success in diversifying the physician pipeline. Almost 70 percent of participants come from groups traditionally underrepresented in medicine. That compares to 14 percent enrolled in medical schools across the nation.

The program is preparing to expand even further, with $13 million in additional funding from the state that will allow it to enroll nearly 500 students by 2026.

Part of its success: creating networks of mentors, peers and practicing physicians that make medicine a more welcoming place for doctors from underrepresented groups.

Black doctors carry a disproportionate burden when it comes to mentoring and managing caseloads of patients who want to see the one doctor they trust, Davis said.

On a recent day at the Maxine Hall clinic, Davis mentored Kouyate as her attending physician, saw a full roster of patients and even squeezed in two more drop-in patients who had been unable to get regular appointments. When the day was over, Davis spent extra hours wrangling with a drug approval agency to get a patient needed medication.

Davis relies on fellow PRIME alumni for moral support and also refers many patients to them. “It’s not enough getting black and brown folks into the machine. It’s that community that forms — folks who can be constant reminders of why we keep doing this work,” Davis said.

Along with training a new, more diverse generation of doctors, UC PRIME produces champions for the communities they serve. Of the 470 doctors who have graduated, many have gone on to work in medically underserved areas both as physicians and as advocates.

“Just because you come from the community, you don’t immediately know how to serve it,” Kouyate said. “We know what the issues are, but we also need more training on how to navigate and create effective solutions and really be leaders in the field. I think PRIME is really trying to train us to do that, and that’s been its mission from Day One.”

A doctor’s journey

Although she isn’t yet a licensed physician, Kouyate has already seen her interactions affect the lives of patients. There are people she’s helped convince to get vaccinated against COVID by sharing her own personal story as someone who’s had allergic reactions to vaccines. There are people she has connected with through her work in HIV whom she’s convinced to seek out treatment and preventive care.

She has sat with people who are getting a life-changing diagnosis and others who are so terrified of doctors that they are reluctant to go through with routine procedures. She’ll ask about their kids’ birthdays or the best places to eat in the neighborhood to calm them down and put them at ease.

“Aminta is grounded and authentic, and people can feel that,” Davis said. “It does so much work in dismantling mistrust,” Davis said. “It can be a foot in the door that had been slammed shut.”

Kouyate’s understanding of health disparities was shaped by the East Bay community where she grew up. Oakland’s Mosswood Park was a vibrant neighborhood, humming with festivals in the park, pick-up basketball games, folks having barbecues and cookouts.

With three hospitals in walking distance and medical offices on almost every corner, the area would hardly seem to qualify as medically underserved. But the health care services that dominated the area were largely out of reach to its many uninsured residents, members of Kouyate’s family included. “Seeing that disparity is a big part of why I want to become a physician, to actually serve that community.”

At the time, however, medical school was not remotely on her radar. As a teenager, she wasn’t at all academic. “I think I had a 1.0 grade point average in high school at one point,” she said. Teachers who recognized her potential pushed her to pursue community college. Once there, she quickly found her groove and was able to transfer to UC Berkeley in two years.

“I think I will be a better physician for being part of the California Community College system,” she said. “It gives you such a phenomenal perspective on real people’s struggles. It’s all kinds of ages, backgrounds –—very much the community I’ll serve as patients.”

Kouyate ultimately became an outstanding student, testing in the top 10 percent of the MCAT and acing the chemistry and physics sections she’d especially struggled with as an underclassman.

But making it to UC Berkeley and then to medical school wasn’t easy. PRIME let Kouyate build a support network that has been critical to sticking it out.

Along with Davis, many of the other physicians she has trained with are PRIME alumni, such as her thesis director, Dr. Monica Hahn. She’s also had the support of peers like roommate Camila Hurtado and friends who gather to practice suturing techniques over El Farolito burritos.

Now she’s paying it forward: As part of White Coats for Black Lives, she helped secure a $65,000 grant to set up a national seminar program to demystify the process of applying to med school.

“There is so much information out there, but when you’re going through it, it feels so isolating,” Kouyate said. “You feel like everybody knows something you don’t.”

Making a difference with every patient

Today, Kouyate’s schedule is a whirlwind of surgical rotations, family clinic visits, lectures and small group classes. Whenever there’s a minute of downtime, it’s for studying and practicing sutures.

There’s a lot to learn and take in. But just by connecting with people on an individual level, she has already seen how she is able to promote better health outcomes.

One patient especially stands out as an example of what makes it all worth it: an elderly woman Kouyate saw at Highland Hospital in her first year of med school, just as she was preparing to start her clinical training.

“At first, when I came in, she didn’t want to answer any of my questions. So we just sat and chatted about life for the next 40 minutes.”

Before long, the patient was sharing details with important bearing on her health, as well as medical concerns her doctors had no idea about. Working with Kouyate, the physician was able to draw up a much more detailed plan for her care.

“At the end of the visit, [the patient] asked me how soon I was graduating. And then she said, ‘Well, I better hang in there, because I’m coming.’”

That was over two years ago, but Kouyate is still planning on holding the seat.