Robert Monroe, UC San Diego

Carbon dioxide is accumulating in the atmosphere faster than ever — accelerating on a steep rise to levels far above any experienced during human existence, scientists from NOAA and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego announced today.

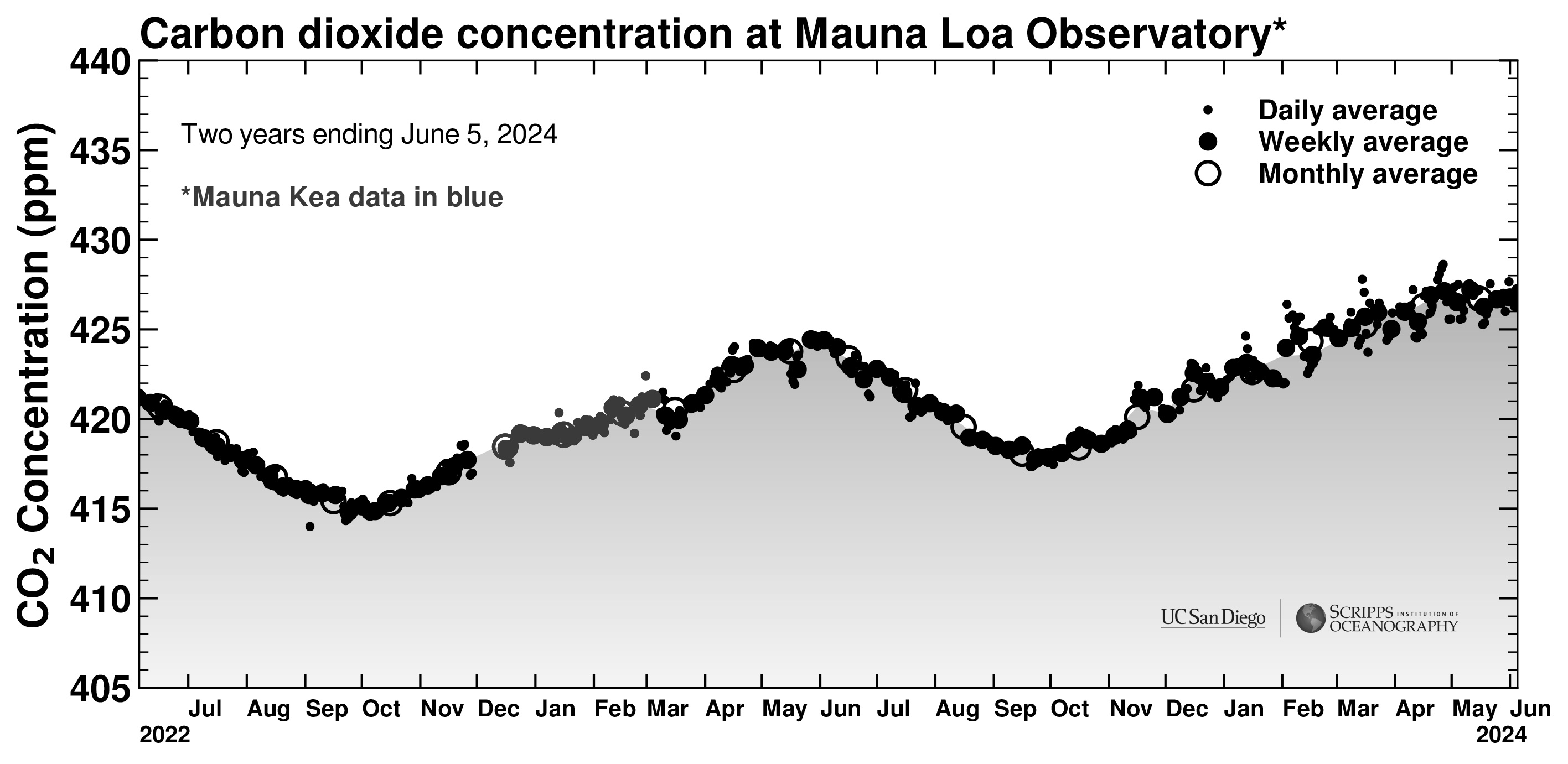

Scientists at Scripps Oceanography, which initiated the CO2 monitoring program known as the Keeling Curve at Mauna Loa in 1958 and maintains an independent record, calculated a May monthly average of 426.7 ppm for 2024, an increase of 2.92 ppm over May 2023’s measurement of 423.78 ppm. May is historically the month when CO2 reaches its highest level in the Northern Hemisphere.

When combined with 2023’s increase of 3.0 ppm, 2022 to 2024 has seen the largest two-year jump in the May peak of the Keeling Curve in the NOAA record. For Scripps, the two-year jump tied a previous record set in 2020. From January through April, NOAA and Scripps scientists said CO2 concentrations increased more rapidly than they have in the first four months of any other year. The surge has come even as one highly regarded international report has found that fossil fuel emissions, the main driver of climate change, have plateaued in recent years.

“Not only is CO2 now at the highest level in millions of years, it is also rising faster than ever. Each year achieves a higher maximum due to fossil-fuel burning, which releases pollution in the form of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere,” said Ralph Keeling, director of the Scripps CO2 program that manages the institution’s 56-year-old measurement series. “Fossil fuel pollution just keeps building up, much like trash in a landfill.”

Keeling also noted that other measurements recorded in recent months yielded another troubling superlative when the March 2024 reading achieved the highest 12-month increase for both Scripps and NOAA in Keeling Curve history.

Like other greenhouse gases, CO2 acts like a blanket, preventing heat from radiating from the atmosphere into space. The warming atmosphere fuels extreme weather events, such as heat waves, drought and wildfires, as well as heavier precipitation and flooding.

“Over the past year, we’ve experienced the hottest year on record, the hottest ocean temperatures on record and a seemingly endless string of heat waves, droughts, floods, wildfires and storms,” said NOAA Administrator Rick Spinrad. “Now we are finding that atmospheric CO2 levels are increasing faster than ever. We must recognize that these are clear signals of the damage carbon dioxide pollution is doing to the climate system, and take rapid action to reduce fossil fuel use as quickly as we can.

Levels measured at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory by NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory surged to a seasonal peak of just under 427 parts per million (426.90 ppm) in May. That’s an increase of 2.9 ppm over May 2023, and the fifth-largest annual growth in NOAA’s 50-year record.

The record two-year growth rate observed from 2022 to 2024 is likely a result of sustained high fossil fuel emissions combined with El Niño conditions limiting the ability of global land ecosystems to absorb atmospheric CO2, said John Miller, a carbon cycle scientist with the Global Monitoring Laboratory. The absorption of CO2 is changing the chemistry of the ocean, leading to ocean acidification and lower levels of dissolved oxygen, which interferes with the growth of some marine organisms.

For most of the past half century, continuous daily sampling by both NOAA and Scripps at Mauna Loa provided an ideal baseline for establishing long-term trends. In 2023, some of the measurements were obtained from a temporary sampling site atop the nearby Mauna Kea volcano, which was established after lava flows cut off access to the Mauna Loa Observatory in November 2022. With the access road still buried under lava, staff have been accessing the site once a week by helicopter to maintain the NOAA and Scripps in-situ CO2 analyzers that provide continuous CO2 measurements.

Scripps geoscientist Charles David Keeling initiated on-site measurements of CO2 at NOAA’s Mauna Loa weather station in 1958. Keeling was the first to recognize that CO2 levels in the Northern Hemisphere fell during the growing season, and rose as plants died in the fall. He documented these CO2 fluctuations in a record that came to be known as the Keeling Curve. He was also the first to recognize that, in addition to the seasonal fluctuation, CO2 levels rose every year.

NOAA climate scientist Pieter Tans spearheaded the effort to begin NOAA’s own measurements in 1974, and the two research institutions have made complementary, independent observations ever since.

While the Mauna Loa Observatory is considered the benchmark climate monitoring station for the northern hemisphere, it does not capture the changes of CO2 across the globe. NOAA’s globally distributed sampling network provides this broader picture, which is very consistent with the Mauna Loa results. Similarly, the Scripps CO2 program operates 14 global sampling stations.

The Mauna Loa data, together with measurements from sampling stations around the world, are incorporated into the Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network, a foundational research dataset for international climate scientists and a benchmark for policymakers attempting to address the causes and impacts of climate change.

Measurements by the Scripps CO2 program are supported by the US National Science Foundation, by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation, and by Earth Networks, a technology company that is collaborating with Scripps to expand the global GHG monitoring network.

In-kind support for field operations is also provided by NOAA, the National Science Foundation, Environment Canada, and the New Zealand National Institute for Water and Atmospheric Research.

-- Adapted from NOAA

Learn more about research and education at UC San Diego in: Climate Change

March 2024 saw the largest year-over-year increase in monthly average CO2 concentration in Keeling Curve history.