Sean Nealon, UC Riverside

John Chater remembers the day vividly. He was about 2 years old. His grandfather gave him a dark, purplish pomegranate. Happily, he opened it and starting eating.

He quickly realized his mistake. He was wearing his new light brown suede shoes. The pomegranate juice quickly found the shoes, leaving a permanent scar.

“That was my first experience, that I remember, with pomegranates, and it involved getting in trouble,” Chater said. “Because it was so delicious, I didn’t realize it would stain.”

More than 30 years later, Chater is a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Riverside, with a focus on pomegranate research and a 2016-17 UC Global Food Initiative student fellow. He is building on the work of his grandfather, S. John Chater, who was a maintenance worker at hospital but developed a cult following among rare fruit growers in California for developing new varieties of pomegranates.

The younger Chater, working with varieties selected from the National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Winters, including several developed by his grandfather (who died in 2002), is working to better understand the commercial potential of these varieties.

Currently, 90 to 95 percent of pomegranates are one variety: Wonderful, Chater said. (In addition, California grows more than 95 percent of pomegranates in the United States, he said.)

Working under Don Merhaut, UC Cooperative Extension specialist for ornamental and floriculture crops at UC Riverside, Chater has set up pomegranate variety trials in Riverside and Camarillo.

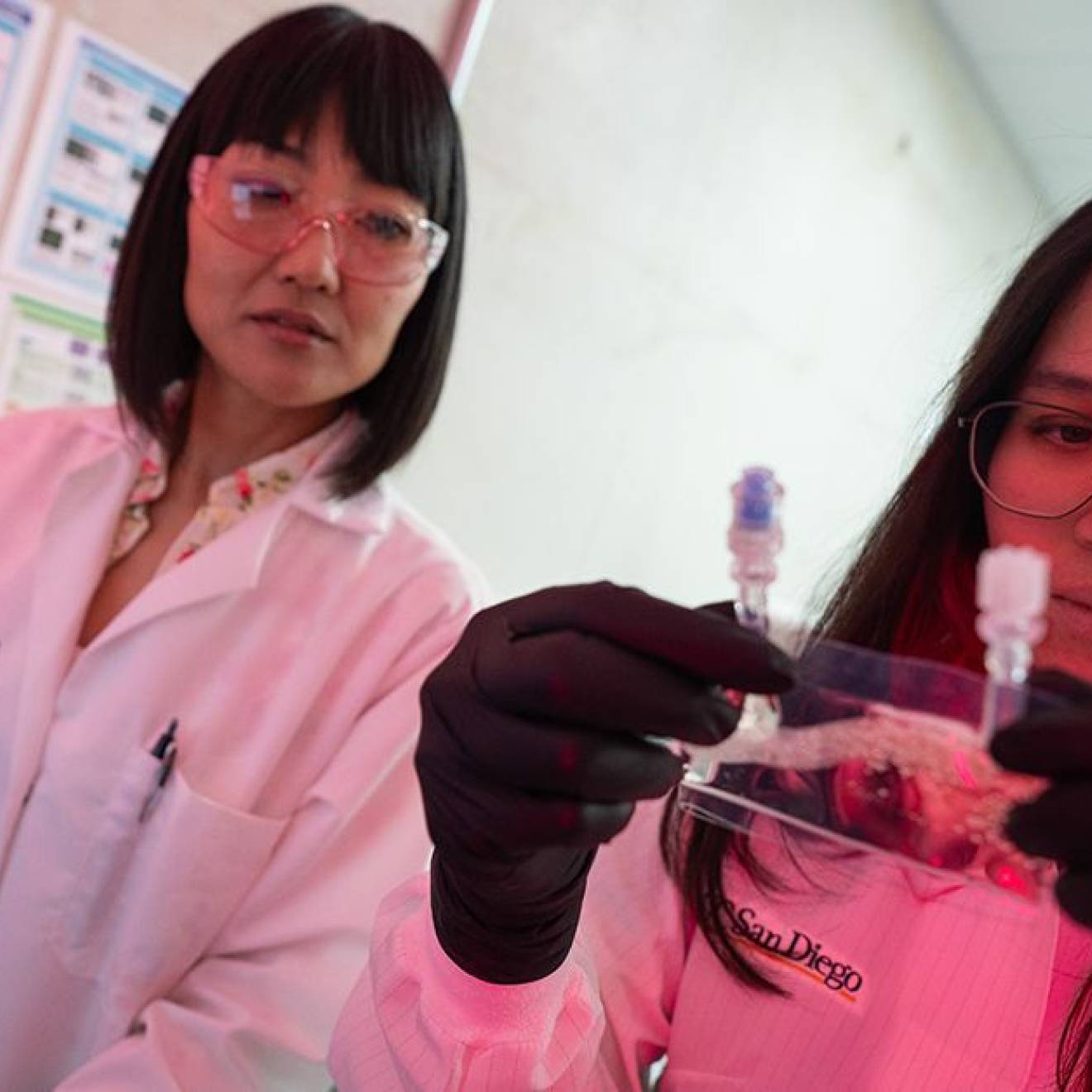

Credit: UC Riverside

They have planted 12 pomegranate varieties, 15 trees per variety, to evaluate their establishment, precocity (flowering and fruiting), usefulness to growers and desirability to consumers.

Of the 12 varieties, 10 are edible (Parfianka, Desertnyi, Wonderful, Ambrosia, Eversweet, Haku Botan, Green Globe, Golden Globe, Phoenicia and Lofani) and two are ornamental (Ki Zakuro and Nochi Shibori). The ornamental varieties, whose flowers look like carnations, could be of interest to the floriculture industry, Chater said.

The researchers want consumers to be able to go to supermarket, and, like apples and citrus, be able to buy different varieties of pomegranates that vary in sweetness, seed hardness and color. (The varieties Chater is studying range in color from green to yellow to pink to orange to red to nearly purple.)

Chater set up the trials in Riverside and Camarillo to evaluate the difference between the cooler coastal climate and the warmer inland climate.

The prevailing thought is that more acidic varieties do better in inland conditions because the high summer temperatures reduce the acidity before the fruit is picked in the fall.

For example, a variety such as Wonderful, which is high in acidity, is grown commercially in the Central Valley. But, Eversweet, which has a lower acidity, does well on the coast.

Related to color, some researchers believe that pomegranates color up because of cool night time temperatures. Therefore, trees planted on the coast tend to color up faster.

All that said, it is believed no one has done a comprehensive study, such as the experimentally-designed one Chater has set up, in the United States. It will allow him to study the interplay of variables including size, color, sweetness, acidity, antioxidant activities and seed hardness in different climate conditions.

Credit: UC Riverside