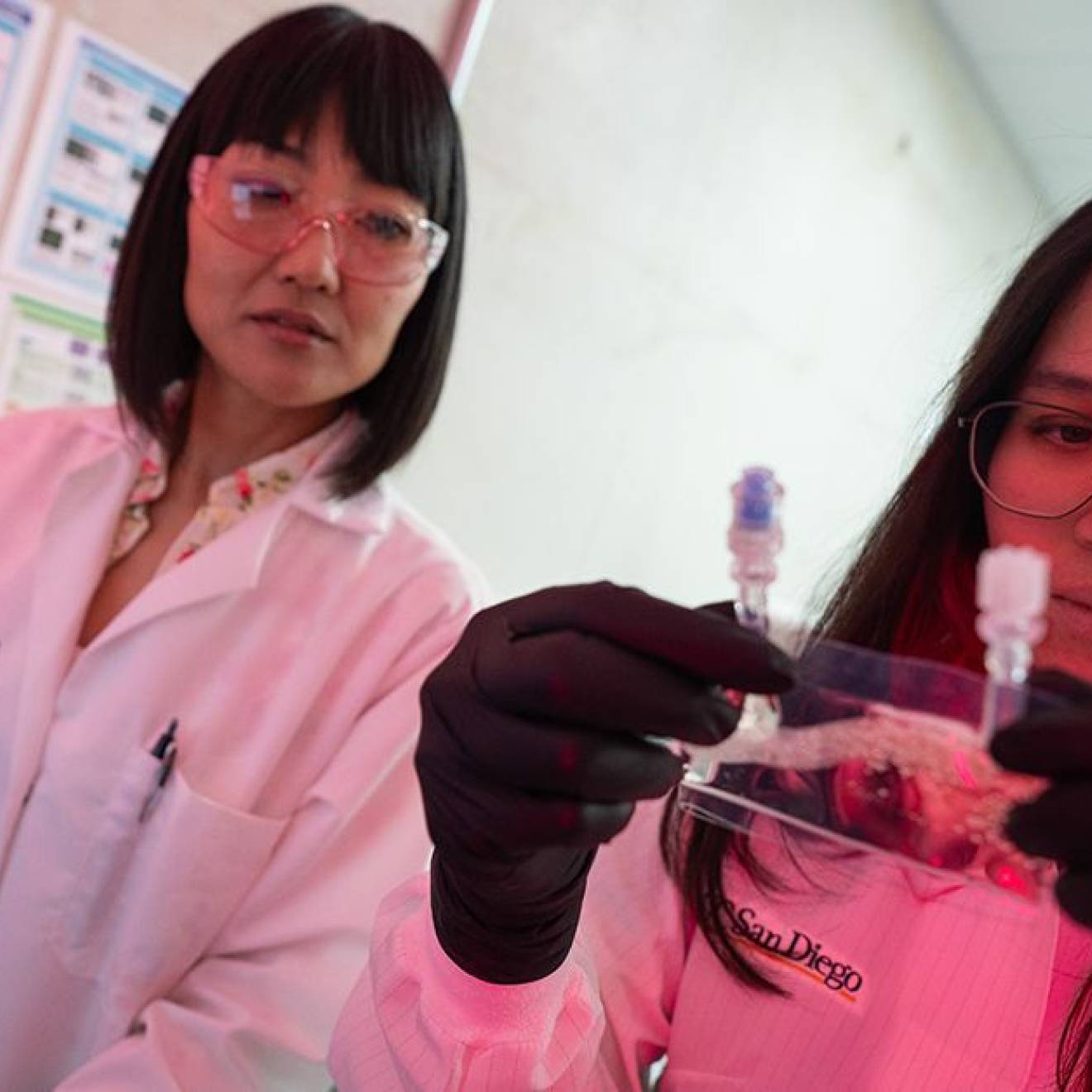

Kathy Wyer, UCLA

If you’re a parent or caregiver who is concerned that your child may have Autism Spectrum Disorder, getting a diagnosis as soon as possible is important because early intervention can be the key to the most optimal outcomes.

“As many studies have now shown, early intervention is critical for the best outcomes in children with autism, and many believe the earlier the better,” says Connie Kasari, a professor of Human Development and Psychology in the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies and the Department of Psychiatry at UCLA. “Only with a diagnosis can parents begin to obtain necessary intervention services for their child.”

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a growing public health concern that is often widely misunderstood, has been gaining attention ever since the U.S. Centers for Disease Control announced in 2014 that instances of autism are being diagnosed with greater frequency. According to the CDC, 1 in 68 children today have some form of the disorder; that’s an increase from 1 in 88 in 2012, and 1 in 110 in 2010.

A neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by delays and differences in social and communication behaviors, autism is a spectrum disorder — no two cases are alike, and its symptoms and severity vary from individual to individual. By all outside appearances, someone with ASD may not look any different from anyone else, but their condition may present them with significant emotional and behavioral challenges. Symptoms may last a lifetime, but there are interventions that help.

A founding member of UCLA’s Center for Autism Research and Treatment, an initiative that offers assessment and treatment services for the public as well as resources related to ASD, Kasari has developed targeted interventions that focus on improving early social communication development for at-risk infants, toddlers and preschoolers.

Her research involves populations that have traditionally been under-studied, such as children in under-resourced communities, minimally verbal children and girls.

Aiming to dispel some of the mystery that surrounds ASD by helping parents and others to understand its early indicators, Kasari has identified five questions to consider for recognizing ASD:

- Does the baby respond to his or her name when called by the caregiver? Typically developing infants will respond to their own name by turning their attention toward the person who called out to them. Yet babies who are later diagnosed with autism often don’t react to hearing their name called; only about 20% of the time do babies later diagnosed with autism turn and look at the person who called to them. Babies with autism often selectively respond to sounds; for example, a baby with autism might not acknowledge a parent calling their name, but they may react suddenly to a television being turned on. Parents often mistakenly suspect their child has a hearing problem.

- Does the young child engage in “joint attention”? Joint attention refers to an action when a child joins with another person to look at the same object or watch the same activity. Typical babies will shift their gaze from people to objects; look in the direction of where a hand is pointing; or show toys or other objects to others. For example, a baby might point to a puppy and look to his or her parent as if to say, “Look at that!” However, a child with autism will not often look in the direction pointed to by someone, not look back and forth from objects to people, nor show or point out an object or toy to a parent.

- Does the child imitate others? Typical babies will mimic others, whether through facial movements (making a funny face, for example), making a particular sound with their voice, or waving, clapping or making other similar gestures. Babies with autism, however, will much less frequently mirror another’s facial movements or hand gestures, and they will imitate less often using objects.

- Does the child respond emotionally to others? Babies are responsive to others; they smile when someone smiles at them, and initiate smiles or laughs when playing with toys or others. And when a typical child sees another child cry, they may cry themselves or act concerned. Yet a child with autism may not respond to someone’s smile or an invitation to play, and they may seem unaware of the distress or concerns of others. A child with autism can be emotionally unresponsive to others.

- Does the baby engage in pretend play? Young children love to “pretend play” — to act like they are a mom or dad, a baby, a horse or dog, etc. This ability to “pretend play” typically develops at the end of the second year. For example, a child may pretend to be a mom to a doll and wipe imaginary tears away, brush its hair or cook dinner for its doll on a toy stove. In contrast, a child with autism may not connect with objects at all, or in playing with certain toys, will focus exclusively on one toy over others, or may obsessively pay more attention to the movement of their own hands. Generally, an ability to pretend play is absent in children with autism under 2 years of age.

“It is important to note that in each of the five areas that we have flagged we are most concerned with behaviors that are absent or occur at very low rates,” says Kasari. “The absence of certain behaviors may be more difficult to pinpoint than the presence of atypical behaviors. But concerns in any of the five areas above should prompt a parent to investigate screening their child for autism. Several screening measures are now available, and information from the screener will help to determine if the parent should pursue further evaluation.”

This story is posted in Ampersand, the online magazine of the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies.