Wallace Ravven, UC Newsroom

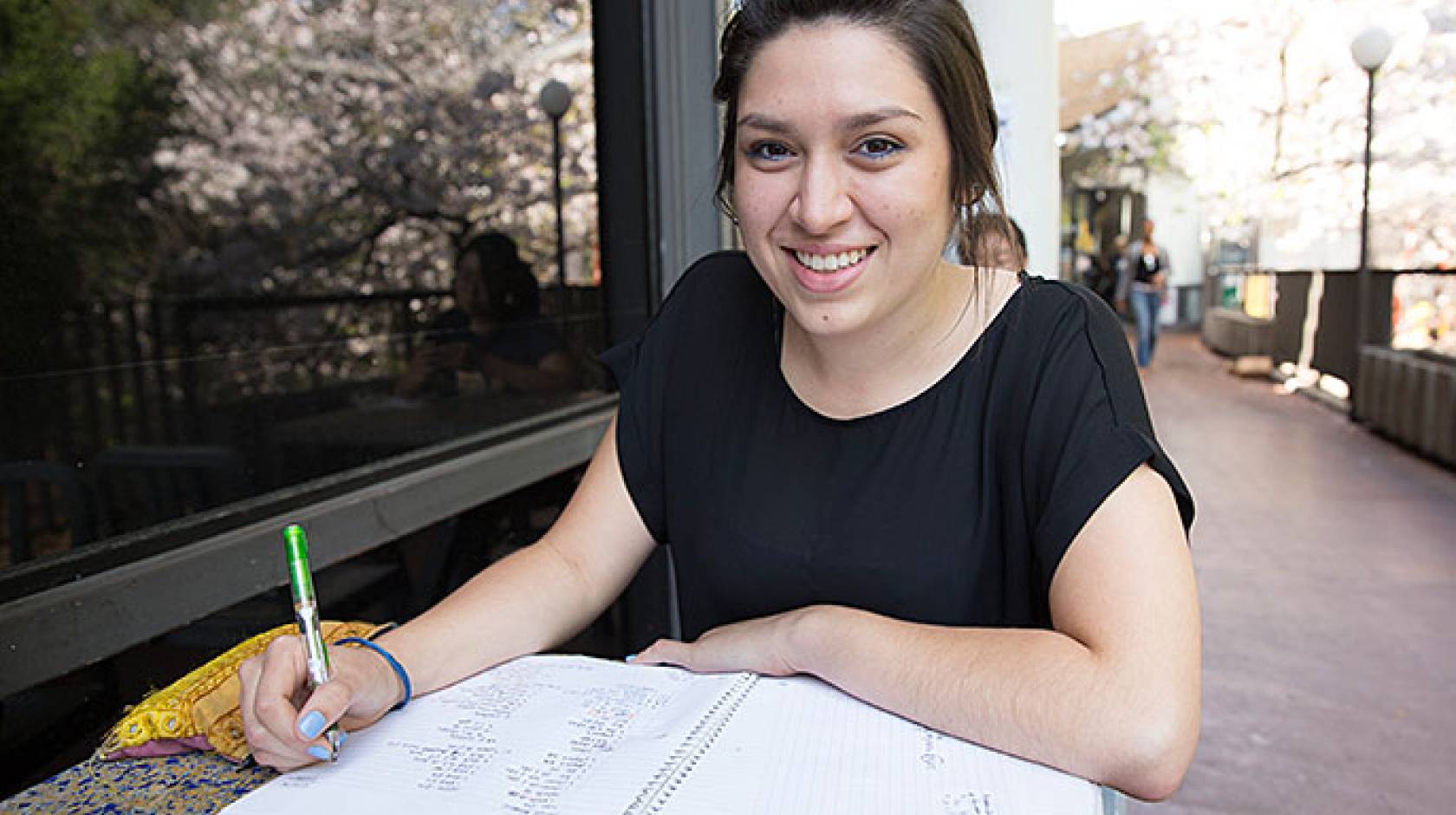

For Maritza Cardenas, life as a Berkeley freshman is exciting, and more than a little daunting. She is majoring in molecular and cellular biology, and plans to go to medical school. But there’s a minor hurdle: Freshman chemistry is the first laboratory class she’s ever had.

Growing up in the central California agricultural town of Salinas, Maritza didn’t get as much science prep as most of her fellow Cal classmates.

“I wasn’t very exposed to the idea of science in high school, but as I was applying to college and seeing how competitive it was, there was always this word ‘research.’ I think one of my main drives was being part of research — even though I really didn’t have a clear sense of what it meant.”

She got her chance to learn what it meant the summer after high school as one of 16 Salinas teens participating in a two-year program that trained them in public health and biomedical research while at the same time focusing on a potential health hazard to young women in the community.

The project, funded by UC’s California Breast Cancer Research Program, taught the students to design and carry out public health research and how to best reach out to their community to gather data and inform people about health risks. The teens also collected and prepared material for laboratory analysis.

The training focuses on potential dangers posed by chemicals known as endocrine disrupters, found in shampoos, face creams and other personal care products. Endocrine disrupters interfere with normal hormonal function, and are thought to pose a particular threat during the teen years when hormone-driven development accelerates.

The project, called HERMOSA (Health & Environmental Research on Makeup Of Salinas Adolescents), is a collaboration between Berkeley’s School of Public Health and Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas, a network of clinics providing primary health care to low-income and agricultural communities in Monterey County.

The team effort drew on a Salinas-based youth council developed by the Public Health School’s Center for Environmental Research and Children's Health, or CERCH, where teens gain leadership experience and focus on environmental health issues of particular concern to the community. Public Health School professor Kim Harley is a co-director of HERMOSA.

Kimberly Parra, the project’s other co-director and herself a Berkeley grad, praises Maritza’s discipline and persistence, but singles out one trait that she thinks has mattered most:

“The No.1 quality — the reason Maritza has been able to flourish — is that she really cares about her community and she’s very confident that she can influence it. She’s very humble at the same time.”

Growing up in Salinas, Maritza says her family was on Medi-Cal.

“We were receiving a lot of assistance. Being in that position, and seeing that it’s a big part of Salinas, I’m hoping to return home after medical school and start a clinic there.

“I see myself as the kind of doctor who has relationships with patients. I feel like I could be the kind of health provider that can educate patients, focusing on prevention, helping them help themselves.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Maritza has followed up her HERMOSA experience with a part-time job at CERCH — that’s in the afternoon, following a typical morning: an 8 a.m. Cal circuit training class, chemistry and calculus.

Dressed in her gym garb, she looks like the young student she is: blue headband across her dark hair, black stretch pants and a light sweatshirt, and nails painted blue. But she knows what she’s about, and she has a focus way beyond her freshman year.

“The most important thing I learned from HERMOSA was all the steps it takes to carry out research, even before the study begins. Even knowing how to interact with the participants you interview — that’s a whole other thing you have to learn.

“Now working for CERCH,” she says, “a big drive for me — and I think the center as well — is closing the gap between science and the public. So, I really see myself going in that direction because I believe that this education shouldn’t be this lofty thing that only some people are part of.

“I think it should be expanded to other people. It’s hard because sometimes there is not that much access. But if we can break it down, people in the community will understand and be able to take care of themselves.”

Spring break gave her a chance to go back home, visit her friends, parents and her brand-new nephew. But in between socializing and some “hard studying,” she had a chance to “shadow” a practicing cardiologist at the Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital.

“I had the opportunity to really picture myself in this setting as a future physician. I also sat in patient appointments and witnessed the relationships the doctor can establish with his patients, and the education he can provide, rather than just delivering a diagnosis.”

Of course, she’s got three more years at Berkeley, and then medical school ahead. She recognizes the challenges, but doesn’t seem to doubt she’ll get there.

“I just have to put in the work,” she says.