Robyn Schelenz, UC Newsroom

At a time when gender-affirming care is in the political spotlight — especially in state houses across the country seeking to make it more difficult to obtain this kind of care — we sat down with the leader of one of the most respected transgender and nonbinary health programs in the country, Dr. Maddie Deutsch, to discuss her field.

The UCSF Gender Affirming Health Program Dr. Deutsch runs is a multidisciplinary program that provides evidence-based clinical care for transgender and gender nonbinary communities, conducts research, and trains the next generation of medical providers on all aspects of gender-affirming clinical care.

In this Q&A, condensed for clarity and length, Dr. Deutsch talks about the history of gender-affirming care, her own transition, the needs of her patients, and the challenges she sees in the current political climate for providing these essential services.

Q: How did you get your start in this field?

A: I’m trans and my own personal transition occurred in a range of circuitous, somewhat zigzagging fits and starts between roughly 1996 and 2006.

I initially trained emergency medicine, but I was just getting burned out. I wanted to try to keep people out of emergency departments rather than treating them once they get there.

I came to the realization that there was not much going on in the way of access for transgender people to get health care. I felt like I really understood it not only because of my personal lived experience but because I had basically managed my own transition. I had done a ton of research on a lot of the medical aspects.

I opened up a tiny little office in Los Angeles in late 2006. Things got kind of busy, and before you knew it, I was recruited by the Los Angeles LGBT Center to launch their gender-affirming health program. Over the four years I ran that program, we had hundreds of patients in care. Then I became connected with some people at UCSF and ultimately began to see patients and develop the program that I run now.

Q: What is the process like for patients seeking gender-affirming care?

A: A large chunk of what we do in my clinic is consult with patients who are looking to start hormones. We do a complete medical history and physical exam as appropriate. We talk about a patient’s goals and history, when did they first start thinking about their gender identity, how long have they been thinking about it, what their level of social support is. We look at how to take their individual goals and shape them into something that's medically feasible.

A few weeks later, after a patient has reviewed informational materials, we go over any additional questions that they have and then we talk about starting hormone therapy and we come up with an initial regimen. And that’s how it works for 95 percent of my patients.

For a small percentage of my patients at the second visit, further exploration is needed to clarify goals and we work to connect them to a therapist.

Q: How is the process of seeking gender-affirming care different for minors?

A: If a child is prepubertal, there's no medical treatment that's given. The only decision-making is, do they use their chosen name and pronoun? Do they present themselves with clothing and hairstyle in a different way?

There are specific medical criteria to diagnose different stages of puberty. When a child gets to a stage of early puberty called Tanner stage 2, if the child is still expressing what is called gender dysphoria, or gender incongruence, then, depending on the age of the child and a bunch of other factors, such as family, environment, and so on, and after an assessment that includes an evaluation by a qualified mental health clinician, puberty delaying becomes an option.

I call them puberty blockers, but really they just kind of put the brakes on puberty. It's fully reversible.

At UCSF, the Child and Adolescent Gender Center assists patients with this care. My work focuses on adults.

Q: When is gender-affirming surgery considered?

A: Like any surgery, there are different criteria depending upon the procedure.

Historically these assessments were very like, ‘Are you really trans enough to have this surgery? Prove to me you're really trans,’ and we don't want to do that, although a mental health assessment can be useful, and is sometimes required to align expectations and goals.

What we want to do is make sure the patient is really prepared for the potential for unsatisfactory outcomes or complications. That they have adequate support in place to deal with potential complications and the rigors and demands of self-recovery, which can be months depending on the procedure performed. These kinds of things happen for most surgeries. You go in for weight loss surgery, you’re meeting with a social worker and mental health clinicians to talk about recovery, for example.

We focus on what assessments should look like so that we’re not creating a gatekeeping or stigmatizing environment, but still providing important assessment and preparation so that it centers truly informed consent.

Q: Some people in the United States have trouble accessing this kind of care. What is the importance of this specific care, from a health care perspective?

A: Medically necessary care results in improved lives, improved psychosocial outcomes.

There’s anthropological evidence that transgender identities and people who have a range of gender expansive identities have existed in humanity going back thousands of years. It is a component of human phenotypic expression of behavior and identity and existence.

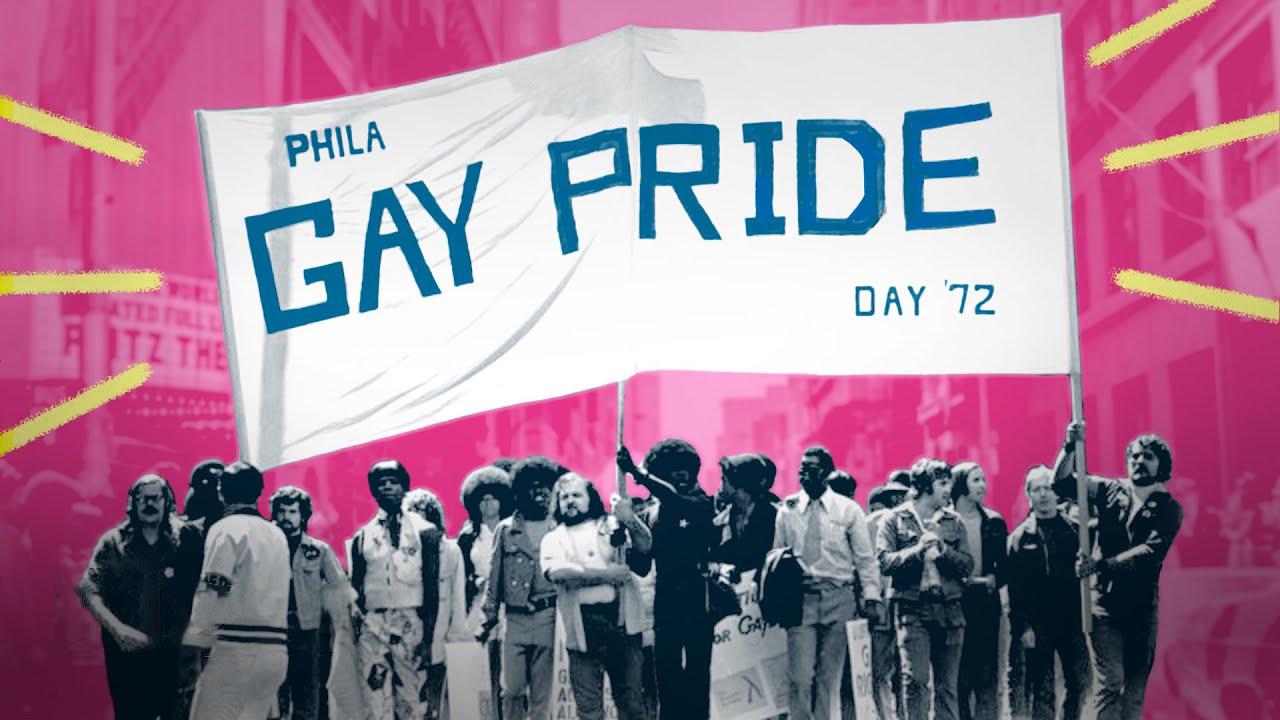

There’s nothing new or cultural about having trans people being part of the human experience. By the 70s, I wouldn't say it was mainstream because societally it was not very visible, but medically it wasn’t particularly controversial. Many academic institutions, large academic medical centers started to develop their own gender programs.

Gender-affirming care is medically necessary. Most major professional societies agree with the designation of this being medically necessary. We don’t have to have a discussion about that.

Sometimes people say, should [insurance] be covering this stuff, is the benefit enough in the cost benefit analysis? That has been studied, and the answer is yes. Hormone therapy is typically a generic medication. The overhead to the health care system of providing hormone therapy is almost zero. Gender-affirming surgeries are for the most part, not very costly, much less so than open heart surgery and less expensive.

Q: Are you seeing more out-of-state people coming to California for care because of the political climate elsewhere?

A: There’s definitely a demand from out-of-state patients on the adult side. For the first couple of years of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a relaxation of the rules around practicing medicine across state lines via telemedicine, due to a lack of access to health care in general. I saw patients from all over the country, in Kansas and Alaska and Texas, who were just like, ‘Oh, this is so great.’

And then the door slammed shut as the rules returned after the initial COVID crisis period. I’m in the process of getting licensed in another state, but it is a very costly and time-consuming process.

For children and adolescents, for a long time the draw here for our UCSF Child and Adolescent Gender Center has been international, with people flying in from Australia and New Zealand for care. That’s the length that people will go to get their kids what they need.

But that group is restricted to those who have the financial ability as well as privilege. It is a huge issue.

Q: Gender-affirming health care has been politicized a great deal recently, especially with kids. Do you think this kind of care is at risk?

A: That’s a difficult question to answer. In the early 2000’s in Los Angeles, when I was in the midst of my own transition, I got thrown out of a bathroom in a restaurant in downtown L.A. That seems like a lifetime ago for people who are in their twenties, but it was not that long ago at all.

What we have is still fragile and is not baked in. I think that as generational turnover continues in this country, the size of that majority who are supportive of these issues will continue to grow. At the same time, there are some very real, politicized threats in states such as Florida and Texas, which are aiming to restrict or even outlaw these treatments altogether on political rather than scientific grounds.

I think that there’s a great deal of structural risk at the federal level that makes it entirely possible that there will be legal difficulty coming for a lot of different groups in this country, including sexual and gender minorities. In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in Bostock that Title IX includes protection around gender identity. But they also recently overturned the Roe V. Wade decision, and as part of the decision, Justice Thomas made comments that suggest this court will consider overturning other precedents as well, should they come before them. Would they turn around and say, ‘No, we don’t think that anymore?’ It is a concerning time indeed.

Q: How are these political pressures affecting people in your field?

A: I have many colleagues in this field who are absolutely living in fear and horror. The people who I work with who do this work across the country are struggling. I have a colleague who is in California who does work with trans kids who had to change her phone number because she got doxed — her private information released to hurt her.

I have colleagues in the southern United States whose program was closed because of this and are now like, ‘Well, what do we do with all of our patients?’ People are really freaking out about this.

This is really about the kids and the adults who need access to this lifesaving care, where multiple studies have demonstrated that gender-affirming care has significant benefit across a range of psychosocial measures for adults and children. There’s no question that these treatments are necessary.

Think of the patients and families. I mean, in Texas, parents are worried that the Department of Children and Family Services will come to their house to take their kids away. Are you kidding? What is the human cost of this?

We’ve got a bunch of people that make up about 1 percent of the country. They are so profoundly stigmatized and discriminated against that they are a completely unempowered group. They’re totally vulnerable. They have no power. Many of them are kids. They can’t do anything. And they are made into this huge boogeyman.

Q: Does this politicization affect you in California?

A: We have a flourishing program here at UCSF on the adult side, as well as the Child and Adolescent Gender Center. I don’t see any state level threat to our programs in California on the horizon. The West Coast, the Northeast, Chicago, I think that programs in these places are safe.

And I think that transpeople here are safe.

The question comes up about what happens if there are federal level actions that start to become more restrictive? For example, if the Federal Aviation Administration were to decide airport bathroom use must be by birth sex. That would impact transgender people’s ability to fly. So I am a little worried about that.

Q: It sounds not unlike what some family planning clinics may be experiencing.

A: They have outlawed gender-affirming care for children and adolescents in several states.

Arkansas actually passed a law to make it a felony to prescribe hormones for kids. And the Republican governor vetoed it after meeting with a trans woman who is an activist and a locally elected official in Fayetteville, Arkansas, among other inputs. She had a meeting with him that turned the tide and brought up all these government overreach issues, like getting involved in medical decision-making between doctors and patients. So the governor vetoed it and the legislature overrode the veto. But a judge has stayed that law for the time being.

But Alabama has actually tried to outlaw it. The Department of Health in Florida has effectively said you’re doing malpractice and Texas has said we’re going to investigate you. It’s scary.

If I was doing work in State A that has been made a felony in State B I’d be very scared. And I’d be looking for my institution to step up and say, ‘We have your back.’

Q: What else would you like people to know about this issue?

A: These are health issues. These are issues that affect the health of people and that affect our society. The University of California is one of the most powerful institutions on this planet. And as goes the University of California, often goes the rest of the world.

I don’t want to politicize. I don’t want to tell people how to vote. But people do need to be aware of the issues, the actual science behind them, and then keep this in mind as they get out and vote in local, state and federal elections.