Carol Ness, UC Berkeley

A UC Berkeley graduate student in optometry, one of her professors and a Berkeley alumnus have joined forces to build a long-distance diagnostic project that has the potential to keep a large number of people in crisis-torn Libya from going blind.

The public service project involves training Libyan doctors to take detailed digital photographs inside patients’ eyes, of their retinas, as part of routine health care and put the images online for remote diagnosis of damage caused by diabetes before it’s too late. Too often, diabetes-related retinopathy isn’t caught until it causes symptoms, when treatment can no longer save vision.

The first 11 Libyan doctors underwent training for three days in February in Istanbul, in a seminar organized by the Avicenna Group and taught by Berkeley optometry professor Jorge Cuadros. Turkey was chosen as the training site for security reasons and because it is easily accessible from Libya.

If all goes according to plan, many more doctors will be trained over the next year, both in Libya and out — all because of a project that developed rapidly from a seed planted in a Diabetic Health Clinic class in Berkeley’s School of Optometry.

In the class, Cuadros taught students how to analyze photos of diabetic retinopathy as part of EyePACS, the California-based online initiative he co-founded to train people working in diabetes care to screen patients’ vision for remote diagnosis by certified eye doctors.

Family connection

In his class was third-year optometry student Fatima Elkabti, who knows firsthand the toll that diabetes is taking in Libya, where the disease is rampant but greatly underdiagnosed. Elkabti’s father, a Libyan, has diabetes, as do about half of her many aunts and uncles.

“I walked out of the class and asked Dr. Cuadros, ‘Can we do this in Libya?’ “ Elkabti relates. Do some research, the professor told her.

Elkabti got to work and within an hour found Ethan Chorin, who earned his Ph.D. at Berkeley in 2000, served in the U.S. diplomatic corps in Libya from 2004 to 2006 and has published a book about the recent Libyan revolution. He founded the not-for-profit Avicenna Group in 2011 with a Libyan-American colleague to catalyze health-related partnerships between Libyan organizations and U.S. universities. Traveling back and forth between Benghazi and Berkeley, he looked for ways to involve Berkeley in Libya’s reconstruction efforts.

“I shot Ethan an email, and within hours we were talking about how to make this happen,” Elkabti says. The Berkeley-Libya retinopathy project was off and running.

Diabetes-related retinopathy is one of the leading causes of blindness in Libya — as well as in the United States and in much of the world. EyePACS has brought retinal screenings to poor and medically underserved areas from California’s Central Valley to Peru, and the Libyan retinopathy project extends the concept to politically unstable and dangerous regions.

A survey in 2009 found that 16.4 percent of Libyans had diabetes, an estimate considered low, according to Chorin, who was in Benghazi during the 2012 attack that killed U.S. ambassador Christopher Stevens, also a Berkeley alumnus. The project aspires to screen 30,000 Libyans, and treat the estimated 5 to 10 percent of them who have operable retinopathy.

Seizing opportunity

Elkabti, a Fulbright scholar who has worked on a Lions Club vision-screening mission in Mexico and is heading to Peru soon on a second one, saw Libya as ripe for telemedicine. “Libya’s health care system is terrible,” she says, and people — if they have the money — fly out of the country for care. She considered practicing there herself after she graduates, but realized that training people already there could have a bigger impact.

“I can’t help them as much as they can help themselves,” says Elkabti, who grew up in Southern California and has visited Libya three times.

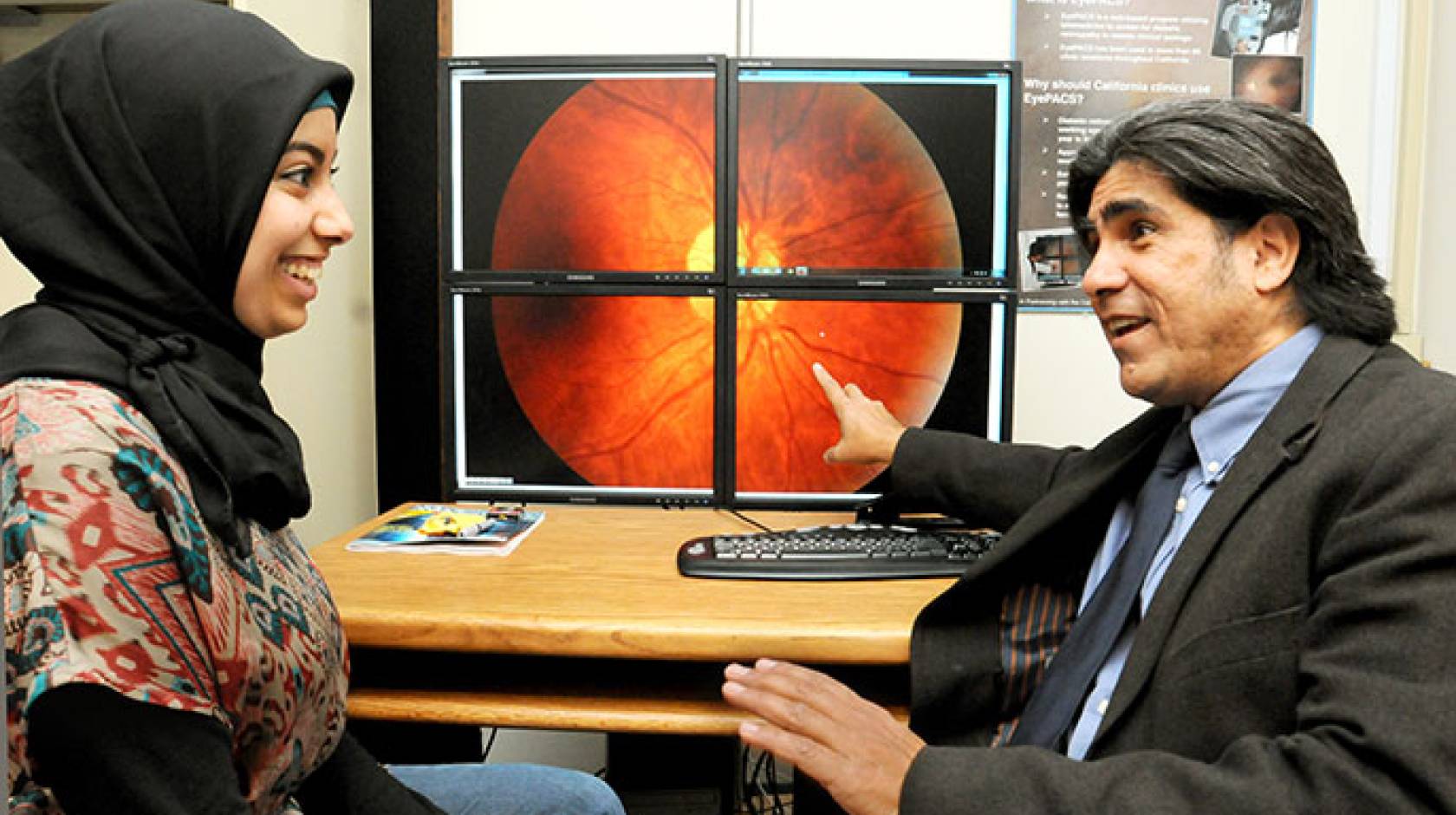

Cuadros, as part of EyePACS, has traveled far and wide to teach doctors to use cameras that can capture retinal images far more detailed than a cellphone can take, and to grade what they show. From an office on the ground floor of Minor Hall, he can call up any of the 250,000-plus images in the EyePACS database to train optometry students in the diagnosis of retinopathy.

A retinal image enlarged to fill four adjacent monitors reveals branching red blood vessels circling the bright yellow optic nerve. Retinopathy shows clearly as blotches of leaked blood and weak extra veins. Laser treatment, seen in some of the images, destroys the damaged vessels, preserving the health of the rest of the retina.

By summer, the first retinal images from Libya are expected to start flowing into the database. The images will be graded and diagnosed by the 11 doctors trained in Istanbul, all of whom earned their certification during the seminar. But they’ll also be visible at Berkeley, where Cuadros, Elkabti and others involved in the project will provide diagnostic backup and quality assurance.

Changes after the Arab Spring

Chorin, who earned his doctorate in resource economics in Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources, says he believes the project could be a model for post-conflict operations in other Arab Spring countries.

“Despite the very difficult operating conditions in places like Libya and Syria, it is still possible to have an impact, particularly in the field of health, and through a combination of remote assistance and targeted support,” Chorin says. Committed local partners are essential, he says, adding that more than half the funding for the retinopathy project came from commercial sponsors in Libya.

In addition to the retinopathy project, Chorin’s organization, Avicenna, supports a number of partnerships with UC campuses, including the Beahrs Environmental Leadership Program in Berkeley’s CNR, which had its first Libyan fellows last summer.

In Libya, the retinal cameras are being bought now, says Chorin — one each for Tripoli, a rural village and the small city of Kabaw. He is coordinating the project from Berkeley.

For Elkabti, who plans a trip to check in on the project in December, says the telemedicine project is perfect for post-revolution Libya.

“It’s a country in transition, and it’s hard to build a house on a moving river,” she says. “The screening program, though, is like a raft — it’s minimalist by nature, durable by design. The few things it needs, Libya has.”

When the first images from Libya go up online, Elkabti, who is now certified and will wrap up her degree next spring, will be ready to plunge in — from Berkeley, or wherever she is. “I’m excited,” she says. “I’ll be able to help.”