Nicole Freeling, UC Newsroom

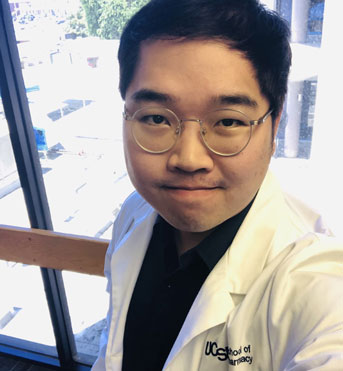

UCSF pharmacy student Min Ku Choi remembers the day in June 2012 when his phone blew up with messages from friends and family.

President Obama had just announced a new program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). It would provide people like Choi, undocumented and brought to the U.S. as a child, the opportunity to live and work legally in the U.S. for a renewable two-year period.

At the time Choi was the only one in his family not to have legal status, and he was struggling to create a life for himself. “It was like until then, nothing had been possible for me, and then the next day, all of a sudden, there was hope,” Choi said.

As a teenager, Choi moved from South Korea to Los Angeles with his parents, who had come to the U.S. for work with plans to apply for legal residency. Choi adapted well to his new home, graduating as a top student from Palisades Charter High School and enrolling at UC San Diego to study chemistry.

By the time his family’s application for a green card was finally processed, however, Choi was deemed ineligible under his parents’ application because he was no longer a minor. With his temporary visa now expired, Choi dropped out of school after freshman year and returned to Los Angeles, where he worked under the table, tutoring local kids in math and science.

On the side, Choi continued studying biochemistry, in the hope that one day he would be able to complete his education.

His opportunity finally arrived five years later, when DACA was established.

“DACA was a shining beacon of light for me,” he said. “Although it was imperfect, it was everything.”

He got his driver’s license, applied for a work permit, and — with the possibility of legal employment — was also able to restart his education, enrolling at Santa Monica College.

Although he never completed a formal undergraduate degree, he ultimately earned enough credits, in conjunction with his year at UC San Diego, to apply for and be accepted into UCSF’s School of Pharmacy.

“It was a long journey, but it was worth it,” he said.

Now he is in his fourth and final year of pharmacy school, with about four clinical rotations to go before he qualifies for his license. He is due to sit his board exam in May and graduate in June, just as the Supreme Court is expected to rule on DACA’s fate.

Choi believes his bilingual ability will make a big difference for Korean residents in his Los Angeles community, where the language barrier can make it hard for patients to access care.

Yet after the long journey it took to complete his education — and the second chance he was given when DACA was established — Choi fears he will find himself right back in the situation he was mired in a few years ago: with all the smarts, work ethic and valuable training one needs, but no way to put those skills to work.

“I will need to repay my student loans, but I will have no means to do so, and no hope of gaining legal status. The uncertainty is dreadful. It takes a huge physical and emotional toll,” he said.

For now, Choi is pushing ahead just as he did the first time around, continuing with his studies in the hopes that those efforts will eventually pay off.

“A pharmacist is the most accessible and approachable person in the health care profession. They are able to make an impact in everyday people’s lives,” Choi said.

“That is my dream. The only thing hindering me is my status.”