The plume of steam from UC Berkeley's natural gas-fired power plant is a familiar sight on the skyline of San Francisco's East Bay. But the facility's days are numbered: The campus is on track to switch to an electrical heating system by 2028. As each UC campus prepares to publish its long-term plan for eliminating carbon emissions and transitioning to renewable energy, hear from sustainability experts on three campuses — Davis, Berkeley and Santa Cruz — that are phasing out fossil fuels ahead of schedule.

Chancellor Cynthia Larive was barely a year into her tenure at UC Santa Cruz when a fast-moving wildfire nearly destroyed the campus. “It came to within a mile and a half of us. Everyone had to evacuate,” Larive recalled recently. “And if the wind hadn't shifted overnight, I likely wouldn't be talking to you from this office. The fires could have burned through campus to the sea.”

That terrifying Aug. 2020 incident — during one of California’s worst wildfire years in history — hardened Larive’s resolve to make climate change a top priority of her administration.

“I came to UC Santa Cruz with an understanding that climate change is something we need to deal with immediately. And even since then, the climate impacts our campus and our community have felt have been pretty profound,” Larive said.

As communities throughout the Santa Cruz mountains recovered from the fires, Larive asked her staff to develop a plan for cutting campus carbon emissions to zero by 2030.

The resulting plan, published in October 2023, spells out the steps the campus needs to take to decarbonize and electrify its energy systems. Today many of the campus’s buildings are heated by natural gas-powered boilers and furnaces, and its electricity is generated by an on-site natural gas power plant or delivered by PG&E through the grid. The decarbonization plan calls for replacing these disparate systems with centralized power stations powered by renewably generated electricity. UC Santa Cruz will also consider how to swap in clean fuels for the natural gas that runs its power plant, which currently generates about two-thirds of the campus’s total carbon emissions.

At Chancellor Larive’s urging, UC Santa Cruz’s plan includes a pathway to completing the transition by 2030 (a date the Chancellor describes as “an ambitious goal”), along with scenarios for decarbonizing by 2035, 2040 and 2045.

UC's climate goals: carbon-free by 2045

Larive is not alone in taking urgent climate action. UC Berkeley at the direction of Chancellor Christ and UC Davis under Chancellor May’s leadership have already begun transitioning their campuses from fossil fuels toward cleaner sources of energy. And UC’s new climate policy, adopted in July 2023, commits the entire 10-campus system to eliminating greenhouse gas emissions by 2045, aligning the University with the State’s target date for net zero carbon emission.

“Each campus will set their own schedules to drive the transition away from fossil fuels,” explains David Phillips, associate vice president for energy and sustainability at UC Office of the President. “Chancellors Larive, Christ and May are trailblazing what’s feasible, and their fellow chancellors will set their campus’s public goals later this year, informed by site-specific studies funded by the State of California.”

Each of these campuses has different challenges and considerations as they transition to renewable energy, but they have a few important things in common: committed leaders building teams who embrace the challenge, staff and faculty with deep expertise in engineering, climate science, sustainability and social transformation, and an energized community of activists pushing for urgent change.

“This kind of transformative change doesn’t happen spontaneously. The University has a smaller carbon footprint today because of the ambitious goals it set in the past, and because our community came together to meet those goals,” said UC President Michael V. Drake, M.D. “As we grapple with a worsening climate crisis, we’re raising the bar once again. Progress like we’re seeing at Davis, Santa Cruz and Berkeley is proving that decarbonization is both necessary and possible.”

UC Davis makes a Big Shift

At UC Davis, the transition to green energy is already well underway. A year ago, crews finished the first phase of what’s known around Davis as the Big Shift, replacing the campus’s natural gas-fired steam apparatus with a system that can use electricity to generate hot water instead. During two years of construction, crews dug great big trenches through the heart of campus, laying four miles of new pipe and swapping out steam heating systems with those that run on hot water in 31 buildings.

For the time being, Davis is burning fossil fuels to heat the water that’s running through the new pipes. But once all the buildings that are connected to this centralized heating and cooling system have been retrofitted, they’ll be able to shut down the natural gas-powered boilers and run the whole system on electric heat pumps. Altogether, the project will shrink Davis’s carbon footprint by 80 percent.

Davis leads UC campuses in decarbonization today in part because this transition has been in the works for 15 years, says Joshua Morejohn, Davis’s executive director of utilities and engineering. Back in the aughts, “our steam system was 50 years old and going to need to be renewed,” Morejohn explained. In studying alternatives, they found that sticking with steam, which is volatile, expensive and inefficient, was actually going to cost the campus way more money in the long run.

“We cobbled together all the near-term steam projects in the budget, which got us about $50 million. So we said, ‘Let's spend that $50 million on the first phase of a hot-water system that could eventually run on zero-carbon energy,’” Morejohn says.

Decarbonizing UC — not to mention the rest of our economy — in time to avoid complete climate catastrophe is going to take a lot of these kind of “big cultural shifts,” says Ellen Vaughan, assistant director of sustainability for operational and strategic initiatives at UC Santa Cruz.

“You might be able to find 90 percent of the cost of an electrification project in the budget that’s already been allocated for fossil fuel infrastructure replacement. You just need to realize and be excited about the fact there is an opportunity to electrify, and that you don’t have to replace a natural gas boiler with another natural gas boiler.”

How decarbonization supports UC’s teaching, research and public service mission

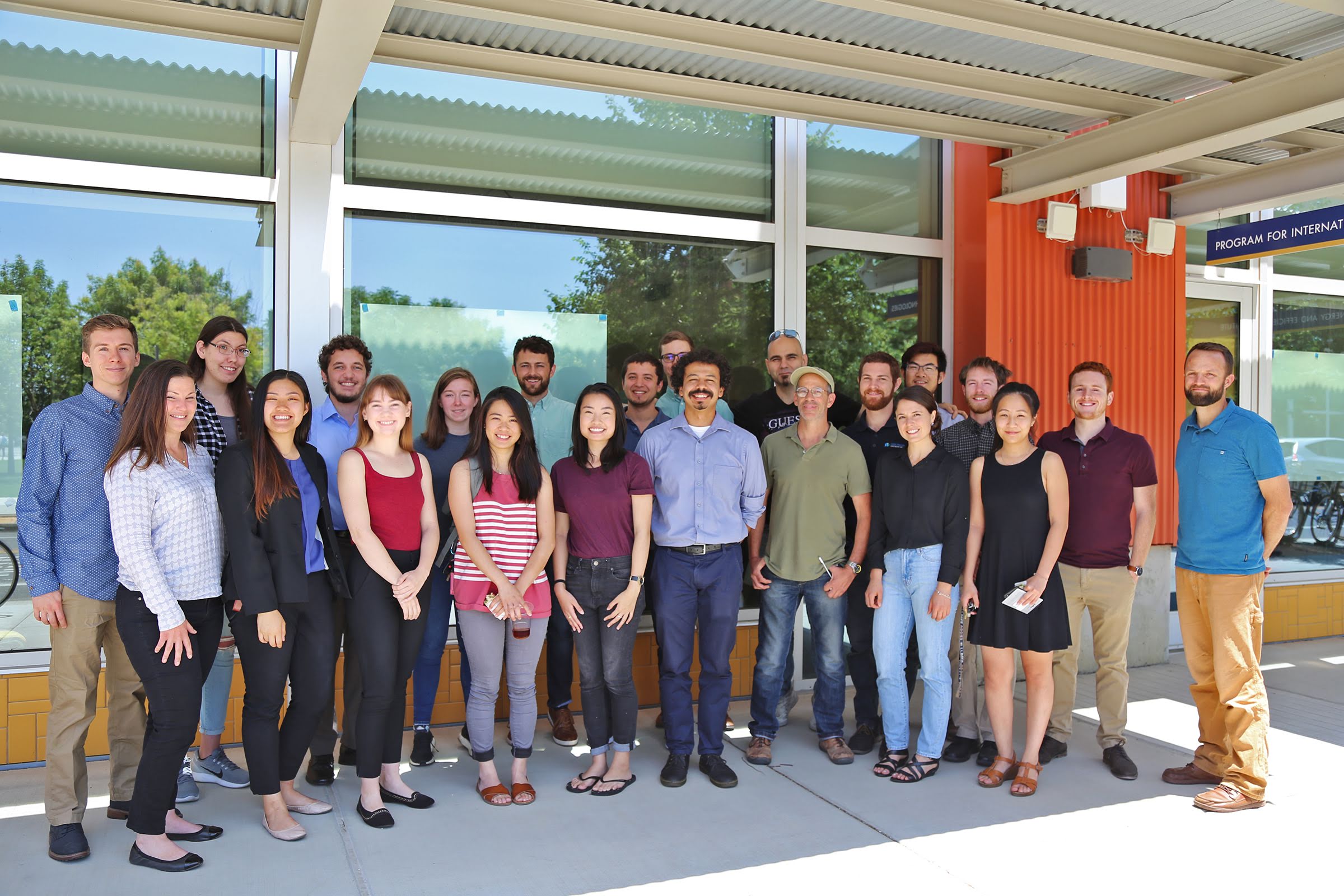

The three UC campuses leading the green transition have drawn on the collective brainpower of thousands of students and faculty to generate the most efficient, effective and equitable solutions for each campus. Along the way, they’ve generated valuable new scientific insights while providing hands-on educational opportunities for the next generation of climate leaders.

“Climate change is totally an interdisciplinary problem, so it makes sense that we’d go after it with multidisciplinary groups,” says Kurt Kornbluth, assistant professor of biological and agricultural engineering at UC Davis. For the past dozen years, he and Morejohn have co-taught a project-based class called Path to Zero Net Energy. Students with backgrounds in everything from engineering to classics have worked together to audit campus building energy use, generate new algorithms for managing water use on campus and even develop the business case that Davis is using to fund the transition from steam to hot water and climate-warming fossil fuels to renewably generated electricity.

Kornbluth and Morejohn also co-lead a campus-backed initiative called Sustainable Campus Sustainable Cities, which casts UC Davis as a living lab for research and education focused on eliminating UC Davis’s carbon emissions. Each year, the initiative hosts a workshop connecting sustainability leaders at colleges and universities around the world.

“On a lot of these issues, our students are the ones doing the consulting for the campus, instead of us having to hire someone from outside. I can use these projects as a springboard for my own research as a professor. And students are getting amazing experience, and they all get great jobs after graduation,” Kornbluth says. “The faculty benefits, the students benefit, and the campus benefits.”

Putting clean tech to the test at UC Berkeley

By using UC campuses as living labs, researchers and students are also generating solutions that will power the green transition across California and beyond. At UC Berkeley, this dynamic is playing out in an unassuming patch of dirt in a side yard of the chancellor’s residence, University House.

UC Berkeley is currently in the design phase of its Clean Energy Campus initiative, a complete reconstruction of the campus’s energy system that will cut building-related energy carbon emissions by 85 percent. If all goes accordingly, by 2028 the campus will replace an aging natural gas-burning power and thermal plant with an electrified heat pump and chilled water system. Plans also call for enough solar panels, hydrogen fuel cells and batteries to power the campus’s critical systems when the utility grid goes down.

“We’re taking a whole campus and transforming it. It’s a giant project,” says Kira Stoll, UC Berkeley’s chief sustainability and carbon solutions officer. “We're building a thermal plant, we're digging up hundreds and hundreds of feet of ground, we're running miles of piping. And we’re turning off a very stable, known energy source and moving to a symphony of technologies that have all been used before, but not quite in this way. It's going to work, but there are not a lot of examples of anyone else out there of doing it.”

And that patch of dirt outside University House? It’s the site of research led by engineering professor Kenichi Soga, who wondered whether the campus could make use of stable year-round temperatures underground to help heat pumps operate more efficiently. No one knew whether the rock under Berkeley’s campus would be soft enough to drill into, or hard enough to hold its shape, or made of the right stuff to disperse heat efficiently. So Soga’s team hauled out a drill rig to dig the deepest hole ever dug on Berkeley’s campus: 400 feet into the bedrock.

The results were promising. “It’s good rock: not too hard, not to soft,” Soga says. “It's easy to drill, and we measured the heat dissipation from the borehole into the ground and we got good efficiency for the ground-sourced heat pump.”

The campus is putting Soga’s findings into immediate use: they plan to dig a whole grid of geothermal boreholes underneath the future thermal plant. Meanwhile, Soga is at work on a new project, studying whether heat sent into boreholes in the summer can be stored until winter, when it can be pulled back up and used to warm residence halls, labs and classrooms.

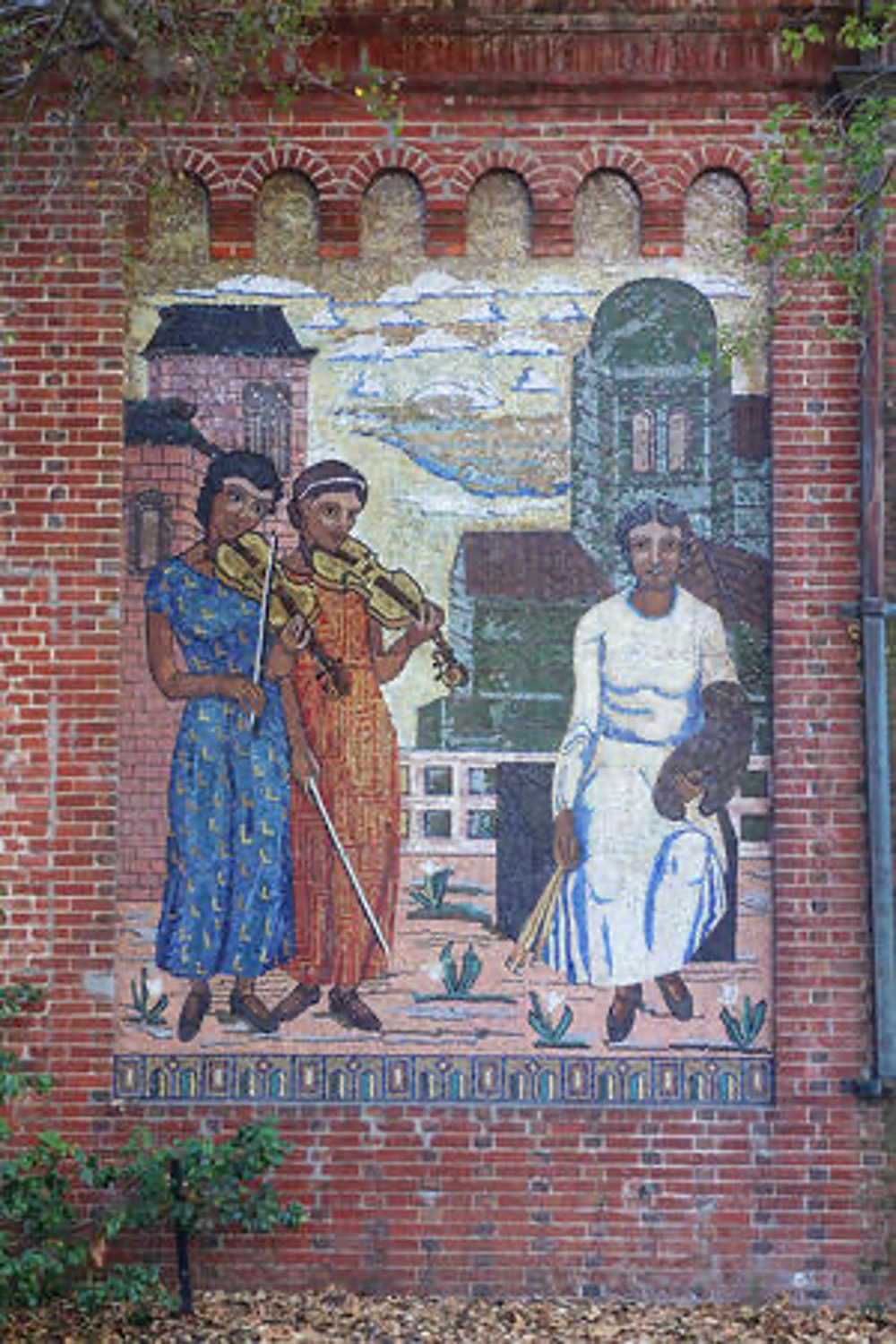

This mosaic by Florence Alston Williams Swift, a WPA federal art project from 1936-1937, adorns the side of a historic UC Berkeley building that will become the switching station for the new clean energy system.

Future focused

These days, you’d be hard pressed to find UC staff, faculty or students who think the University should carry on burning fossil fuels for the foreseeable future. Kornbluth attributes the progress Davis has made to a campus-wide spirit of research-based decision-making, and the fact that “everyone is on the same page” about both the urgency of the transition and the fact that it’s imminently achievable.

What’s more, research by Kornbluth and Morejohn’s students have helped make the case that decarbonization will actually save money in the long run. But how to cover the costs of the transition up front — which estimates put in the high hundreds of millions of dollars for each campus that’s studied it so far — remains an open, vexing question.

Fortunately, taking on vexing questions is something of a stock in trade across the University of California. “We're a leading institution of higher education,” says Stoll. “The amount of expertise that we have, researchers from all kinds of disciplines, and the ability to use our research capabilities for understanding future technologies and opportunities, it’s phenomenal.”

Chancellor Larive agrees.

“You can't be daunted by big hurdles. If we only focus on the fact that the climate is changing, it's very depressing,” says Chancellor Larive. “We have to think about what proactive things can we do. And that’s what we’re doing.”