Jason Pohl, UC Berkeley

Carolyn Smith knew she had a lot to learn when she arrived on the banks of the Klamath River 15 years ago. That summer, tribal elders taught her the cultural significance of hand-woven baskets and how to gather materials that can be formed into containers and passed from one generation to the next.

She also learned firsthand that it’s OK if one’s first basket looks more like a bird’s nest.

The experience has had a lasting effect on Smith, an enrolled descendant of the Karuk tribe who is a new faculty member this semester in UC Berkeley’s anthropology department. Ever since, Smith has committed much of her life — including her doctoral work — to understanding and explaining the art and significance of Indigenous baskets.

"I never imagined how that trip would change my life," Smith said. "I didn't grow up on the river. I didn't grow up with my culture. I didn't really have a full understanding of the magnitude of how intertwined our basket weaving culture is with our language, with our life, with our histories, with our families, with our food, with our river."

While her job at Berkeley is new, she’s anything but new to the campus. Smith graduated from Berkeley in 2017 with a Ph.D. in anthropology. She’s also been part of the Native community at Berkeley that works on high-profile initiatives — including the campus’s effort to repatriate human remains to tribes.

Outside of Berkeley, Smith has led the California Indian Basket Weavers’ Association and helped create a Native youth substance use disorder prevention program for the Northern California Indian Development Council.

This semester, Smith is teaching an anthropology course on museum methods. She’s using it as a chance to talk with students about Berkeley’s troubled past on Indigenous issues and recent positive steps here and at other institutions nationwide. Acknowledging the past is essential for a better future, she said.

"While there is absolutely more that needs to happen," Smith said, "there are avenues now to create the changes that need to happen."

Berkeley News spoke with Smith about her Karuk ancestry, learning and teaching at Berkeley and the enduring significance of basket weaving.

Berkeley News: You’ve devoted much of your academic and personal life to Karuk basket weaving. How did you become interested in it?

Carolyn Smith: The way I got into basket weaving was from my sister, Susan Gehr. As soon as she graduated from college, she moved up to the Klamath River, worked in fisheries and, later, in the language program. She ran our language program for our tribe for several years and helped write the dictionary for our tribe. Susan is an advocate for language revitalization.

While she was up there, she was saying, "You have to come up here. You have to learn how to weave baskets." I've always made jewelry and a variety of other things, but she said basket weaving was something I should learn. I came up and stayed with her and got to meet Wilverna Reece, who is my basket-weaving teacher and one of my very close friends. Verna is a Karuk elder and master basket weaver who has been weaving since the 1970s.

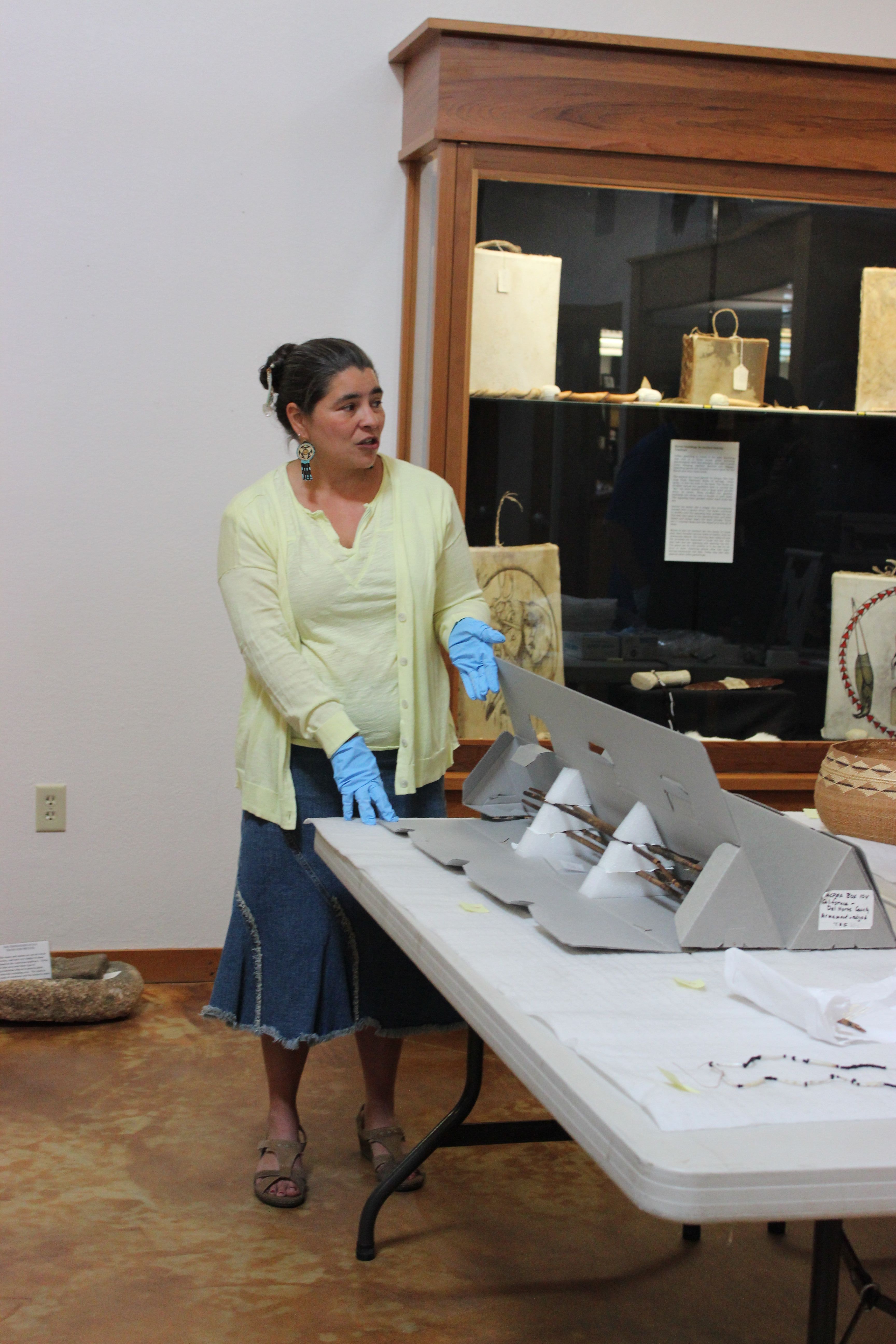

In her class, Carolyn Smith speaks about acknowledging the past while also embracing a future rooted in community partnerships that can shape a new future for museums.

The very first basket I wove with Verna was at one of our Karuk Basketweavers gatherings. I didn't know what I was doing. I was frustrated. It was something so different for me to work with. I didn't know the materials. I showed it to her, and she said, “Well, that looks like a great bird's nest!" So that was my introduction to basket weaving.

But I kept coming back, spending as much time as I could with her to gather materials and learn more about where, what and how we gather basket weaving plants. I got better and better at weaving, but I still consider myself a beginner.

I've been doing this for over 15 years, but it is difficult because I am disconnected from my weaving community. I work really hard to go visit and stay with her and visit my friends and my other weaving teachers up there as often as I can.

What made you want to pursue basket weaving academically?

I started out at Santa Rosa Junior College, and I ended up with a degree in humanities. I couldn't pick a major because there were so many art classes and philosophy classes that I was really engaged in. Eventually, I did have to graduate and move on. So I transferred to Sonoma State and majored in anthropology.

At Sonoma State, I was also a McNair Scholar. My project was on Karuk basket weaving, and I interviewed Verna and took as many basket weaving classes as possible. Working with her sparked my passion for learning as much as I could about weaving. I wanted to continue this work in graduate school.

I never dreamed I would be able to make it to Berkeley. It just seemed completely out of my reach. And it was one of the schools that I got into. I'm like, 'This is the place.' Despite a really painful legacy here at Berkeley, it was the appropriate place for me to be.

During your Ph.D. work, how did your appreciation of the practice change? Did adding this academic lens to the cultural practice affect your understanding of it?

It deepened my connection to my craft. Being able to spend time on the river and having the opportunity to talk with other weavers about their practice, I learned how basket weaving is more than just a practice or an art or a craft. It's a way of life. It's a way of living and being in the world. It's a way of seeing the world. It's a way of knowing the world.

Karuk baskets are living beings. I began to understand what that meant as I was able to talk with more people and be able to focus on my own weaving. There's this aliveness, and there's this vibrancy of baskets, and they're very much social beings in our communities.

They hold our history. They hold our language. They tell us about our ontology, our epistemology, our cosmology. They don't just hold our history of what our past practices were. They hold our history — even the painful eras of our history. It really brought me closer to the connections of baskets.

In much of the older anthropological literature, I did not see the vitality of Karuk basketry reflected. Certainly, there were descriptions of the materials, techniques, designs, types and uses of baskets. But the resonance of basket weaving as a way of living and being was missing.

This was my frustration and my drive to continue my research because when Karuk baskets are researched solely as physical things, it creates a fracture in the knowledge that each basket holds and ignores their inherent beingness. It denies their eminence.

Was it difficult doing this work while affiliated with a university that, as you said, has a painful legacy regarding Indigenous people and practices? How has this affected you?

Doing this in an academic space, there's some cognitive dissonance. When I conduct research in museum collections, it is difficult because our baskets are disconnected from their home on the Klamath River and from their people. Each one of those museum visits is painful. The baskets are not living their purpose, or they're in there in such despair or disrepair that they need to be put to rest.

Carolyn Smith wove this basket in 2020. The white is bear grass; red is alder bark-dyed woodwardia fern; brown on the left is spruce root; and the warp of the basket is made with hazel sticks.

If we think about baskets as a living thing, they're created, they're born. They live their purpose. And then they're meant to go to rest. They're meant to be laid back in the earth or burned. And seeing some of these baskets that have been there for over 100 years that have never visited with their people, never been around with people, never been exhibited, can be quite painful.

It is not lost on me that I am associated with a university and a department that has played a large part in removing belongings and ancestors from their homelands. It is something that I wrestle with often.

Through my research though, I work toward destabilizing the historic, colonial legacies of ethnographic museum collections and the racist paradigms that informed early anthropologists and other collectors.

Our tribe has definitely had those painful entanglements with the Hearst Museum. And certainly, for me as a student here, the more that I've learned, it's infuriating. There are more Native American ancestors on this campus than there are students, faculty and staff. Honestly, it can be very difficult.

But I've seen change. I've been a part of the change. It is part of the work that I do and part of the work that I feel responsible for as a person here. I need to help facilitate or help in any way that I can.

You live in Sonoma County. How did your family arrive there?

My grandmother was born in our tribal territory, in Happy Camp in Northern California, near the Klamath River. When she was a young girl, she was sent to boarding school in Oregon at Chemawa Indian School. She was then sent to Fort Lapwai in Idaho because she had contracted tuberculosis — it was a sanatorium for Native American children coming from boarding schools.

She never really went back home but had crisscrossed Northern California, eventually settling down in Sonoma County. That's where my dad and my mom met.

When you pack up the car and drive north to the Klamath now, is it like you’re coming home? Or like you’re leaving home?

It absolutely feels like I'm coming home. As much as Sonoma County is like home — because it's where I grew up, and that's where I have my connection to my grandma, who passed awhile ago, and my dad and my stepmom still live there on the family property — I feel myself when I'm on the Klamath.

At the Karuk Tribe People's Center, Carolyn Smith helped evaluate items that had been repatriated from a county historical society. The items had to be tested for heavy metals and pesticides that they may have been exposed to over the years.

Did your interest in making jewelry come from your grandmother?

My grandmother taught me how to sew, and she taught me how to crochet and do needlepoint work and embroidery. I feel that my grandmother nurtured my creativity. My interest in jewelry-making developed in high school, though. I took an art class where we actually learned how to do silversmithing.

Later on, when I was learning how to weave baskets, I was also learning how to use our traditional materials, like pine nuts and dentalium shells and abalone and cedar berries and other materials that are used in our regalia, to make jewelry. It just felt like something that I was coming home to. Most of the jewelry I make now is with our traditional materials.

Tell me about the materials-gathering part of all of this. It sounds like quite a process.

I'm working with Verna on a series of self-published books about gathering materials.

Wilverna very much feels the responsibility to ensure that future generations of basket weavers have the knowledge to be able to go out and gather their own materials. That's one of the difficulties. People are more than happy to learn how to weave and really want to. It's such an important part of who we are. And it's an important part of the connection.

Gathering weaving materials and preparing them for weaving is almost 90% of the process for weaving. It's not easy to know what to look for, where to go, how to be able to tell that the materials that you're gathering are going to be good for your basket.

Considering Berkeley’s history and your experience, what do you hope students take away from your class? How do you hope it affects the future — of museums and of anthropology?

Our languages were collected. Our lifeways and histories were collected, and academic careers were built upon these knowledges. Ceremonial information was collected. Our bodies were stolen from their gravesites. And our cultural patrimony, our sacred objects, were taken and stored in museum storage.

I want my students to understand this legacy. I want them to understand the roots of museum anthropology and how the field has made progress, but also the need for additional work.

During a gathering trip for basket weaving materials, Carolyn Smith collected a bundle of willow sticks. It's one of her favorite photos, she said, because it "reminds me how joyful and incredible it is to go gathering with my friends and be out there on the river."

One of the things that I stress to my students is that it’s important to develop collaborative community partnerships in research.

As future museum anthropologists, I stress that they have a responsibility to the communities, to the people, whose belongings are stewarded by museums. They need to make a commitment to build relationships that are rooted in transparency, accountability, shared authority, repatriation and rematriation, and trust.

Our histories and these histories of academia can't be shrouded in secrecy anymore. It absolutely has to be transparent. We have to shine a light on the painful legacy of the field of museum anthropology so that there can be remediation and reconciliation.

This legacy has caused so much harm in our communities, and this wound will always be there because we cannot reverse the past. Yet, there is potential for partnerships that can shape a new museology rooted in decolonizing and indigenizing museums.

In her museum methods class, Carolyn Smith speaks about addressing the past while embracing a future rooted in community partnerships that can shape a new path for museums.