Jules Bernstein, UC Riverside

Researchers at UC Riverside are paving the way for diabetes and cancer patients to forget needles and injections, and instead take pills to manage their conditions.

Some drugs for these diseases dissolve in water, so transporting them through the intestines, which receive what we drink and eat, is not feasible. As a result, these drugs cannot be administered by mouth. However, UC Riverside scientists have created a chemical “tag” that can be added to these drugs, allowing them to enter blood circulation via the intestines.

The details of how they found the tag, and demonstrations of its effectiveness, are described in a new Journal of the American Chemical Society paper.

The tag is composed of a small peptide, which is like a protein fragment. “Because they are relatively small molecules, you can chemically attach them to drugs, or other molecules of interest, and use them to deliver those drugs orally,” said Min Xue, UC Riverside chemistry professor who led the research.

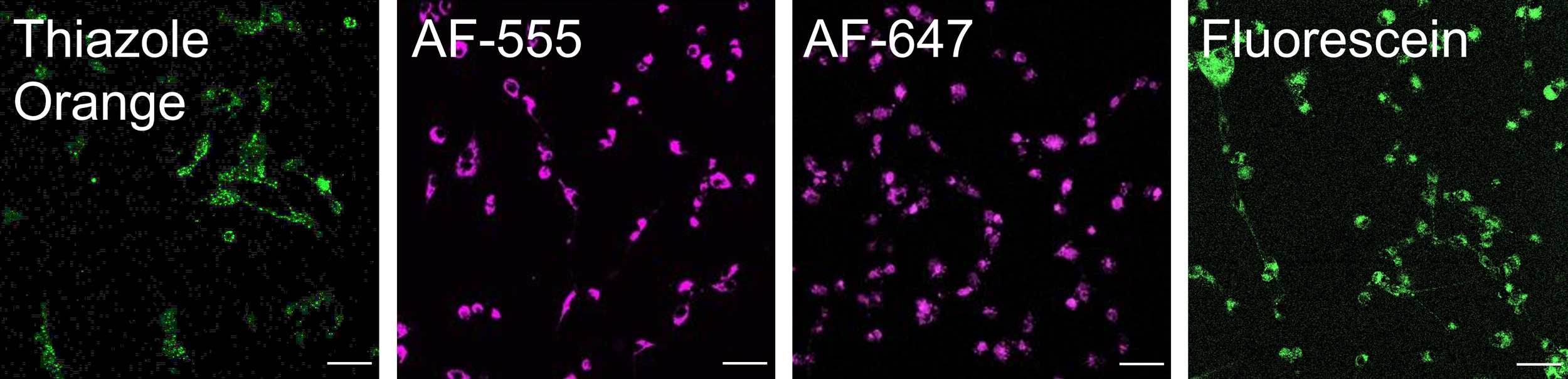

Xue’s laboratory was testing something unrelated when the researchers observed these peptides making their way into cells.

“We did not expect to find this peptide making its way into cells. It took us by surprise,” Xue said. “We always wanted to find this kind of chemical tag, and it finally happened serendipitously.”

This observation was unexpected, Xue said, because previously, the researchers believed that this type of delivery tag needed to carry positive charges to be accepted into the negatively charged cells. Their work with this neutral peptide tag, called EPP6, shows that belief was not accurate.

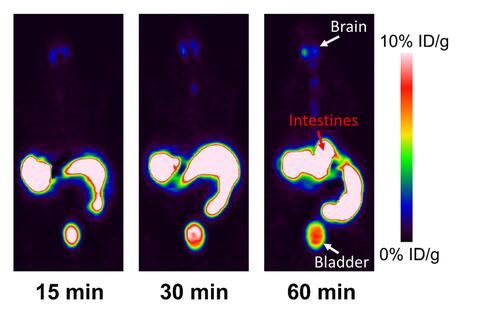

Testing the peptide’s ability to move through a body, the Xue group teamed up with Kai Chen’s group in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California and fed the peptide to mice. Using a PET scan — a technique similar to a whole-body X-ray that is available at USC, the team observed the peptide accumulating in the intestines, and documented its ultimate transfer into the animals’ organs via the blood.

Having proven the tag successfully navigated the circulatory systems through oral administration, the team now plans to demonstrate that the tag can do the same thing when attached to a selection of drugs. “Quite compelling preliminary results make us think we can push this further,” Xue said.

Many drugs, including insulin, must be injected. The researchers are hopeful their next set of experiments will change that, allowing them to add this tag to a wide variety of drugs and chemicals, changing the way those molecules move through the body.

“This discovery could lift a burden on people who are already burdened with illness,” Xue said.