Jason Pohl, UC Berkeley

Few plants are more celebrated in Egyptian mythology than the blue lotus, a stunning water lily that stars in some of archaeology’s most significant discoveries. Researchers found its petals covering the body of King Tut when they opened his tomb in 1922, and its flowers often adorn ancient papyri scrolls. Scholars have long hypothesized that the lilies, when soaked in wine, release psychedelic properties used at hallucination-and-sex-fueled rituals dating back some 3,000 years.

Perhaps, then, it’s not surprising that a plant resembling the blue lotus is now marketed online as a soothing flower, one that can be smoked in a vape or infused in tea.

There’s just one problem, according to Liam McEvoy: The blue lotus used in ancient Egypt and the water lily advertised online are completely different plants.

McEvoy, a fourth-year UC Berkeley student majoring in anthropology and minoring in Egyptology, has spent much of his time on campus studying Nymphaea caerulea, the vaunted Egyptian blue lotus. He’s dived deep into the wild world of rare plant procurement on Reddit to look for the plant in the present and studied hieroglyphic translation to search for it in the past. In collaboration with the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics and with the help of chemists, he compared authentic plants now growing at the UC Botanical Garden with samples sold in online marketplaces like Etsy.

Not only are the plants from ancient Egypt an entirely different species from those sold online, McEvoy said, but Egyptologists for decades may have misunderstood how the psychoactive blue lotus that grew on the Nile River banks was consumed thousands of years ago.

“I knew from the very beginning this was going to be my Berkeley thing,” McEvoy said. “I wanted to let the plant tell its story and contribute to a discussion where there’s all this pseudoscience floating around — pseudoscience that makes some people a lot of money.”

McEvoy’s mission to understand the blue lotus started with a journey down a YouTube rabbit hole. About five years ago, in high school, he stumbled across a BBC series called Sacred Weeds that aired in 1998 and was replete with corny tie-dye scene transitions and an ethically shady study protocol.

In the episode, anthropologists recruited two volunteers to a sprawling manor in the English countryside. The scholars provided them with a goblet of lily-steeped wine and mused about the risk and thrill of conducting what they claimed was the first test of the famed flower’s psychedelic properties.

“We had gathered to investigate an ancient mystery,” the narrator said, with grandiosity fit for cringe-worthy ‘90s documentary TV. “Is the blue water lily a lost drug plant once beloved by the ancient Egyptians? Could it be that today our two volunteers might step through a doorway and see the world as it might once have been seen in the time of the pharaoh?”

The cameras roll as the volunteers imbibe. Within minutes, they become giggly, don coats and frolic in the rain and through the woods, wondering aloud whether they are under the influence. Meanwhile, the researchers watch from a window and debate whether the participants are high. Ultimately, they decide that they are.

McEvoy couldn’t stop thinking about the show and the flower. He was fascinated by the plant’s lore and a simple question: Were the flowers used in the show the same type of lily as the one used in ancient Egypt, distinct for its spotted sepals and consistent number of petals?

Liam McEvoy has also examined artifacts at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at UC Berkeley. The museum houses an enormous collection of artifacts from ancient Egypt.

As he did more research, he learned of the Egyptian blue lotus’s prominence through classes and ancient artifacts kept at Berkeley’s own Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. As he learned to read hieroglyphs, he came to understand the flower’s importance on ancient scrolls and its role in the Hathoric Festival of Drunkenness, in which ancient people got drunk, passed out and — for a fleeting moment when they awoke — reportedly saw the face of Hathor, the goddess of love, beauty and fertility.

“It’s always depicted with the same petal shape,” McEvoy said. “It’s always depicted with the spots on the bottom of sepals. It’s a very specific plant.”

As his research questions took shape, he wanted to know if the plants used in ancient Egypt were the same as those purportedly available online. He also wanted to see how different processing methods affected the release of the psychoactive alkaloid nuciferine that causes the euphoria.

Step one was to find a plant. That authentic Egyptian blue lotus has become incredibly rare, with the construction of the Aswan dam on the southern Nile dramatically altering its native environment. The plant is now considered to be threatened and on the verge of being endangered. While the UC Botanical Garden has a vast array of plants for scholars to study, the Egyptian blue lotus was not among them. And other botanical gardens around the world were unable to provide samples for his research, McEvoy said.

So he did what any young researcher might do: He resorted to Reddit.

On a page devoted to the blue lily, he contacted someone in Arizona who claimed to have authentic Nymphaea caerulea. The user was intrigued by McEvoy’s study and overnighted him a living plant that botanists confirmed was legitimate. During its blooming season last summer, he collected its flowers for analysis. It now lives in the recently reopened Virginia Haldan Tropical House at the UC Botanical Garden; McEvoy believes it’s the only university botanical garden in the country with a living Egyptian blue lotus.

He also ordered dried petals of the supposed lotus on Etsy.

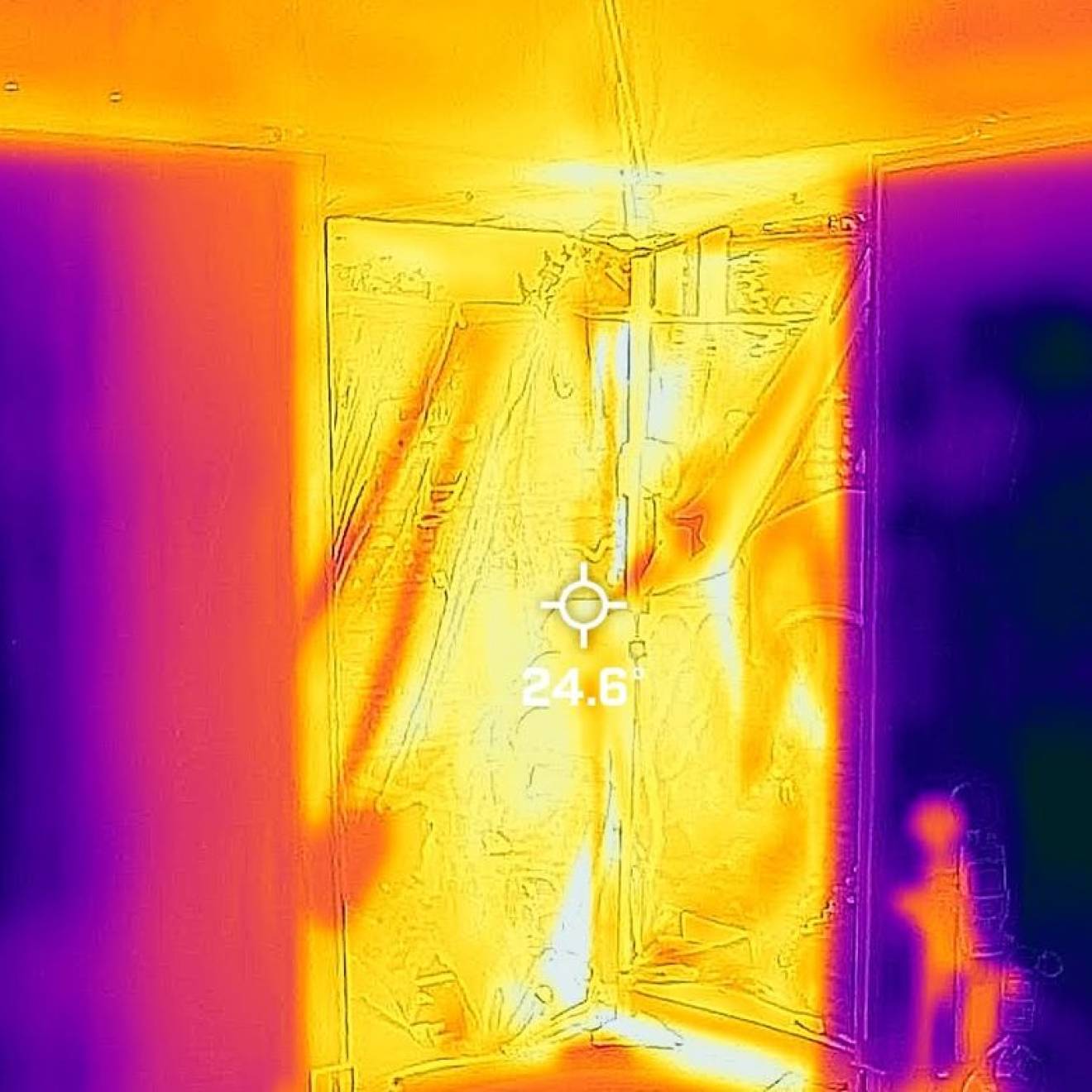

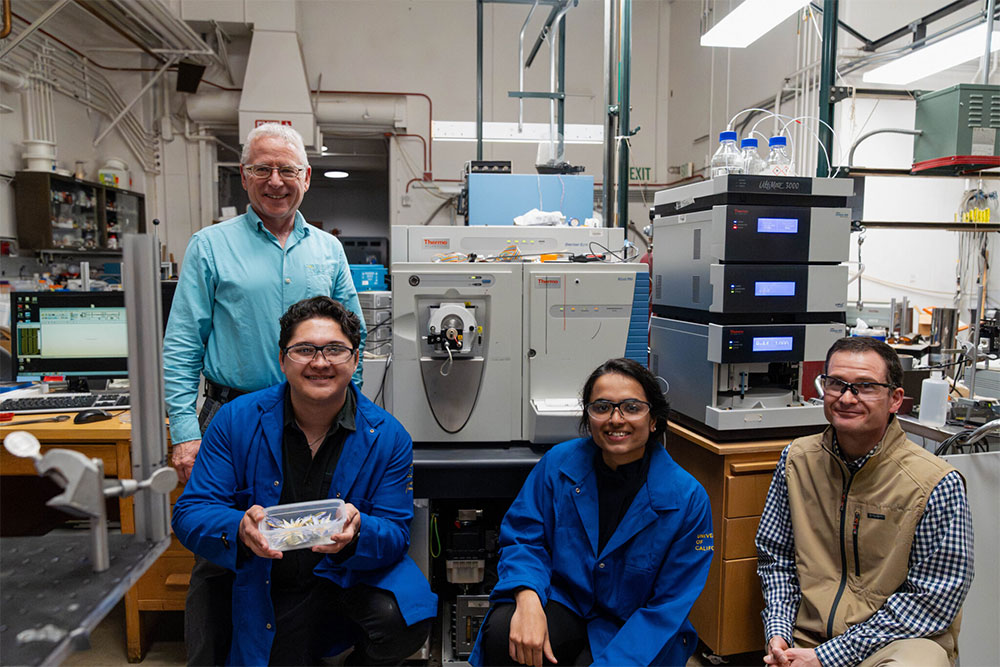

With the help of Evan Williams, a Berkeley professor of chemistry, and Anthony Iavarone, a project scientist, McEvoy used mass spectrometry to get a general idea of the chemical composition of both samples.

They found the nuciferine levels were much higher in verified Egyptian blue lotus when compared to the Etsy-sourced flower, leading McEvoy to believe that flowers sold online are actually a visually striking, but otherwise common, non-psychoactive water lily.

“I said, ‘I knew it!'” McEvoy recalled.

An online search for the Egyptian blue lotus turns up dozens of sellers offering all manner of options purporting to be the real deal. A $20 bag of petals that promises to “promote sleep” and “boost immunity.” A $90 bag of petals that can cause “heightened awareness and spiritual connection.” A $154 bottle of essential oil that “may boost sexual health and desire.”

“The stuff being sold online is not the same, and our findings suggest the blue lotus is actually unique in comparison to other water lilies,” McEvoy said. “It’s a very specific plant.”

“The stuff being sold online is not the same, and our findings suggest the blue lotus is actually unique in comparison to other water lilies,” Liam McEvoy said.

Next, McEvoy wanted to know if the authentic plant’s psychedelic elements could be extracted by a soak in red wine. Pure and chemically isolated nuciferine, an alkaloid, is easily dissolved in alcohol, he said. But not a nuciferine-packed flower with a waxy, water-repellent exterior.

Instead, it needed something else to unlock its nuciferine: a substance akin to olive oil, with fats that allowed the slightly fat-soluble alkaloid to fully dissolve in wine.

“We’re beginning to think the ancient Egyptians didn’t just put it into wine,” McEvoy said. “We hypothesize they actually created an infused oil, which was later added into wine.”

McEvoy’s findings add new depth to prevailing understandings about ancient Egypt and about questionable lotus-laced supplements sold online today. In ancient times, the ceremonial beverage du jour may have been a potion of oil and wine steeped with lotus flowers. Today, the promises of what’s marketed online as a miracle wellness elixir appear to be too good to be true.

McEvoy will graduate this fall to pursue a career in intellectual property law. Using his work translating trade secrets encoded in ancient myth, he wants to reconstruct how our ancestors lived thousands of years ago.

“There should be someone at the table who has studied people — not just economics, money or political science,” McEvoy said. “Someone who sees people as human beings and sees communities as interconnected webs of meaning.”But before he begins that work, he wants to finish his experiments.

In the coming months, McEvoy, Williams and Veena Avadhani, a Ph.D. candidate in chemistry, plan to use intense pressure to tear apart the flower samples at the chemical level. That process, called liquid chromatography, will separate the complex mixture of compounds into their individual chemical components. Once they rerun the mass spectrometry analysis, they will have applied one of the gold standard tests of analytical chemistry to the plant at the center of those dubious online health claims.

McEvoy also wants to return to the Hearst Museum’s enormous collection of Egyptian artifacts, where he plans to conduct one more round of chemical testing on a 3,000-year-old goblet. Such a test could reveal whether there are any traces of fat molecules from an oil, which could bolster his idea that it wasn’t just wine steeped with lotus flowers during the ancient rituals.

Perhaps there would even be trace amounts of the plants themselves — a discovery that would add a new chapter to the flower’s story and its psychedelic properties.

Together, McEvoy sees his work as “a rare example of how ancient magic and modern science can come together to deepen our understanding of the nature that has always surrounded us.”