Edward Lempinen, UC Berkeley

Millions of U.S. students are returning to K-12 classrooms, and after the profound disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, many of their parents, teachers and principals are worried about the learning lost while students attended classes remotely.

It stands to reason: In the 17 months since the pandemic forced school shutdowns across the nation and much of the world, students have faced challenges unknown in modern times. They’ve been stuck at home, taking classes via the dull gleam of their computer screens, with little or no access to typical academic and social activities.

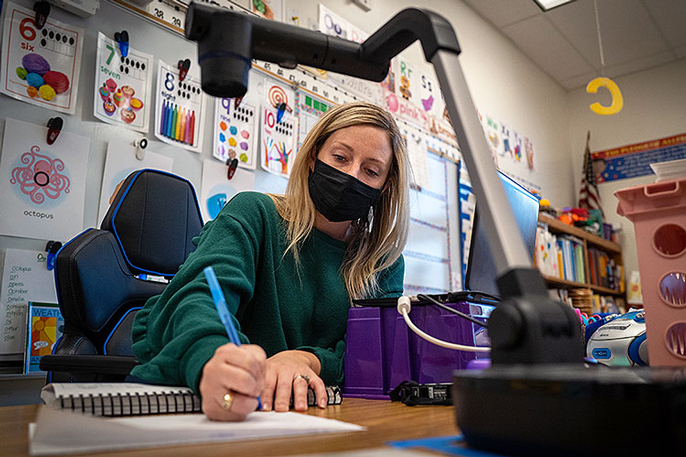

Credit: Julia Perry

But while some evidence suggests the pandemic has slowed students’ academic progress, UC Berkeley education scholars caution that educators shouldn’t obsess about it. Better, they said, to focus more on the social and emotional well-being of students — and their teachers — as in-person classes resume after a historic period of uncertainty, fear and loss.

“The idea that what schools offered during the pandemic has been universally substandard … is deeply flawed,” said Janelle Scott, a scholar in education policy based at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Education (GSE). “If we care about the whole child, the whole student, the whole young adult who’s in high school, then we really want to tackle these other issues if we want to make up for the difficulty of the 2020 school year.”

“We absolutely want children to learn to read and write,” added Travis Bristol, whose research at GSE focuses on teacher education and education policy. “That’s just fundamental to being a participant in this democracy. … But what we’ve seen with the pandemic is that children and teachers are in so much pain and fear and sadness — and you can’t create conditions for children to learn if they don’t feel safe.”

Credit: Dara Tom

While educational progress may have been slowed by the pandemic, the UC Berkeley scholars offered a perspective both more holistic and more nuanced. Students — especially low-income students and students of color — may have struggled with their parents’ financial insecurity and job losses, and the illness or death of family members. And teachers were plunged literally overnight into the peculiar demands of teaching online, without training, and deprived of the emotional connections to students that support learning.

Now, the UC Berkeley scholars say, as schools push for recovery amid a still-threatening health climate, students will depend on their teachers for both academic support and emotional security. And to be most effective, teachers will in turn need special support from administrators and policymakers.

But they pointed to innovations in California and other states, and said that if others follow, changes implemented starting this fall may lead to long-term improvements with broad benefit for schools and communities.

Short-term learning loss can distract from long-term challenges

A number of research reports have identified and quantified the learning loss associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, and those have been amplified by extensive news coverage.

One paper found that student progress essentially stopped while they were learning from home; a separate report found students fell behind by several months in math and reading, with the learning losses potentially permanent — and worse for students of color.

Credit: Phil Roeder/Flickr

But the UC Berkeley scholars raised sharp questions about the importance of such findings.

“What does it actually mean to lose a month of learning?” Scott asked. “Do you mean that you lost memory of some facts? OK, it seems like that would be pretty easy to make up with adequate interventions. Are you saying that the students have lost something that can’t be recovered? That’s kind of a dangerous claim and, from my perspective, it’s not well-grounded in a robust understanding of cognition.”

But the scholars cited another, less quantifiable risk: failing to recognize the extraordinary effort made by students and teachers in extremely difficult circumstances.

Credit: UC Berkeley

“I do think, academically, the pace of learning among many students has been disrupted during the pandemic,” said GSE scholar Chunyan Yang. “But a lot of times, when we talk about learning loss with teachers, it triggers a lot of questioning and resistance. Teachers feel that they have been making so much effort during the pandemic. They’ve imposed on their family’s time and neglected their own mental health to try to minimize the loss among their students. They say it is demoralizing to work that hard without any recognition.”

So too with students, Scott said. “When we talk about learning loss, students are listening,” she said. “Talking about them as permanently damaged learners? I think we need to convey some respect for what they have endured, what they have learned, and how they have developed despite the immense challenges of the last 18 months.”

Now, as students return to in-person classes, Scott sees the risk that a focus on learning loss without the broader context will lead administrators and policymakers to back questionable strategies such as intensive remedial classes, tracking students into different classes based on perceived ability, extending the school year or increasing standardized testing.

Using those approaches may seem to punish both students and their teachers. And if they don’t account for the social and economic context that define day-to-day life for many students, they may have limited benefit.

Learning loss often signals a larger trauma

By now it is well-established that the impact of the pandemic has fallen disproportionately on low-income people and on Black, Latinx and Indigenous people. They are less likely to work from home, and less able to find child-care. They have lost jobs at higher rates, fallen behind on rent at higher rates, and have gotten sick and died at higher rates.

On matters of education, however, Bristol and others argue that people of color are struggling with a “dual pandemic”: Systemic racism funnels Black and Latinx students — and teachers — into schools that have greater challenges resulting from poverty, but fewer resources to address the needs. Low-income students are less likely to have wireless connections to the internet, and less likely to have computers. Their parents may be working outside the home, leaving children to take care of themselves.

In that view, the pandemic of COVID-19 only compounds the underlying pandemic of racism and poverty.

Credit: iStock/twinsterphoto

Asian American students, meanwhile, face a unique challenge: They are often stigmatized or bullied by other kids who blame China for the COVID-19 virus. One 2020 report, conducted by students and issued through the Stop AAPI Hate Youth Campaign, found that one in four Asian American young people had experienced racism in the past year, much of it linked to the pandemic.

Yang has extensively studied bullying of Asian American and other young people in the period before COVID-19, and says these experiences have continued to have a detrimental impact during the pandemic.

“A lot of students, when they think about going back, start thinking about what they have experienced at school before,” she said. “They might be feeling disconnected or unsafe in school. Many Asian and Asian American parents are also afraid of sending their children back to school in person because of the anti-Asian violence they have been experiencing or witnessing since the pandemic began.”

During the pandemic, teachers have had to interact with students and their families in new ways, and through Zoom classes they literally see into the child’s home life. Scott says they know that learning loss doesn’t begin to explain the insecurity and trauma experienced by many students.

“They’ve seen students who have lost one or both parents to COVID and other catastrophic illness, students who live in multigenerational family situations where they’ve lost multiple family members,” she said. Learning loss doesn’t get at the deep fear when you have a family member who’s sick, or how difficult it is to focus on school when someone is sick and you’re being quarantined.”

Teaching in a pandemic: ultra-committed and overextended

Credit: Phil Roeder/Flickr

In her interviews with teachers, Yang has found that many feel stressed and overwhelmed by the demands of online teaching and taking care of their students and families who are suffering. “Compassion fatigue” sets in, and complaints of learning loss by analysts far from the classroom add to their despair.

“Although teaching is always a stressful occupation,” one teacher told Yang in a recent research interview, “it is one where face-to-face time and small moments of success allow a teacher to re-energize. Now I no longer go home and problem-solve and figure out the puzzle of the day. I close my laptop and feel like an absolute failure.“

Another teacher was troubled by the realization that students’ families were struggling with childcare, internet access and job insecurity. “There have been so many nights where I think about my students and cry myself to sleep,” the teacher said. “It has made me realize that school is about so much more than teaching academics.”

For the Berkeley scholars, the conclusion is clear: For schools that are reopening now, teachers need support just as much as students.

“You can’t bring students back until you bring teachers back,” Bristol said. “Teachers have had these extraordinarily challenging experiences, and they’re dealing with their own social and emotional challenges. Schools need to support them. … They need to provide space for them to talk about what it’s been like to experience teaching in this pandemic, or in these twin pandemics.”

The pandemic could drive historic changes in schooling

Across the nation, educators are working to innovate in a way that makes students, teachers and schools more resilient. For example, Bristol said, some are using funds from the federal American Rescue Plan to improve access to broadband internet connections and learning technology. That has value not just with a new wave of COVID-19, he said, but also when climate-related disruptions force schools to close.

An immediate focus is likely to be on mental health support for school communities. As in-person classes resume, Bristol said, “we’ll see a lot more focus on the social and emotional side, and less on the academic side, even in the preparation of teachers.”

Credit: Blain Watson

Yang agreed, saying that many school districts are now developing stronger systems for identifying students with mental health risks and providing social and emotional support for faculty and staff.

But mental well-being is inevitably linked to a school’s academic program, and Scott said schools should work to offer students learning that is rigorous, but also “really enriching and dynamic … so that students look forward to learning.”

That would include studies of race relations and civil rights, linked to the interwoven crises that flowed from the pandemic and the police murder of George Floyd in 2020.

“Our students are quite hungry for that,” Scott said.

While some U.S. communities are fighting about whether returning students should be required to wear masks or be vaccinated, the UC Berkeley scholars see encouraging signals that others are imagining a new role for schools.

Last summer in Oakland, California, schools became food distribution sites for city residents in need. And under a law signed by California Gov. Gavin Newsom, schools statewide will provide lunches to all students, regardless of family income.

Bristol said such policies reflect a movement toward “community schools” that provide a range of services to support students, and especially those from low-income families — not just food, but education technology, health services or even just a quiet place to study.

Underlying such innovations is a core assumption about the importance of education. “Children are brilliant and resilient,” Scott said, “and that transcends poverty and race and immigration status. We respect them. We know that they are able to learn — and learn at very advanced levels — provided we give them the supports they need.”