Sonia Fernandez, UC Santa Barbara

Alma Cortez-Lara immigrated to the United States from Mexico when she was very young, and lived the life of the child of migrant workers. She lived in poor neighborhoods and learned English, serving as the translator for her Spanish-speaking parents, who spent their days in the fields.

As she got older, she never fell into the trap of drugs or early pregnancy, as many of her contemporaries did. In fact, she eventually graduated from college and is now a teacher in her old community in Napa, Calif.

Amílcar Ramírez is a moreno — dark-skinned — Latino, and throughout his youth had to navigate a society that treated him according to whether he seemed “black” or “brown.” A lot of times the situation was no big deal, but occasionally in the Los Angeles community his family moved to from their native Honduras, there would be interracial tensions. Fortunately, through the wisdom of his parents, he didn’t get caught up in any of it, and his multiculturality eventually served him, as he got his law degree, which he plans to use to practice immigration law.

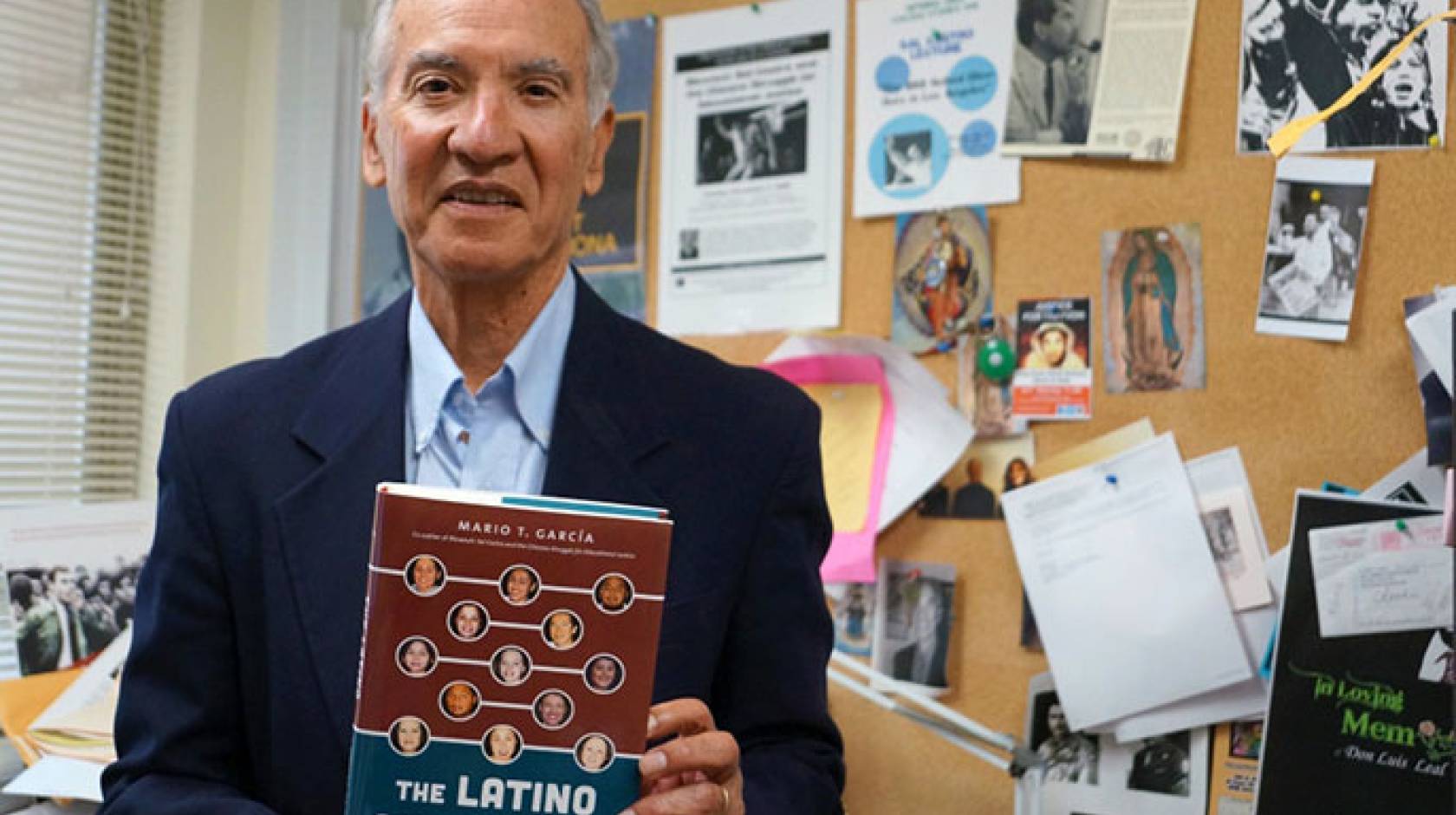

What sets Cortez-Lara and Ramírez apart from the seemingly thousands of Latino immigrants, or children of immigrants who become stereotyped into gangsters, drug dealers and unwed young mothers? What do these people have in common? These are the kinds of questions UC Santa Barbara professor of Chicano studies Mario T. García seeks to answer in his recently published book “The Latino Generation: Voices of the New America” (University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

“The Latino Generation involves not only Mexican-Americans but also other Latinos, like Central Americans and others who come of age in the 1980s and ’90s,” said García, who studies Chicano history from a generational standpoint. His other studies have examined Mexicans in the United States who were the result of the U.S.–Mexico War of the 1840s, which he calls the “Conquered Generation,” and the massive influx of immigrants from south of the new border in the following generation that he calls the “Immigrant Generation.” The group that follows is called the “Mexican-American Generation,” which consisted of a mix of new immigrants and second-generation Mexicans in the U.S., who felt the effects of the Great Depression and World War II. The 1960s and ’70s brought the Civil Rights Era and the “Chicano Generation.”

“Demographically, the members of the Latino Generation are children of immigrants who have come in the later ’60s and the ’70s. But also, they are the children of Central American refugees who started coming in the ’80s,” said García. They are bound by other factors, including globalization and the U.S.’s need for laborers in the service industry.

This generation is also unique in that Latinos now represent the largest minority in the U.S., and with that growth comes the social and political sway that accompanies large markets and voting blocs, García said.

With that power also comes responsibility, he added, a responsibility that requires young Latinos to raise the bar on themselves and each other, and for the community at large to recognize their potential.

“If we’re staring into the face of the future, demographically, where are we going to fill our technical needs, our expertise needs in high tech and the professions if it doesn’t come from this growing population?” asked García. Dropout rates remain high in secondary schools, and the effects of segregation and racial discrimination are still apparent as far as education in the Latino community.

For this reason, he offers these stories not as a social science survey, but as “testimonios” — a new narrative to combat the kind of stereotypes into which Latinos are often confined: the poorly-educated, low-skilled, oftentimes criminal individuals who don’t assimilate into the greater community.

To find these stories, García had to look no further than the UCSB campus; his subjects were all former students of his who quite openly shared their experiences. Over the five years this book was in progress, García winnowed the many stories down to 13, each of which depicts the various circumstances that young Latinos have had to face, and overcome. García’s hope is that these stories can serve as templates on which the members of the emerging Latino generation can model themselves.

“Demographically, Latinos are in many ways the future of this country, and because of that these voices need to be heard,” he said. “And they need to be heard because these are compelling American stories, they are stories of real people with the same kinds of aspirations and dreams as other Americans.”