Satchin Panda and Pam Taub, The Conversation

People with obesity, high blood sugar, high blood pressure or high cholesterol are often advised to eat less and move more, but our new research suggests there is now another simple tool to fight off these diseases: restricting your eating time to a daily 10-hour window.

Studies done in mice and fruit flies suggest that limiting when animals eat to a daily window of 10 hours can prevent, or even reverse, metabolic diseases that affect millions in the U.S.

We are scientists — a cell biologist and a cardiologist — and are exploring the effects of the timing of nutrition on health. Results from flies and mice led us and others to test the idea of time-restricted eating in healthy people. Studies lasting more than a year showed that TRE was safe among healthy individuals. Next, we tested time-restricted eating in patients with conditions known collectively as metabolic syndrome. We were curious to see if this approach, which had a profound impact on obese and diabetic lab rats, can help millions of patients who suffer from early signs of diabetes, high blood pressure and unhealthy blood cholesterol.

A leap from prevention to treatment

It’s not easy to count calories or figure out how much fat, carbohydrates and protein are in every meal. That’s why using TRE provides a new strategy for fighting obesity and metabolic diseases that affect millions of people worldwide. Several studies had suggested that TRE is a lifestyle choice that healthy people can adopt and that can reduce their risk for future metabolic diseases.

However, TRE is rarely tested on people already diagnosed with metabolic diseases. Furthermore, the vast majority of patients with metabolic diseases are often on medication, and it was not clear whether it was safe for these patients to go through daily fasting of more than 12 hours — as many experiments require — or whether TRE will offer any benefits in addition to those from their medications.

In a unique collaboration between our basic science and clinical science laboratories, we tested whether restricting eating to a 10-hour window improved the health of people with metabolic syndrome who were also taking medications that lower blood pressure and cholesterol to manage their disease.

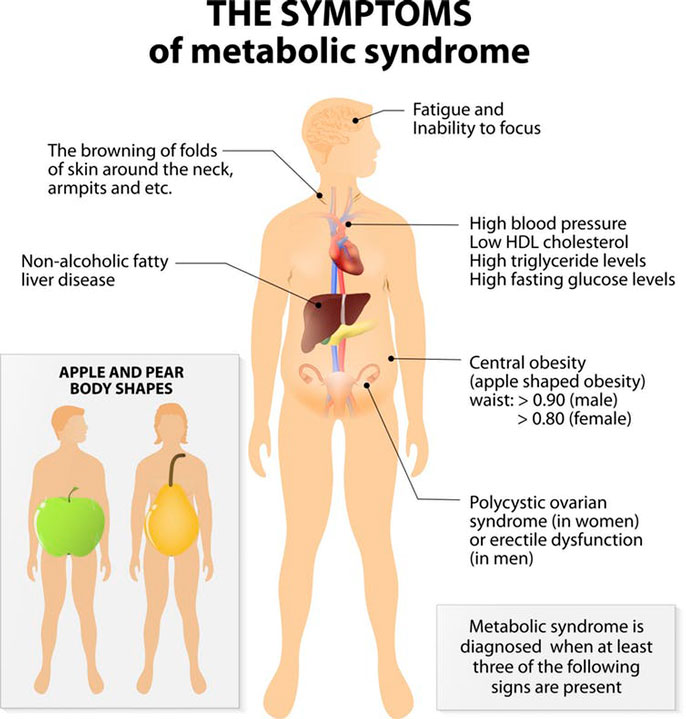

We recruited patients from UC San Diego clinics who met at least three out of five criteria for metabolic syndrome: obesity, high blood sugar, high blood pressure, high level of bad cholesterol and low level of good cholesterol. The patients used a research app called myCircadianClock, developed in our lab, to log every calorie they consumed for two weeks. This helped us to find patients who were more likely to spread their eating out over the span of 14 hours or more and might benefit from 10-hour TRE.

We monitored their physical activity and sleep using a watch worn on the wrist. As some patients with bad blood glucose control may experience low blood glucose at night, we also placed a continuous glucose monitor on their arm to measure blood glucose every few minutes for two weeks.

Nineteen patients qualified for the study. Most of them had already tried standard lifestyle interventions of reducing calories and doing more physical activity. As part of this study, the only change they had to follow was to self-select a window of 10 hours that best suited their work-family life to eat and drink all of their calories, say from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. Drinking water and taking medications outside this window were allowed. For the next 12 weeks they used the myCircadianClock app, and for the last two weeks of the study they also had the continuous glucose monitor and activity monitor.

Credit: Designua/Shuttersock.com

Timing is the medicine

After 12 weeks, the volunteers returned to the clinic for a thorough medical examination and blood tests. We compared their final results with those from their initial visit. The results, which we published in Cell Metabolism, were pleasantly surprising. We found most of them lost a modest amount of body weight, particularly fat from their abdominal region. Those who had high blood glucose levels when fasting also reduced these blood sugar levels. Similarly, most patients further reduced their blood pressure and LDL cholesterol. All of these benefits happened without any change in physical activity.

Reducing the time window of eating also had several inadvertent benefits. On average, patients reduced their daily caloric intake by a modest 8 percent. However, statistical analyses did not find strong association between calorie reduction and health improvement. Similar benefits of TRE on blood pressure and blood glucose control were also found among healthy adults who did not change caloric intake.

Nearly two-thirds of patients also reported restful sleep at night and less hunger at bedtime — similar to what was reported in other TRE studies on relatively healthier cohorts. While restricting all eating to just a six-hour window was hard for participants and caused several adverse effects, patients reported they could easily adapt to eating within a 10-hour span. Although it was not necessary after completion of the study, nearly 70 percent of our patients continued with the TRE for at least a year. As their health improved, many of them reported having reduced their medication or stopped some medication.

Despite the success of this study, time-restricted eating is not currently a standard recommendation from doctors to their patients who have metabolic syndrome. This study was a small feasibility study; more rigorous randomized control trials and multiple location trials are necessary next steps. Toward that goal, we have started a larger study on metabolic syndrome patients.

Although we did not see any of our patients go through dangerously low levels of glucose during overnight fasting, it is important that time-restricted eating be practiced under medical supervision. As TRE can improve metabolic regulation, it is also necessary that a physician pays close attention to the health of the patient and adjusts medications accordingly.

We are cautiously hopeful that time-restricted eating can be a simple, yet powerful approach to treating people with metabolic diseases.

This article was written by Satchin Panda, professor of regulatory biology at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, adjunct professor of Cell and Developmental Biology at the University of California, San Diego and Pam Taub, associate professor of medicine, at the University of California, San Diego. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Top image via ratmaner/Shutterstock.com.