Stuart Wolpert, UCLA

UCLA biochemists have devised a clever way to make a variety of useful chemical compounds, which could lead to the production of biofuels and new pharmaceuticals.

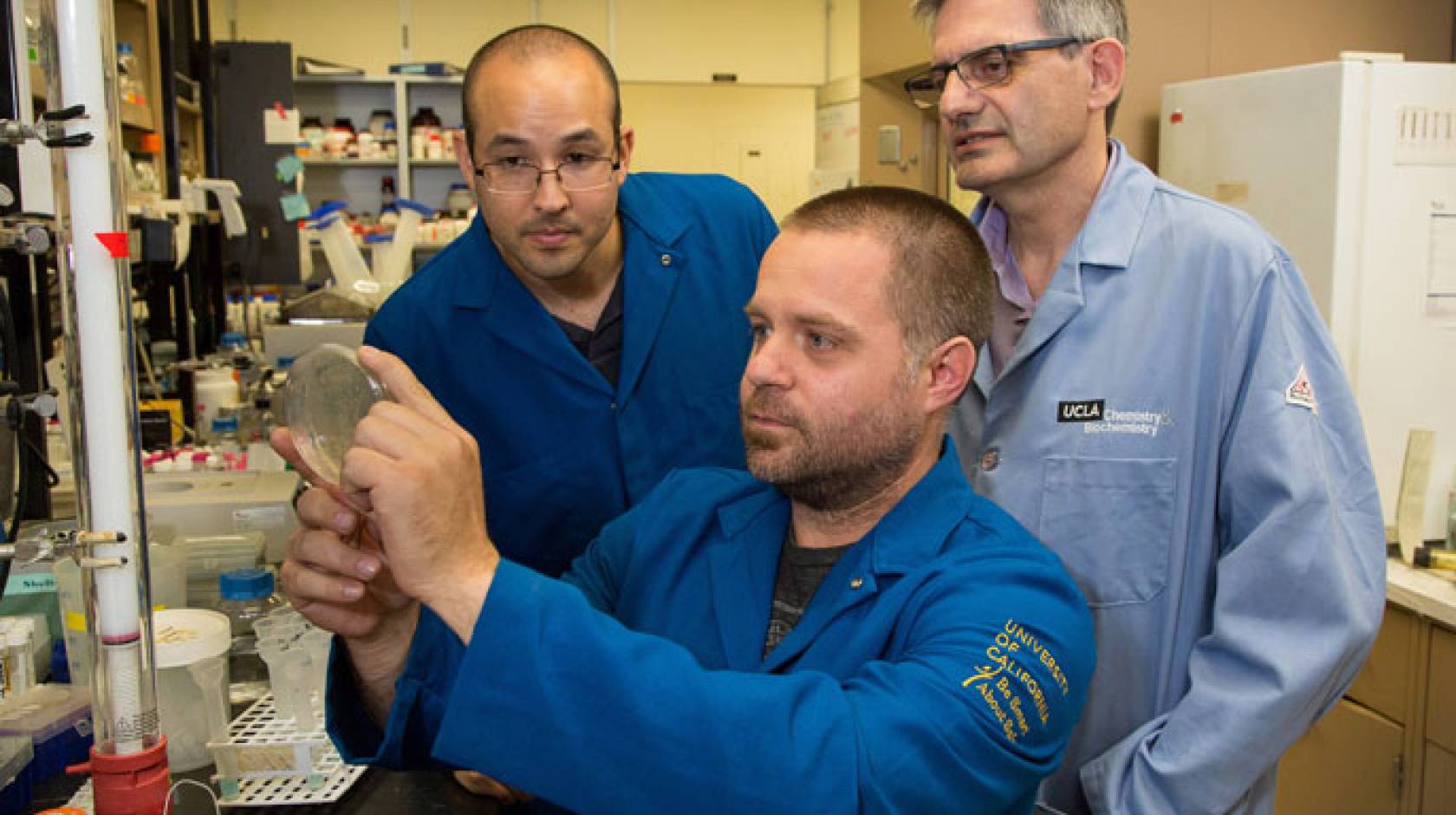

“The idea of synthetic biology is to redesign cells so they will take sugar and run it through a series of chemical steps to convert it into to a biofuel or a commodity chemical or a pharmaceutical,” said James Bowie, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry in the UCLA College, and senior author of the new research. “However, that’s extremely difficult to do. The cell protests. It will take the sugar and do other things with it that you don’t want, like build cell walls, proteins and RNA molecules. The cell fights us the whole way.”

As an alternative, Bowie and his research team have developed a promising approach he calls synthetic biochemistry that bypasses the need for cells.

“We want to do a particular set of chemical transformations — that’s all we want — so we decided to throw away the cells and just build the biochemical steps in a flask,” Bowie said. “We eliminate the annoying cell altogether.”

The biochemists purified more than two dozen enzymes in particular combinations and concentrations, put them in a flask and added glucose. The enzymes and pathways, created in Bowie’s laboratory, are not necessarily found in nature. “When we don’t have to worry about keeping cells happy, it’s easier to rearrange things the way we want,” he said.

“If the enzymes are not good enough — not fast enough, not stable enough — then we re-engineer them,” said Tyler Korman, a postdoctoral scholar in Bowie’s laboratory and co-author of the study.

Synthetic biochemistry holds potential for many products

The research, published today in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, demonstrates that the biochemists can generate complex enzyme systems outside the cell that function well enough to be useful for the production of biofuels and commodity chemicals.

Synthetic biochemistry could be used for many industrial products, including producing plastics, flavors and scents, and perhaps eventually biofuels, said Bowie, a member of the UCLA–Department of Energy Institute’s Division of Systems Biology and Design and UCLA’s Molecular Biology Institute.

To convert glucose into a biofuel, bioengineers would ideally want cells to convert 100 percent of the sugar into fuel. Ethanol can be produced by yeast fermentation in about a 70 percent yield, by the same process we use to make beer and wine, “but that’s after effectively thousands of years of optimization by man to increase alcohol levels in our favorite drinks,” Bowie said. The best yields for cell-produced chemicals in bioengineered strains are generally much lower or have other problems, he said.

Bowie, Korman and Paul Opgenorth, another postdoctoral scholar in the laboratory, report they have achieved approximately a 90 percent yield for the production of a biodegradable plastic.

The research team is working to overcome remaining challenges, including regulating the production of high-energy molecules needed for biochemical reactions.

In an important prelude to the current study, the biochemists reported on June 17, 2013 in the journal Nature Communications a major advance in regulating these high energy molecules — a system they call a molecular purge valve — and are continuing to develop other regulatory “tricks.”

“We have to make synthetic biochemistry robust enough to work in a very large industrial plant,” said Bowie, who has conducted research at UCLA since 1989, first as a postdoctoral scholar, and with his own laboratory since 1993.

They are in the early stages of forming a company, called Invizyne Technologies, Inc., for which Bowie is a scientific adviser.

The research was federally funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (grants DE-FOA-0001002 and DE-FC02-02ER63421).