Emily Cerf, UC Santa Cruz

When UC Santa Cruz postdoctoral scholar Merly Escalona assembled the first-ever reference genome for the Stephen Colbert Trapdoor Spider, she was shocked by the dataset's unexpectedly large size. For a small invertebrate, this California native spider’s genetic code was very fragmented and consisted of about four billion bases (four gigabases) — larger than the human genome’s size of a little more than three gigabases.

There have been lots of other surprising discoveries as Escalona works to assemble 150 different high quality reference genomes, each of which comprises a detailed map of the genetic material of a species, in her role on the scientific team for the California Conservation Genomics Project (CCGP). This $12 million state-funded project aims to create a comprehensive genomic dataset representative of the state’s biodiversity, as outlined by a recent paper in the Journal of Heredity.

The CCGP, launched in 2019, is led by director Brad Shaffer at UCLA and involves researchers from the University of California, California State Universities, and officials from state and federal regulatory agencies and non-governmental organizations. The leadership has been consistently working with state officials to make sure the results can be an invaluable and lasting resource for shaping conservation policy.

“We are generating very high quality data that will be a lasting resource for this project and will form a foundation for future conservation actions,” Shaffer said.

Collaborating for conservation

Escalona is just one of 15 researchers at UC Santa Cruz working on the project. She is on the leadership team alongside faculty such as professor of ecology and evolutionary biology Beth Shapiro, who is on both the Scientific Executive Committee and the Technical Committee for the project, and associate professor of biomolecular engineering at the Baskin School of Engineering Russell Corbett Detig, who is the project’s bioinformatics lead. Both researchers are also on the leadership team at the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute.

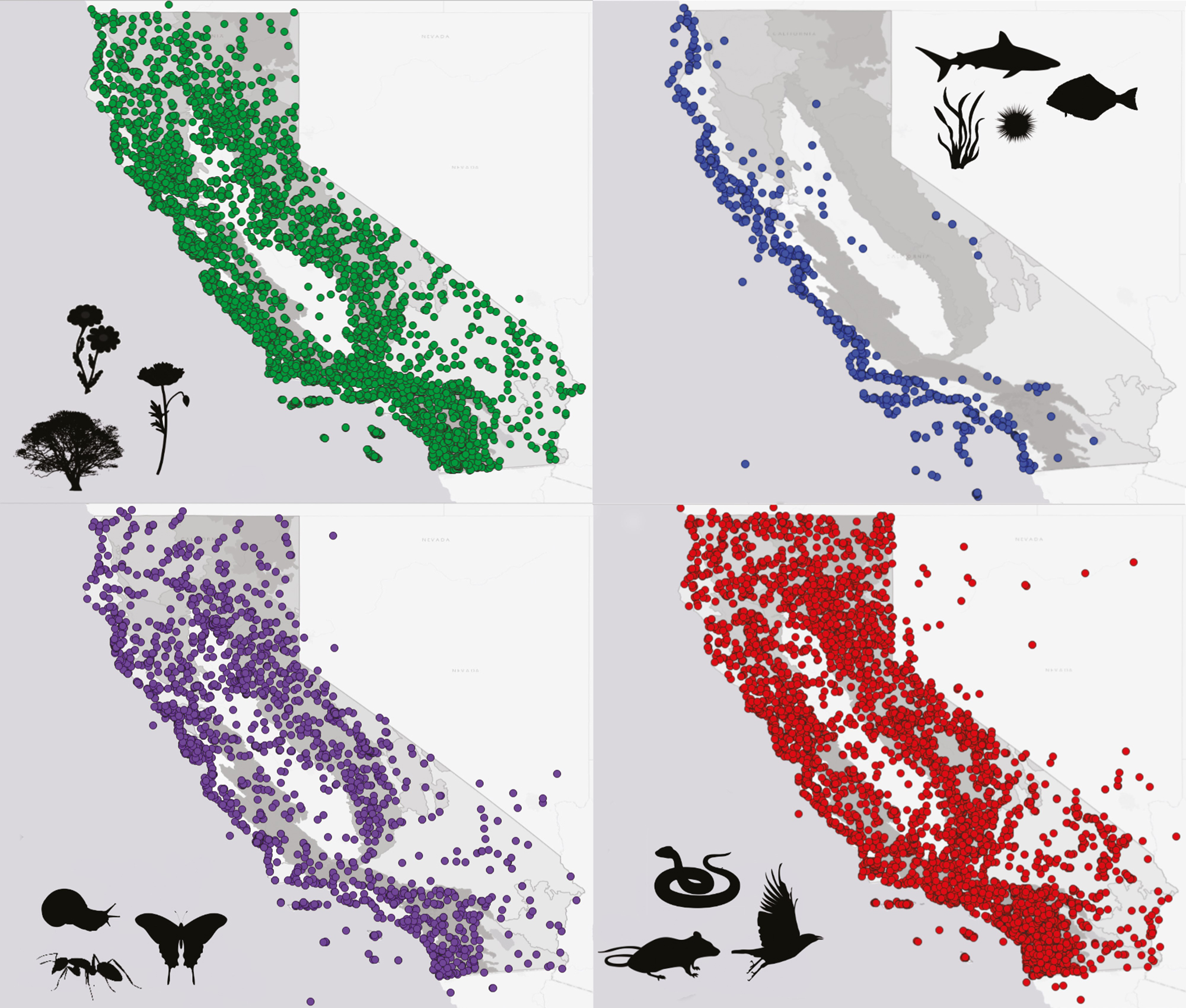

The project is the first of its kind in terms of scale in the field of conservation genomics. Researchers are studying a range of species to get an idea of the genetic biodiversity that exists across the state, from the mountain lions and the deer they hunt amidst the redwoods to the surfgrasses that sway in tide pools along the coast.

“The north to the south of California spans all sorts of ecosystem diversity in a way that is unique to the state,” Shapiro said. “There aren’t many contiguous governed bodies that span this much ecological diversity. This is really an opportunity to capture how ecological diversity is partitioned across so many different ecosystems.”

This work was presented with significant challenges by the surge in natural disasters affecting the world in recent years. Wildfires and droughts in the state spurred by climate change made it difficult to access some plant samples necessary to assemble genomic data. The pandemic slowed lab and field work and extended the timeline of the CCGP from three to four years.

Despite these setbacks, the CCGP is continuing with its data collection phase, which includes both reference genomes and resequencing many individuals of each species. The reference genome phase of the project is nearing completion, with virtually all tissues in hand, most in the data acquisition and analysis pipelines, nearly a third fully assembled, and about a quarter already available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s open source library of genomic data. The process of resequencing, generating data from more than 100 individuals from each species under study, is now well underway and moving into high gear.

Escalona’s reference genomes will serve as a point of comparison to study genetic diversity within a species. In addition, the CCGP will resequence 100-150 additional genomes for each species, which they will study by comparison to the high-quality reference genome. By mapping the variations that occur in these genomes, researchers will discover how much genetic diversity exists in each species and how this diversity is distributed geographically throughout the state.

This information will be used to identify which natural habitats should be prioritized for protection and create a snapshot in time of genomic biodiversity in the state as it exists now, an important reference point as the natural world is impacted by climate change.

In generating both reference genomes and the resequenced genomes, the CCGP project is considerably larger in scale than other projects in conservation genomics. Data sets of this size are scarcely seen outside of human genomics, where biomedical funding can back such computationally intensive projects. In the end, between reference genomes and resequencing, about 22,000 genomes will be sequenced, a feat that speaks to both the recent advancements in genomics technology and the dedication of the researchers involved.

UC Santa Cruz contributions

Principal investigators will use the genomic data to study each individual species from the project to understand these creatures, many of which are unique to California. For example, assistant adjunct professor of ecology and evolutionary biology Rachel Meyers is leading research into endangered vernal pool grasses, while associate professor of biomolecular engineering Christopher Vollmers is fittingly studying banana slugs.

But the study of these native species may open more questions than it answers. As Escalona works in the UC Santa Cruz Paleogenomics Lab led by professors Shapiro and Richard (Ed) Green, she says she is constantly surprised by the genomic mysteries that exist in California’s nature, such as the huge size of the trapdoor spider’s genome, or how relatively easy it was to assemble the black bear’s genome.

“It kind of just blows your mind how different [the genomes of species] can be, even closely related species,” Escalona said. “Having these reference genomes is a big resource for us to give to the community.”

The comparison of the geographic distribution of biodiversity across the state will be made possible by the bioinformatics data analysis and processing taken on by Corbett-Detig as well as UC Santa Cruz bioinformatics postdoc Erik Enbody and data wrangler Cade Mirchandani. Corbett-Detig’s group is working to make sure that the data from all 150 resequenced genomes within a species are standardized and uniform to make them as comparable as possible.

As this bioinformatics team works on variant calling, the process of comparing the reference genome to the resequenced data to see where the genetic material varies, the massive size of the data presents the most significant challenges, Corbett-Detig noted.

“It's uncommonly large,” he said. “Especially for conservation genomics, it’s a vast dataset with incredible potential.”

Future impact

Once all of the genomic data has been collected, assembled, and made uniform, analyses and landscape genomics work will begin. Led by UC Berkeley associate professor Ian Wang and postdoctoral researcher Anne Changers, the researchers will map out habitat areas that are shown to be particularly vulnerable, in order to better protect them through conservation policy, and identify which populations are the most resilient based on their genetic variation. All of the results will be made publicly available, and the team will work with stakeholders including state and federal regulatory agencies and nonprofits to develop habitat management policy recommendations.

The researchers hope the CCGP can serve as a model to other regions that might want to take on their own studies of genetic biodiversity. California is well-positioned to lead this charge due to both the range of wildlife it is home to and the environmental ethic of its people.

They also want this research to be a springboard for a sustained effort to understand biodiversity in the state, with more work done to understand the success of future interventions that come from this project. But for now, they are happy with the progress being made.

“The quality of the work that's coming out is astonishing,” Shaffer said. “We really are creating a resource that is not going to be thrown in the trash in the next two years when the next technique comes along. That’s a cool place to be as I reflect on a long career of doing this work.”