Edwin Garcia, UC Davis

When Mark Henderson became admissions dean at the UC Davis School of Medicine in 2007, he was charged with making systematic changes to the way students were being admitted to the school.

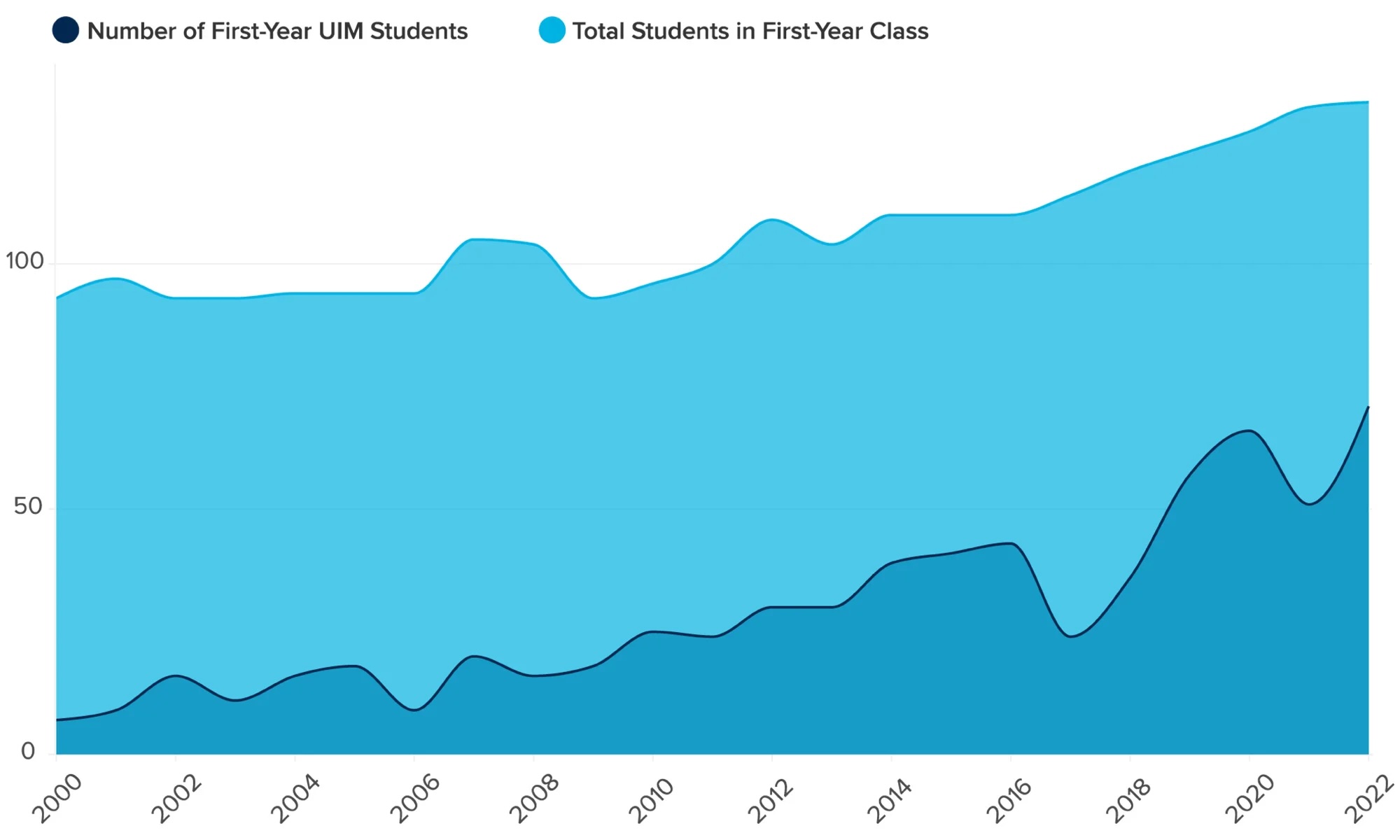

California’s physician workforce wasn’t keeping up with the state’s changing demographics — across social, socioeconomic, or racial and ethnic backgrounds. School enrollment, an obvious indicator of the future workforce, showed that only 10% of UC Davis’ newest medical students were African American, Latino or Native American — in a state that was already majority-minority.

“I knew we had to do a better job of recruiting classes more representative of California’s diverse population and communities,” Henderson recalled.

Seventeen years later, UC Davis is ranked the third-most diverse medical school in the country, according to U.S. News & World Report. Nearly half of UC Davis medical students now belong to groups historically underrepresented in medicine.

UC Davis School of Medicine Demographics 2000-2022

While the U.S. Supreme Court banned race-conscious college admissions last summer, the UC Davis School of Medicine for years has enrolled a student body that better reflects California's diversity in accordance with the ruling and with the state’s own ban on Affirmative Action.

As a school that graduates over 100 doctors a year — more than 80% of whom remain in California — UC Davis plays a key role in addressing the state’s shortage of physicians in rural and lower-income communities. By graduating doctors to meet the needs of the state’s diverse patient population, UC Davis is better fulfilling its mission as a public university in and for California. Studies have shown that patients from minority communities experience better outcomes, including reduced health care expenditures and improved communication, when treated by a provider from their own cultural or linguistic background.

“UC Davis is a great model for how to create an intentional, mission-oriented, holistic approach to admissions,” said Amy Addams, director of student affairs alignment and holistic review at the Association of American Medical Colleges, or AAMC. “They have a very clear sense of who they are as an institution, what their mission is and what they’re trying to accomplish.”

The long journey that increased the UC Davis School of Medicine’s diversity was multifaceted: recruiting students from underserved areas, bolstering scholarship support and creating a learning environment supportive of each student’s success.

It also includes a novel admissions tool getting attention across the nation: the school’s socio-economic disadvantage metric, which is being trademarked as the UC Davis Scale. The metric incorporates elements such as family income and receipt of need-based scholarships during college. These elements provide a fuller picture of each applicant’s educational opportunities along their way to medical school.

UC Davis’ admissions success also comes from paying greater attention to the lived experience of applicants. The School of Medicine stays focused on its social mission of training doctors to advance health equity, a longstanding priority for the school.

“We’ve figured out how to stay true to the mission of a public institution, the bedrock on which we’ve navigated the past quarter century despite California’s 1996 ban on affirmative action,” Henderson said. “Our school is three times more ethnically and racially diverse than the national average, and that diversity helps us better meet our state’s health care needs.”

The beginning of a transformation

Henderson was practicing primary care internal medicine at an academic medical center in San Antonio and overseeing its internal medicine residency program in 2000, when he and his wife, oncologist Helen Chew, were recruited to UC Davis. He was tapped to lead the School of Medicine’s own internal medicine residency program and employ his knack for recruiting talented medical school graduates.

When he was promoted to associate dean for admissions in 2007, he worked with admissions committee faculty and staff to improve the efficiency and integrity of the process to evaluate over 5,000 applicants to UC Davis each year, all while focusing on meeting California’s health workforce needs. This included partnering with IT to design a secure web-based admissions portal that was both user-friendly to applicants and easier for admissions committee members to navigate.

“Here we were, UC Davis, competing against Stanford and UCSF, a David vs. Goliath situation,” Henderson said. “We needed to make substantial investments to update our process and attract the best candidates to fulfill our school’s values and mission.”

Socioeconomic status in admissions

With a new electronic admissions system in place, the admissions team turned their attention to holistic admissions.

Every school relies on an applicant’s Medical College Admission Test, or MCAT, score, and undergraduate grades, to help determine who gets accepted. But UC Davis takes a broader view of those metrics by examining each applicant’s life experience including barriers encountered or “distance traveled.” What did it take for the student to get to college? Did they serve in the military? Did they overcome a major illness?

Students who come from low-income families or attend community college have been underrepresented in medical schools for decades. These students also have a strong desire to serve populations lacking access to care and are more likely to go into much-needed specialties like family medicine, often in rural communities where residents face serious health inequities.

The UC Davis Scale helps the school select students who seem motivated to spend their medical careers in underserved areas — something an MCAT score or GPA cannot do.

Novel interview practices at UC Davis School of Medicine

UC Davis was one of the first schools in the country to incorporate the MMI, or Multiple Mini Interview, into its admissions process.

Unlike traditional admissions interviews led by a doctor or medical student and lasting about 45 minutes, the MMI takes place in a mock clinic setting and consists of visits to multiple stations, each lasting eight to 10 minutes. The person evaluating the candidate, known as a rater, could be a professor, staff member, student, even a community member. The rater knows nothing about the applicant, which removes a bias inherent in traditional or open-file interviews, such as knowledge of the undergraduate institution or academic record, which are considered elsewhere in the process.

The rater may also observe how the applicant interacts with a “patient” who is actually a trained actor. The scenario might simulate a thorny ethical issue or volatile situation to assess the applicant’s problem-solving and communication skills.

“The MMI illuminates how an applicant’s life experiences, thought processes and maturity can affect their performance in realistic situations, which written examinations cannot do,” Henderson said.

Pathways to diversity in health care

When students enroll at UC Davis School of Medicine, they can apply to join any of five Community Health Scholar pathways, or tracks. Each pathway meets a pressing workforce need, such as the shortage of primary care physicians. About 30% of each incoming class enrolls in a pathway, some of which have received state or other external funding including from the American Medical Association.

The pathways:

-

Rural PRIME, which provides medical training in rural areas of California

-

TEACH-MS, for students who want to practice primary care in urban underserved settings

-

REACH, which offers Central Valley training opportunities in and around Modesto

-

ACE-PC, a partnership with Kaiser Permanente that allows primary care-bound students to attain their medical doctor degree in three years instead of four

-

Tribal Health PRIME, the newest pathway for students seeking to care for Native American communities

The pathways pair students with clinical sites and residency programs similarly committed to filling critical workforce needs. Graduates of pathway programs are much more likely to choose careers in primary care and to practice in underserved areas of California.

“Pathway scholars, like most of our students, have unique attributes that demonstrate grit, resilience and persistence in their pursuit of medicine despite adversity,” said Shadi Aminololama-Shakeri, a radiologist and chair of the medical school’s admissions committee. “These students have a deep commitment to improving health outcomes in the vast rural, agricultural, and underserved urban settings across California — communities many of them are strongly connected to.”

Aside from the five pathways, UC Davis leads an effort that brings together several Northern California campuses to assist community college students to become doctors. AvenueM, a program funded by the California Department of Health Care Access and Information, supports community college students to transfer to a four-year university and then guides them toward medical school.

The Davis Scale: An innovative holistic admissions metric

Dozens of universities have reached out to the UC Davis School of Medicine to inquire about holistic admissions and the UC Davis Scale, which is made up of eight factors, including parental education level, family income and whether the applicant grew up in an underserved area.

“The scale helps put applicants’ GPA and MCAT scores into context of the economic and educational opportunities that influence these traditional metrics,” Henderson said.

The scale was developed by researchers Joshua Fenton, Anthony Jerant and Peter Franks from the UC Davis Health Department of Family and Community Medicine.

According to the AAMC, one in four medical students in the U.S. come from families with incomes in the top 5%; and very few students come from lower-income families. And a study co-authored by Tonya Fancher, the UC Davis associate dean for Workforce Innovation and Education Quality Improvement, found that applicants whose parents earn less than $50,000 a year are half as likely to be accepted into medical school than those earning greater than $200,000, even if they’re just as academically qualified.

“Medical schools have largely excluded low- and middle-income kids,” Henderson said, “and we need to change that if we want to graduate the physicians our state and country needs to address health inequities.”

Henderson, Fancher and Susan Murin, the UC Davis School of Medicine interim dean, published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association late last year summarizing the school’s approach to redesigning admissions. The article noted that 60% of UC Davis medical students come from families who earn the median U.S. income or less, compared with 24% nationally.

“These students’ life experiences are as valuable as their academic credentials in the fight against health disparities,” the article stated.

“Leveling the playing field for low-income students can reduce segregation of medical schools, enhance the impact of scientific teams, grow the primary care workforce, improve access to care for underserved communities, and increase provision of culturally humble care,” the article stated. “All medical schools must recommit to their social mission if the U.S. is to achieve health equity.”

Future aspirations for the physician workforce

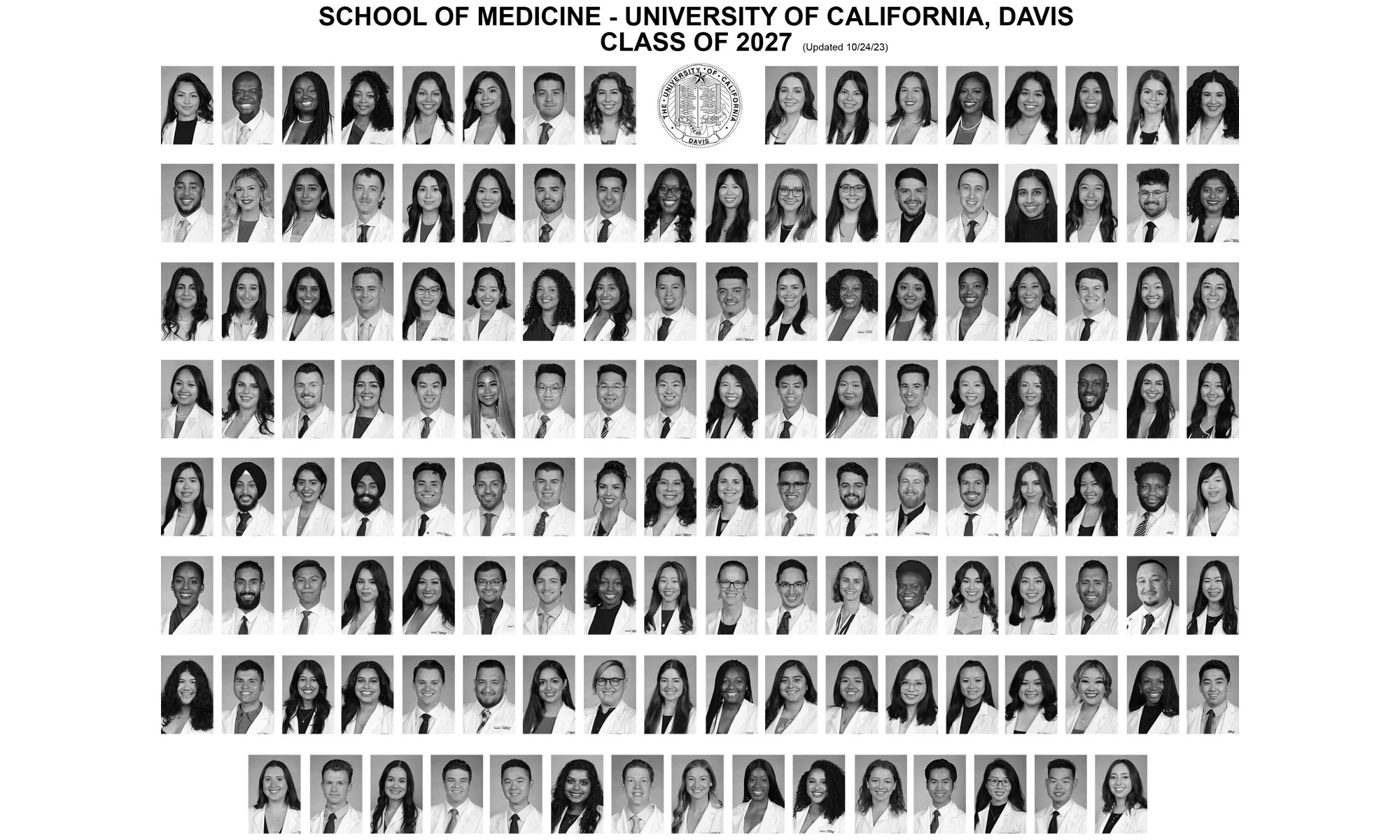

On average, about 7,500 students now apply to medical school at UC Davis each year. Typically, less than 3% are accepted. The first-year student body that entered last summer is 57.7% female. The newest class is 24% Hispanic/Latinx, 13.1% Black/African American and 5.1% American Indian/Alaska Native — the major groups historically underrepresented in medicine.

Seven out of 10 UC Davis students come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. Nearly 40% of the first-year students got their application fees waived for financial reasons, compared with 13% nationally.

Approximately 45% of the new students were among the first generation in their family to attain a college degree, the highest proportion of all U.S. medical schools, as compared to the national average of 15%, according to AAMC data. It’s a statistic that UC Davis pays close attention to, given that such students have unique assets and needs, and because many aspire to be physicians in underserved communities.

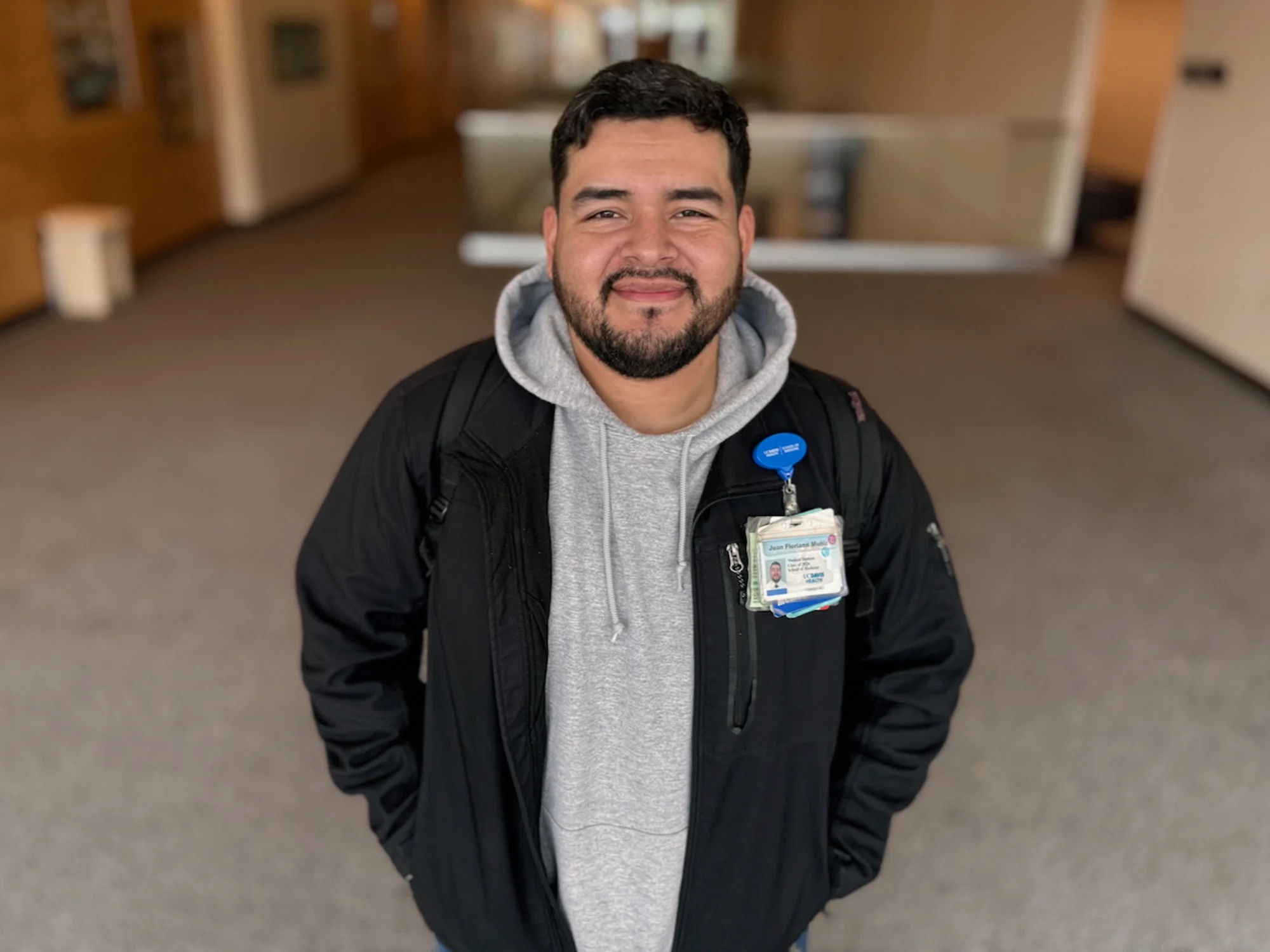

Juan Floriano Muñiz is one example. A son of Mexican immigrants born and raised in agricultural Colusa County north of Sacramento, Floriano Muñiz aspires to care for farmworkers and other vulnerable populations in his home community. According to a 2021 report by the California Health Care Foundation, Colusa County has just three primary care doctors per 100,000 residents — the third lowest ratio in the state.

“I want to practice medicine there because there’s a need for more accessibility in health care in these rural communities, and I feel I can fill that gap,” said Floriano Muñiz, a second-year student who is from Williams, a majority Latino city of about 6,000 people. “Plus, my family is still there, and I have this sense of wanting to be at home where my upbringing was shaped.”

Floriano Muñiz, who worked on and off as a farmworker, like his father and grandfather, attended Sacramento State University for his undergraduate education and got accepted by three medical schools. He chose UC Davis in part because of the opportunities to train in rural hospitals and clinics, a requirement of his Rural PRIME pathway.

As a greater share of lower-income medical students have opted to attend UC Davis, the school has responded by bolstering financial aid, providing $12 million in annual scholarships for those with financial needs.

In addition, the school offers academic and mental health support to the entire student body, including academic coaches, resources from the Office of Student and Resident Diversity and opportunities to connect with mentors. The school also encourages participation in dozens of student organizations and student-run clinics that provide free care to underserved patients.

“I’m really proud of UC Davis because we were one of the first medical schools to drastically reform our admissions policies to better match our social mission, and we now can see that our hard work is paying off,” Henderson said. “As a result, the doctors we graduate are able to better care for the California communities who most need them.”

Media Resources

Media Contact:

- Edwin Garcia, UC Davis School of Medicine, 916-734-9323, edmgarcia@ucdavis.edu