Emilia Barrosse, UCLA

Hidden away in the history department student lounge on the sixth floor of Bunche Hall is one of UCLA’s greatest treasures, but not many people know it. On the far side of the room, a mural covers the wall from corner to corner, from floor to ceiling — an apocalyptic scene from some future century.

Enigmatically entitled “S.P.Q.R.” (initials that refer to the ancient “Senate and People of Rome”), the mural depicts the UCLA research library in ruins, presumably after a big earthquake wipes out Los Angeles and the language of the region mysteriously reverts to Latin. It is one of the last remaining works of the acclaimed muralist Terry Schoonhoven and the LA Fine Arts Squad, the internationally renowned street art group he helped found.

The painting is one of the few murals associated with the LA Fine Arts Squad that has lasted over the years because it has been protected indoors.

“The fact is that none of their other murals are still extant — or barely visible — because they are out in the Southern California sunlight and have faded or been destroyed,” said UCLA emeritus history professor Thomas Hines, a member of the departmental committee that commissioned Schoonhoven, a UCLA graduate, in 1975 to paint the mural.

“The thing that makes this [mural] so important is that it’s not exposed to the elements — it’s still there,” said Hines, who’s penned several books on modern art and architecture in California. “And, therefore, it is of all their work, the mural you can still see.”

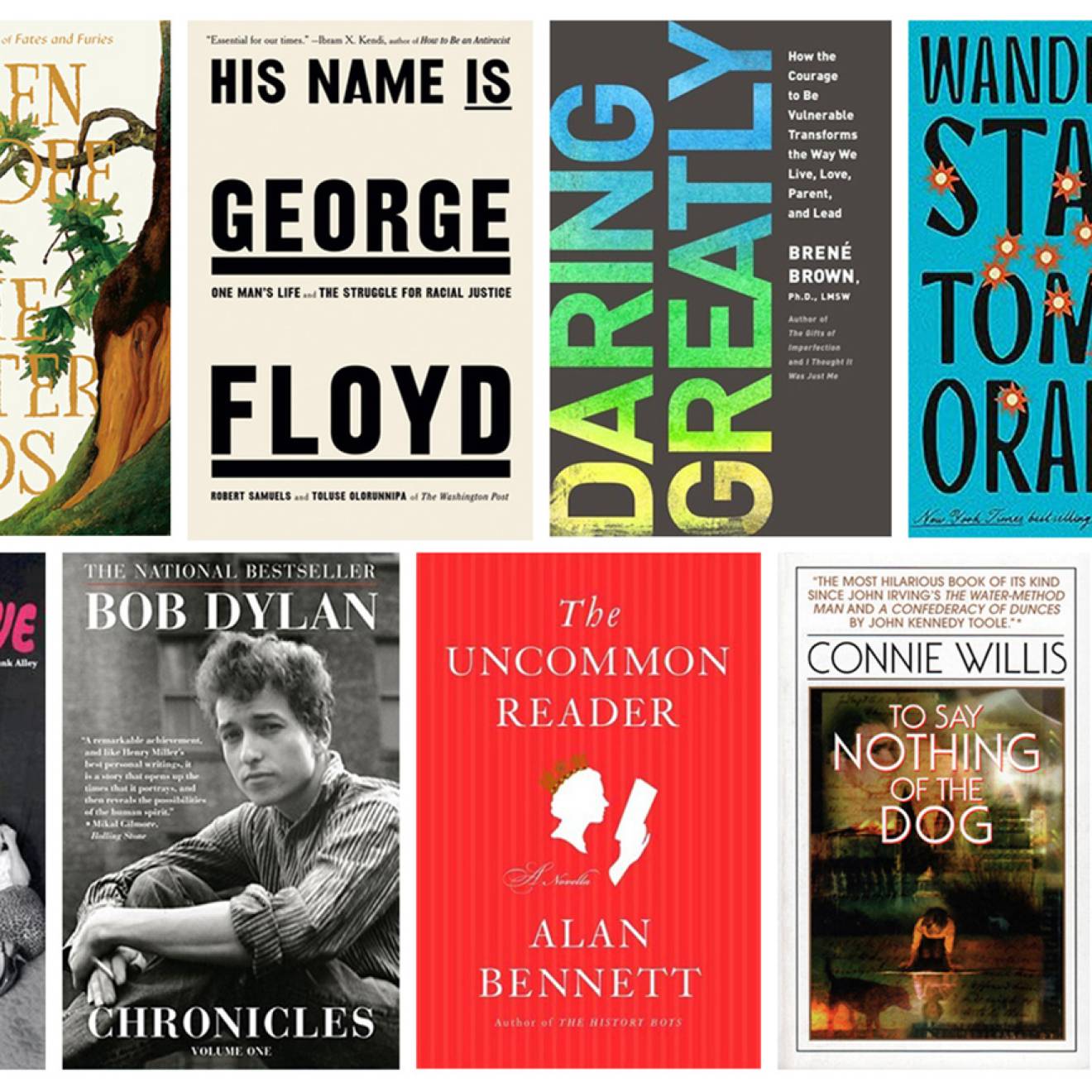

Because of the painting’s excellent condition, the viewer can glimpse an amusing detail: On the floor of the rooftop of a nearby building lies a crumpled concert program of “Ancient American Music” featuring the work of Aaron Copland, Bob Dylan and John Cage.

Apocalyptic visions

Schoonhoven and the LA Fine Arts Squad were responsible for a number of murals that once freckled the streets of Los Angeles in brilliant colors. Their works focused on apocalyptic topics that placed Los Angeles in shocking climates and scenarios. Their 1970 mural “Venice in the Snow” presented the vibrant, sun-soaked Venice Boardwalk covered in snow. “Isle of California,” perhaps their most well-known piece, features a shattered fragment of a freeway overpass hanging precariously off the side of a mountain. One Schoonhoven painting on canvas, “Los Angeles Under Water,” is in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

But their murals, along with many others crafted over two decades, have now faded along with the memory of the acclaimed art troupe’s legacy. But Hines refuses to let their achievements be forgotten.

“We need some record so that everything isn’t obliterated or torn down with each generation,” said Hines. “The Fine Arts Squad was a part of a cultural layering, and they were very important in the '60s and '70s in Los Angeles, and, with Schoonhoven, into the ’80s. If everything were intact, you’d write a story of their work, with [“S.P.Q.R.”] being one example. But that’s not the case — [this is] the only one left.”

Significance forgotten

In the past few years, Hines realized that UCLA students and faculty had lost sight of the significance of the Bunche Hall mural, so when the history department decided it wanted to renovate the student lounge in the spring of 2013, he wanted to make sure the mural was treated with the respect it deserved.

Hines immediately went to David Myers, chair of the Department of History, to have a conversation about the mural’s unique place in Los Angeles art history.

“Professor Hines helped me understand a little better the artistic end and the historical dimensions of [the mural],” Myers said. “And what I didn’t really appreciate as a landmark, I came to understand as exactly such. Then I came to understand who Terry [Schoonhoven] was and who the Fine Arts Squad was and why this was an important piece of public art that we have a particular mission not only not to be indifferent to, but also to really protect and be proud of.”

Over the years the mural had suffered some wear and tear as students, unaware of its importance, backed chairs and tables into it. Hines and Myers decided that it was time for the mural to undergo a restoration. They called upon Amy Green, a Mid-City art conservator, to take a look at it.

“Tom Hines gave me some interesting inside information about the history of the mural,” Green said. “He wanted me to know that it’s significant because a lot of people thought that it was something some disgruntled students might have done in their spare time. [But] it’s an actual work of art that was painted by a recognized artist with a point of view and a recognizable style.”

Preserving cultural history

Green consulted a mural conservator to determine the most appropriate, least invasive method to remove surface dirt.

“It’s hard to put into words why art is important — it’s something I struggle with all the time,” Green said. “But in terms of conserving and preserving [art] — our material culture is all we have to offer insight to the future generations, and it tells our history as well as anything.”

Now the mural sits as vibrant as ever behind red velvet stanchions. On display is an introductory piece written by Hines detailing the painting’s place in the history of L.A. art.

“[The mural] has an interesting mix of allusions to the past and the future, and I think, in a certain sense, that’s what we are concerned about in the history department today,” Myers said. ”We’re passionately concerned about understanding the past but with the ultimate goal of better understanding the future. So it’s an interesting reflection both of the fragility of life, [and] the mission of the historian.”