Here’s a camera, now tell a purposeful story.

That’s the opportunity UCLA’s Center for EthnoCommunications presents its students.

Established in 1996 by filmmaker Robert Nakamura at the Asian American Studies Center, the students and faculty have built a program that goes beyond the classroom. With deep roots in Asian American and minority activism, EthnoCommunications students learn the craft of documentary filmmaking and how to give communities a voice through film.

Renee Tajima-Peña

With the guidance of seasoned faculty, students turn their lens both inward and outward to discover their place and voice amid a turbulent global pandemic and increased violence toward Asian Americans.

The center draws graduate and undergraduate students from across the UCLA campus with diverse perspectives and majors, in addition to Asian American Studies. These budding filmmakers produce work that challenges the boundaries of personal identity to ask broader questions about immigration, gender identity and what activism means today.

At the helm of EthnoCommunications is activist, filmmaker, producer and professor of Asian American Studies at UCLA Renee Tajima-Peña.

An influential figure in documentary filmmaking, Tajima-Peña has directed groundbreaking films such as “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” (1987) and “No más bebés” (2015). She most recently produced the five-part documentary series “Asian Americans,” which premiered on PBS in May 2020. She brings her own treasure trove of experience and mentorship to her students.

“You’ve got to find your own voice. Everybody has their own sensibility. Maybe it’s more conceptual and experimental, maybe it’s humor, maybe it’s journalistic,” she says. “We encourage them to express themselves creatively through their own individual kind of lens, and don’t feel you have to do what we do.”

Tadashi Nakamura, faculty and son of founder Robert Nakamura, and Janet Chen, filmmaker and center assistant director.

Students are challenged to think about video as a medium for self-discovery, says Janet Chen, documentary filmmaker and the assistant director of EthnoCommunications. “Our students have always told us how much they learn, not just about making a video, but thinking about themselves and thinking about their own identities and communities.”

Chen and Tajima-Peña form a continuum of filmmakers and storytellers at UCLA stretching back to the civil rights era activists of the late 1960s, who fought for racial justice on campus and in academia.

The fight for inclusion

The seeds for EthnoCommunications were planted in 1968 when a group of faculty and students — dubbed the Media Urban Crisis Committee (MUCC) — advocated for affirmative action initiatives in UCLA’s film program.

Amid a time of social unrest in the United States, and shortly after the Watts Rebellion, students from Asian American, Chicana/o, Black and Native American backgrounds sought equal representation in media as well as social justice in university programs.

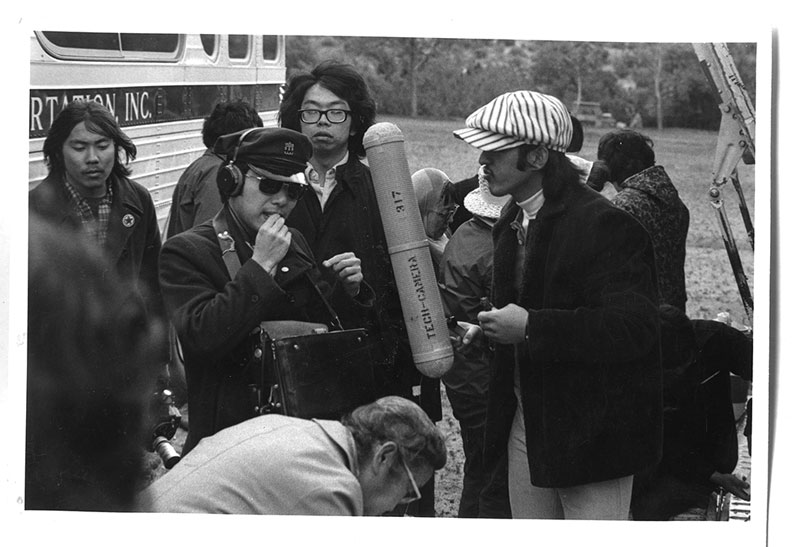

Students from UCLA's Ethnocommunications graduate film program documenting the Pioneer Project's field trip taking Japanese American seniors to Lancaster to view wildflower in bloom circa 1971. From left to right, Duane Kubo, Alan Ohashi, Steve Tatsukawa and Mike Murase.

Elyseo Taylor, the first African American faculty member in UCLA’s theatre arts department, helped formalize MUCC into an academic program, known as EthnoCommunications, which trained diverse students in mastering film and media communication. The short-lived program dissipated by 1973, due to a backlash over affirmative action and dwindling resources.

But one of its earliest students was Robert Nakamura, who today has the well-earned reputation as the “godfather of Asian American media” and who went on to found today’s incarnation of the EthnoCommunications program.

His credits include “Manzanar” (1972), a landmark film that revisits his memories of the World War II incarceration camp in California, and “Hito Hata: Raise the Banner” (1980), a narrative about the lives of Japanese Americans in the United States.

In 1970, Nakamura, together with Duane Kubo, Alan Ohashi and Eddie Wong, founded Visual Communications (VC), the first nonprofit dedicated to accurate and positive portrayals of Asian Americans in media. Still going strong today, VC will present its 37th Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival in September 2021.

Nakamura “made the first photo exhibit and film on the Japanese American World War II experience,” says his son Tadashi “Tad” Nakamura. “And his photo installation was the first time that any evidence or any photos of the camps were publicly displayed. He also went on to make the first narrative feature film done by and about Asian Americans.”

An influential filmmaker in his own right — Tad Nakamura’s credits include award-winning films such as “Jake Shimabukuro: Life on Four Strings” — the younger Nakamura is among the renowned faculty of the present-day EthnoCommunications program, continuing his father’s work of teaching UCLA’s next generation of would-be filmmakers.

“It’s wanting to carry on his legacy, wanting to carry on the work that he started, and that includes helping other filmmakers discover their own voice and their own mission through film,” Nakamura says.

Watch Manzanar (1972), a short film by Center for EthnoCommunications founder Robert Nakamura. Courtesy Tadashi Nakamura on Vimeo.

Filming activism, identity and community

Today’s EthnoCommunications students make documentary stories exploring their communities and identities. Such stories include Hannah Joo’s profile of community activist and comedian Kristina Wong, Emory Johnson’s film about a transgender student who undergoes gender affirming surgery and May Kono’s documentary about discovering activism through the UCLA Taiko Kyodo drumming group.

Hannah Joo, a master’s student in Asian American studies at UCLA, is keenly aware of EthnoCommunications’s history and social documentary lens.

“I came into the class and was pleasantly surprised in how EthnoCommunications and independent filmmaking in Asian American communities, especially in L.A., had such a deep history of racial justice for Asian Americans,” Joo explains, adding “EthnoCommunications focuses on social documentary, or this method of creating stories for us, by us.”

Kristina Wong works on a sewing project.

In her own project, she followed community organizer and comedian Kristina Wong to document her performance in February 2020 about being an elected official in L.A.’s Koreatown. As the pandemic gathered storm, Joo followed Wong’s shift in focus from city governance to full-on crisis management.

To help address the shortage of safety gear early in the pandemic, Wong formed what would be called the Auntie Sewing Squad, which started with volunteers making masks in their own homes and grew into an endeavor that shipped tens of thousands of masks to vulnerable communities.

As Joo’s project evolved, she uncovered historical parallels in telling Kristina Wong’s story.

For example, Joo saw how garment workers who were women of color or Asian American had been able to transform sewing work into activism, both past and present, using their jobs to organize. “It grew into this project with Kristina still as the main focus, but with deeper understanding of the histories of anti-Asian racism in the U.S.,” Joo says.

Emory Johnson, meanwhile, dove into a more personal subject about queer identities and the process of becoming.

“I was able to develop a short documentary about a first-year college student and Star Wars fan [named Jesse] who undergoes top surgery and explores the gender spectrum with the support of their friends,” Johnson says.

Johnson, an MFA student who is also trans, observes that in their own process of coming out as trans they did not have a particular outlet to express identity creatively.

“EthnoCommunications gave me the environment to explore that side of me through telling the story of Jesse,” Johnson says.

Jesse, of Emory Johnson's film.

Similarly, undergraduate student May Kono also explored identity and activism in her work on the strong community bonds that form in Kyodo Taiko, the name of a long-established taiko drumming group at UCLA. A member of Kyodo Taiko, Kono wanted to explore how the art form exposed her to Asian American activism.

Having grown up in a predominantly white community, Kono observes, “Nobody ever told me about anything Asian American or activism-related during high school, middle school, and it was only in college that I experienced it through Kyodo.”

Kono’s documentary project also evolved along with the pandemic.

Kyodo Taiko at Manzanar, site of the Japanese internment camp and subject of Robert Nakamura's 1972 film.

“We obviously cannot have drums in our own homes,” Kono laughs, adding “I’m focusing on this one event we’re going to have at the end of the quarter and trying to make that event into a fundraiser for Stop AAPI Hate.”

In documenting their stories, students like Kono, Joo and Johnson carry on the history of empowerment through visual storytelling.

“My dad was really adamant about trying to ground his students in what EthnoCommunications meant for him; it was making films not about representation and not about explaining ourselves to others so much as explaining ourselves to ourselves,” says Tad Nakamura.

Connecting history from past to present

In addition to mentoring the next generation of storytellers and documentarians, EthnoCommunications also houses its own unique documentary projects in which many of the students participate.

One of these is the Collective Memories Project, a series of extended interviews with pioneers of the Asian American movement, with notable interviewees such as congresswoman Judy Chu of California’s 27th district and criminal defense attorney and activist Mia Yamamoto. Projects like this both teach and inspire the next generation to carry on the work.

Filming “Mia Yamamoto” by Janet Chen, produced for UCLA Asian American Studies Center’s Collective Memories Project. From left to right, UCLA student Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez, UCLA student Alma E. Villa Loma, Mia Yamamoto, Pasadena City College professor Susie Wong and EthnoCommunications assistant director Janet Chen.

Listening to Yamamoto — a transgender woman who was born in the Poston Relocation Camp in Arizona — particularly resonated with Joo. “Just hearing her talk about her time at UCLA and just the ways that she’s been connecting that work back in the `60s and `70s and how it’s still relevant today with all the police brutality, the Black Lives Matter protests … something rings in you when you listen to an elder tell you this work has been going on for decades.”

EthnoCommunications is also forward-looking, engaging in new media and embracing emerging formats to convey contemporary issues.

The Nikkei Democracy Project, in partnership with a collective of artists and activists, exposes current threats to U.S. constitutional rights through the lens of Japanese American internment. It shifts the focus of documentary work from longform features to micro-videos you can watch on your phone. One aspect particularly highlighted by the videos is the power of collaboration across different communities in addressing systemic racism.

Videos include stories about families with members who are undocumented and protests of the 2017 travel restrictions placed on majority Muslim countries.

Renee Tajima-Peña recognizes the power of building interracial solidarity across communities who have historically been marginalized. “Let’s say my primary identity is as an Asian American and then as a filmmaker and a teacher. But then I see my beloved community as being this larger community,” says Tajima-Peña.

In that same spirit of solidarity, EthnoCommunications faculty and students will launch the May 19 Project, produced by Tajima-Peña and the writer and cultural strategist Jeff Chang, during Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month on May 19.

With original videos and content geared for viewing on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, the May 19 Project aims to amplify stories of communities and people who work for justice as well as calls to act against systemic racism.

The project emerged from the compounding events of the past year, which include a sharp rise in anti-Asian violence (the recent horrific murders of six Asian women in Atlanta, for example) and a massive outcry for justice in the protests sparked by George Floyd’s murder.

With a renewed sense of urgency and commitment to end systemic racism also comes hope. Through the lens of EthnoCommunications, archiving the past and documenting the present informs and engages how these issues can be addressed or even overcome.

Top photo: From the Nikkei Democracy Project — “Vigilant Love” by Tani Ikeda, produced by Nikkei Democracy Project (Tani interviewing Sahar Pirzada, a UC Berkeley alum).