Tom Vasich, UC Irvine

On Feb. 12, Facebook rolled out a new feature called Legacy Contact, which gives people a platform for remembering and celebrating the lives of loved ones when they die.

The basis for this product came from the doctoral work of Jed Brubaker, a doctoral candidate in informatics at UC Irvine. Indeed, the Menlo Park, Calif., social media giant even retained Brubaker as an academic consultant in the creation, testing and release of Legacy Contact.

“This area — the role death plays in social networking — is my expertise, and Facebook has taken five years of my research and translated parts of it into this important feature,” Brubaker says. “This has been an incredible opportunity to support the development of a product that can help millions of people.”

Credit: Steve Zylius/UC Irvine

“This has been an incredible opportunity to support the development of a product that can help millions of people,” says Jed Brubaker, a doctoral candidate in informatics at UCI.

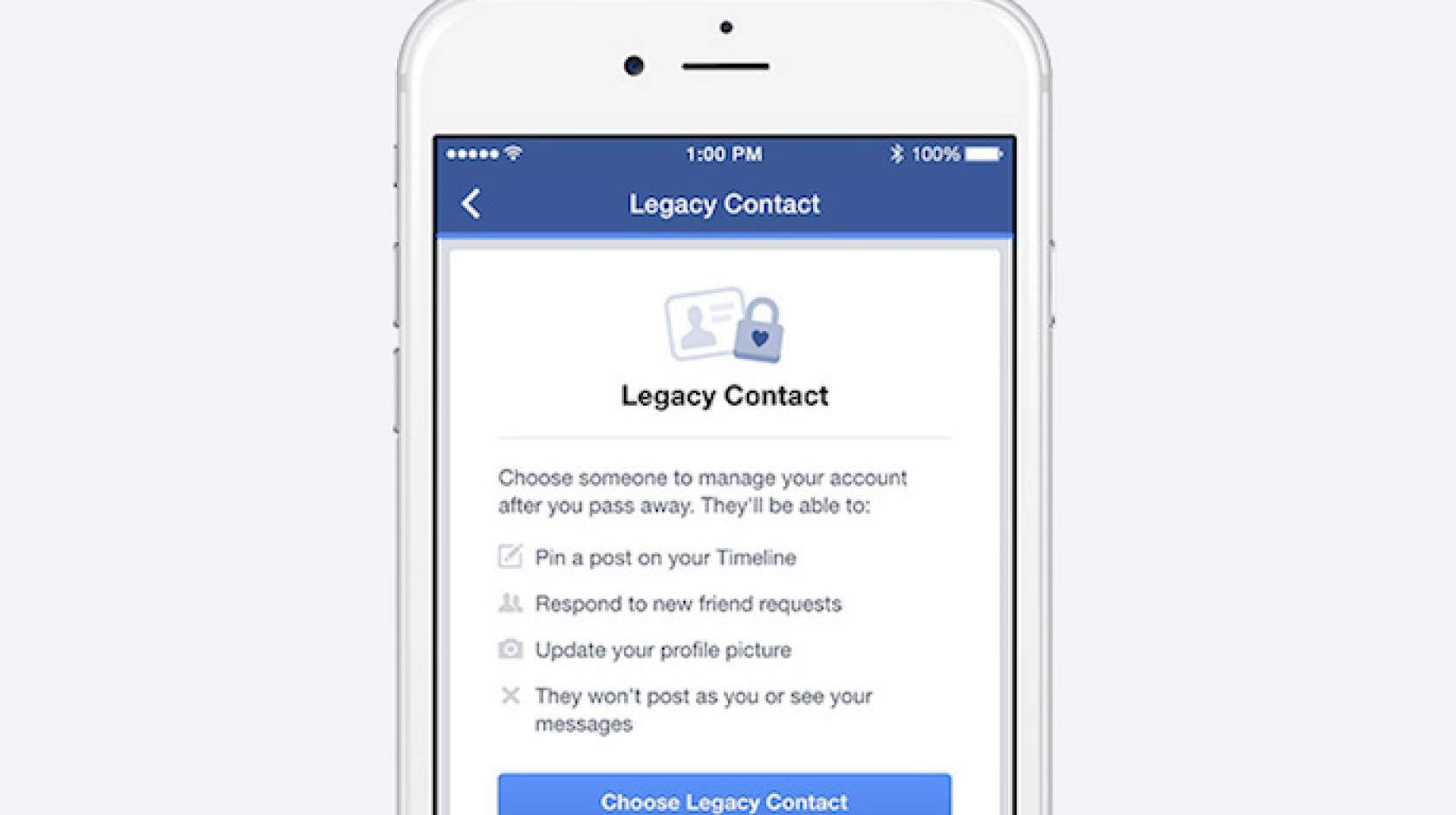

Here’s how it works: Legacy Contact allows individuals to decide what happens to their Facebook account when they die. Through their security settings, they can assign a “legacy contact,” or steward, to manage the account.

On behalf of the deceased account holder, the legacy contact is able to post an obituary or message, update profile pictures and cover photos, respond to new friend requests, and moderate the posting of condolences and memories from existing friends.

With additional permission from the account holder, the legacy contact can download an archive of profile information and posts. Facebook will also make changes to “memorialized” accounts, adding the word “remembering” before the person’s name.

“Memorialized profiles can be unsettling, particularly right after someone dies,” Brubaker says. “It’s not always clear that someone has died, and details can get buried in the flood of messages that friends post.”

The alterations to the memorialized account are intended to reduce ambiguity and provide a more supportive environment for the community.

Gillian Hayes, the Robert A. & Barbara L. Kleist Chair in Informatics and Brubaker’s Ph.D. adviser, says there are a growing number of collaborations between information & computer science researchers and Facebook, in part spurred by the successful partnership between Brubaker and the company’s research team.

Brubaker first published a study involving Facebook in 2013. In May 2014, he released one called “Stewarding a Legacy: Responsibilities & Relationships in the Management of Post-mortem Data” that advanced postmortem solutions meeting the needs of both account holders and their survivors.

This concept of stewardship, Brubaker says, centers on individuals caring for accounts and data they do not own. People’s social media identities persist after they die, and even though no one is managing their profiles, others continue to use these spaces.

In the context of Facebook, stewardship provides a way to tend postmortem accounts and balance the needs of the dead with the needs of those left behind. Additionally, stewards let the online community collectively grieve and memorialize a departed loved one.

Facebook product developers took into consideration Brubaker’s insights and adopted some of his recommendations in determining how best to improve the memorialization experience and give people more after-death control over their accounts.

“When Jed came to UCI to work on his doctorate, we talked about the impacts he wanted to have,” Hayes says. “It wasn’t only to do research, but to work with people and really change things. So to help roll out a product that will help billions is amazing.”

“I feel really strongly about my research serving the communities I work with,” Brubaker adds. “Over the last six years, I’ve worked with many people during some of the most difficult parts of their lives. It’s great that my research is having an impact, but mostly I’m grateful to the people who were willing to share their experiences.

“The most gratifying aspect of Facebook’s new features is knowing that these changes will make Facebook a more supportive space for people during challenging times.”