Janet Byron, UC Newsroom

As 2021 drew to a close, residents and community leaders in Kettleman City were getting increasingly nervous. After receiving only 5 percent of their annual state water allocation and with no additional allocations on the horizon, the small, unincorporated farmworker community midway between Fresno and Bakersfield was due to run out of water by the end of the year.

“They appealed to the Department of Water Resources for emergency supplies and were granted 96 acre-feet, but that would only cover about 30 percent of their needs,” says Kristin Dobbin, assistant professor of cooperative extension in the UC Berkeley Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management. “They were caught completely surprised.”

While Kings County officials eventually were able to purchase the additional water that Kettleman City needed at a high cost from a Southern California water district, the episode was a harbinger of the challenges that disadvantaged California communities could face to meet their water needs as the frequency, duration, and intensity of droughts increases.

“In a state that affirms the human right to water — in law — that is not a position that we should be in,” Dobbin says.

California supplies water to about 40 million people, sustains the most productive agricultural region in the United States, and is a biodiversity hotspot. Dobbin is one of the lead researchers on COEQWAL, a 2-year, $9.1 million research project exploring ways to distribute California surface water more equitably among agriculture, cities and unincorporated communities, and the environment — in an era of rapidly changing climate.

COEQWAL is the largest of 38 climate action grants totaling $80 million that were funded by the State of California via the University of California, with the goal of having “swift and measurable impacts on climate resilience.” The project aims to use sophisticated water and climate modeling to begin to provide California with state-of-the-art, transparent and publicly accessible water planning and stewardship tools.

“Our water management system in the Sacramento and San Joaquin river basin is much more vulnerable than people think,” says UC Berkeley’s Ted Grantham, principal investigator of COEQWAL, which stands for “Collaboratory for Equity in Water Allocations.” “When you realize that the status quo is not going to serve us well into the future, that’s an entry point to make changes.”

In the first phase of COEQWAL, researchers will focus on three main areas: access to drinking water for communities that depend on surface water, Chinook salmon recovery and salinity management in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

“California’s methods for parceling out water were built for a previous era, and not our new climate of worsening droughts and extreme weather,” says Theresa Maldonado, UC vice president for research and innovation. “These are the first steps toward correcting historical inequities in California’s water policies so that people in every corner of the state have access to the water they need for their lives, livelihoods and health.”

Prioritizing water needs

The state’s water infrastructure — the vast and complex network of dams, reservoirs, canals, pumps, and pipes that captures river water and redistributes it across the state — was constructed in the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century. Since then, California’s surface water has been distributed pretty much in the same order: agriculture first, cities next, then the environment.

Water deliveries are based on historic water rights, how much water is available in the state’s reservoirs and predictions about how much water various users will need. The state and federal agencies that divide up California’s water use a computer model created by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in the 1960s called CalSim (now in its third version) to help guide those decisions.

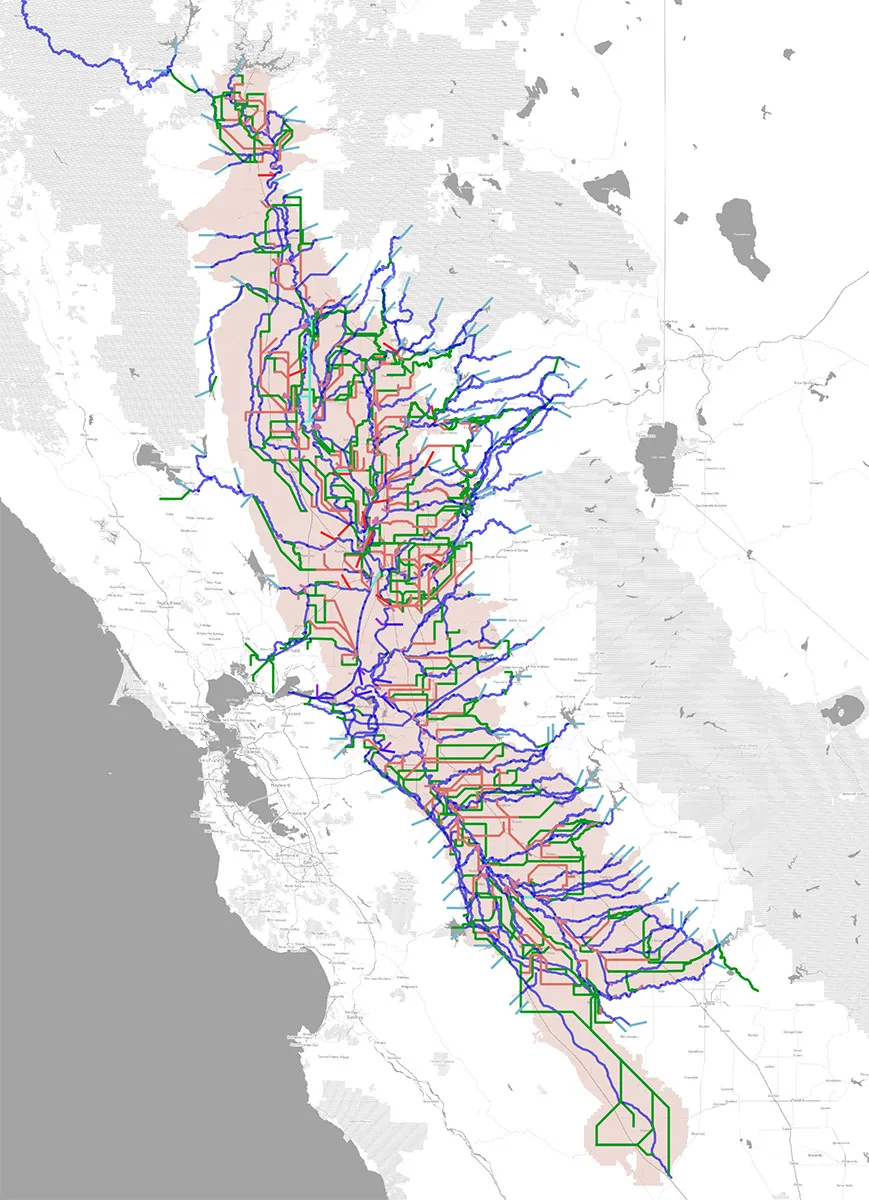

“The CalSim model is a representation of the large reservoirs, canals, and rivers that store and deliver to all major water users throughout the Central Valley, the Bay Area, and Southern California,” says Grantham, an associate professor of cooperative extension in the UC Berkeley Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management. “It simulates the ways in which the water system is operated.”

However, the CalSim model hasn’t kept pace with the state’s changing water needs and desires, and it doesn’t take into account how the climate is changing and will change in the future.

“CalSim assumes that the state’s water system will be operated in the future in the same way it’s been operated in the past,” Grantham says. “It’s used in a way that does not consider the full range of climate conditions that we’re likely to face, which means we’re underestimating risk to the system. It also doesn’t consider the wide range of options that exist for adaptation — for changing operations in ways that make water allocations more resilient and equitable.”

For example, when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and California Department of Water Resources use the CalSim model to explore options for biological opinions under the Endangered Species Act, the alternatives considered are often “bad, worse, or terrible” for salmon, Grantham says. “With this project, we are asking, ‘Aren’t there other alternatives that we can consider that might result in better outcomes for fish?’ We can tweak the knobs in CalSim and specify that instead of allocating to agriculture and cities and then environment, we can allocate to the environment first. We can then see what that means for the fish and for other water users in the Central Valley.”

In addition to considering novel ways to operate the system, the COEQWAL project is an attempt to bring the 21st-century realities of climate change to decision-making around water. Researchers from six UC campuses and California State University, Sacramento, will run the CalSim model with the best available climate predictions for temperature, weather, and myriad other factors, so that water allocation scenarios and associated tradeoffs can be explored under a range of future climates.

“CalSim tells California communities, ‘This is the only future that we can think about,’” says John Matthews, executive director of the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation and a member of COEQWAL’s advisory committee. “COEQUAL is a way of opening up that decision space, by recognizing that our values may be in a state of transition at the same time that the climate is in a state of transition.”

Ultimately, the COEQWAL project will develop an easy-to-use online data visualization platform, where users can see how water is delivered for each scenario and its associated consequences for people, the economy and environment. “We hope the resources that we develop for this project will play a pivotal role in enhancing community participation in water decision-making for California,” Grantham says, “which is essential for collectively making hard choices as we look to the future.”

More seats at the table

COEQWAL is collaborating with dozens of academics, including engineers, economists, ecologists, social scientists, climate scientists, and data scientists; as well as regulators, water suppliers, nongovernmental organizations, community groups and diverse water users, many of whom did not have a seat at the table when the United States and California were building the state’s water infrastructure and handing out water rights.

At that time, the state’s water-allocation equation simply did not include environmental needs such as flows in rivers for salmon to migrate and spawn; small, unincorporated communities that rely on surface water for drinking water; and historic and cultural uses, such as those practiced by California’s Indigenous people living on and around reservations.

“Appropriative water rights, which were locked in around 1914, did not recognize that Indigenous people had been relating to and using water since time immemorial,” says Emily Moloney, former water program coordinator with the Buena Vista Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians and a current member of the COEQWAL advisory committee. “Tribes were excluded from water rights.”

UC Berkeley’s Ted Grantham, Ph.D., is principal investigator of the COEQWAL project.

The Buena Vista Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians is a federally recognized Tribe with less than 50 members and the sovereign government of a 56-acre reservation in Amador County (the Tribe owns and manages 433 acres, in which traditional and ceremonial practices are used to sustain its resources). Its ancestral lands span a much larger area that includes parts of six counties from the eastern San Joaquin River Delta to the western slope of the Sierra Nevada between the Mokelumne and San Joaquin river watersheds, which includes numerous culturally significant waterways, village sites and fishing grounds.

“Because those waterways don’t flow through the tribe’s land, the tribe does not have riparian water rights or any adjudicated water rights to those water bodies,” Moloney says. “The tribe can no longer interact with those water bodies in the same way that it did historically, without private land ownership and boundaries blocking access.”

Moloney says that COEQWAL could provide the “proverbial sandbox” for understanding what the outcomes would be if, for example, river flows adjacent to the tribe’s land were improved for salmon and other cultural resources so that it is safe for tribal members to participate in water-based ceremonies in perennial streams on their land.

“In the tribal perspective, water connects all things in life,” she says. “Water is not seen as a commodity to be bought and sold or traded.”

Salmon are central to the cultural traditions of many California Tribal communities. The COEQWAL project seeks to ensure that rivers receive enough water for their salmon runs to thrive.