Dan White, UC Santa Cruz

Mummification was a sacred ritual of the ancient Egyptians, who called their mummified dead “noble ones.” But when mummies started showing up as supernatural archfiends in Victorian horror novels and rampaging ghouls in Hollywood movies, the original context got twisted beyond recognition.

How did these ancient artifacts transform into objects of dread, derangement, resurrection and occult power, and how have they been adapted and re-imagined through history, especially in the West, when mummy fiction and mummy movies became part of popular culture?

In their co-taught course, LIT 159M/HIS 159M: The Curse of the Mummy, UC Santa Cruz associate professor of literature Renee Fox and associate professor of history Elaine Sullivan are unwrapping those mysteries before a crowd of 220 students twice a week. “It's quite large for an upper-division course, but we expected a big turnout, especially with the option of taking it as a general education requirement and for different departmental credits,” Sullivan said.

This spooky, one-of-a-kind class grew out of a years-long friendship between Fox and Sullivan, with Sullivan reading Fox’s scholarly work on the Victorian fascination with the supernatural, and Fox immersing herself in Sullivan’s research on ancient Egyptian sites using 3D computer imaging.

The class feels like a match that was just waiting to happen, considering Fox’s and Sullivan’s surprisingly convergent credentials. Fox teaches classes in Victorian Studies, Irish Studies, the gothic, and popular culture. Fictionalized mummies have a strong presence in all of her subjects of interest. Sullivan, meanwhile, is an expert on the landscapes where actual mummies are buried. A self-described digital humanist, she has delved deeply into the Egyptian past by using technologies that provide new visual insights into the burial site of Saqqara and other landmarks.

Fox’s and Sullivan’s interdisciplinary approach provides students with an unusual dual perspective. By the time the undergraduates complete the course, they will know how and why mummies were made. But they will also have read and seen good and middling mummy stories and movies, and have a working knowledge of how mummy stories were adapted for political purposes, reflecting the preoccupations of 19th- and early 20th-century Europe, including the colonial perspectives of Victorian England.

During a recent class session, Fox screened a raucous trailer from a 1971 horror movie called “Blood From A Mummy’s Tomb.” “Resurrection, a rebirth in terror,” says a voice-over narrator in a loud and tremulous voice. “Complete control over life and death.” But the class, in spite of the syllabus’s tongue-in-cheek quality, has a serious purpose beneath its entertaining exterior.

“It's a textual analysis general education (GE) course, so we have history and literature majors, as well as students from other fields,” Fox said. “They’re all engaging deeply with the material, and it’s wonderful to bring together students with different interests — whether it’s gothic literature and monsters or ancient history and archaeology.”

“One of the sets of slides we put up on the first day is about how to read like a historian and how to read like a literary scholar,” Fox said. “We all close-read; we’re all attentive to language, and the kinds of audience being addressed. We’ll read primary source documents that can be examined from the points of view of both a historian and a literary scholar.”

As the class progresses, these students will use their imaginative and analytical skills to design an imaginary “mummy-inclusive” mid-19th-century display of ancient Egypt for the Victorian viewing public. Aside from displaying mummies, the students’ fanciful exhibits will also show the racial and gendered attitudes of Victorians towards the objects on display.

Victorian perspectives on mummies

The course dives deeply into Victorian literature and the 19th-century fascination with Egypt. Sullivan explains, “In the 19th century, we see the development of what we now consider scientific Egyptology. But even before we could read hieroglyphs, British and French museums were filled with Egyptian artifacts. Early Victorian writers imagined Egypt based on European fantasies.”

Fox continued, “Now we see these ancient artifacts and human remains under glass, and they feel very separate from us — they feel sacred. But that wasn’t the relationship Victorians had with these bodies coming back from Egypt. They were more accessible, more visible, more fantastical, and deeply bound up in the British colonial project, especially when Egypt became a protectorate of the British Empire in the early 1880s.”

Britain’s economic interest in Egypt, however, dates back even earlier, to the beginning of the 19th century. Since then, British tourists and explorers had swarmed over the country, seizing thousands of artifacts, including entire mummies, and bringing them back as souvenirs or treasures for display in England.

“This was emblematic of the political situation in the British imperial outposts,” Fox explained, “this idea of going into a place that didn’t belong to you, taking possession of its history via its antiquities, and remaking these stolen historical artifacts into symbols of British greatness and political power.”

In the midst of this plunder, it was fiction writers who grappled most forcefully with the guilt and anxiety of the time by imagining the dreadful supernatural consequences of seizing mummies.

“This literature explores the perils and ethical risks of taking possession of these artifacts — taking them out of their homelands—and imagines how outraged the mummies would be at these attempts to impose our own Western culture, our own life, onto them," Fox said. "In a lot of mummy literature, the mummies are out for blood."

“They fight back!” Sullivan interjected.

Fox elaborated, “By the time we get to the 1890s and the early 20th century, writers like Bram Stoker and Arthur Conan Doyle, who are creating stories about Egypt, have access to the latest knowledge. They can go to the British Library, read the scientific history of Egypt, and see what the curators of the Egyptian department at the British Museum are saying. They have access to cutting-edge Egyptological research.”

“But when they digest this information into their fictional work, it gets filtered through Victorian ideas about gender, colonialism, and themes like death, revival, and resurrection,” Fox said. "The knowledge about Egypt is transformed by a distinctly Victorian worldview. Many of these novels are fascinated by the intersection of magic and science in ancient Egypt, but they depict it through the lens of Victorian spiritualism — psychology, ghosts, and mediums contacting the voices of the dead.”

In addition to the gothic twist 19th-century writers applied to ancient texts, the course also offers a more nuanced view of what Egyptians actually believed about mummification and the afterlife. Students analyze Victorian literature about reanimation, including Dracula author Bram Stoker’s mummy novel, “The Jewel of Seven Stars,” but they read it in relation to ancient history as much as they do in relation to gothic literary tropes.

Sullivan added, “When I read Bram Stoker for the first time, it’s clear he’s drawing from the new discoveries coming out of Egypt in the late 19th century. He talks about a female pharaoh, whose temple the head of the antiquities department had recently excavated, and he inserts her as a character in his story. But then he transforms her into an evil queen who’s going to be reanimated by this British family. I find it fascinating that, while authors like Stoker are engaging with cutting-edge Egyptology, they’re reimagining it through the lens of literature.”

Fox and Sullivan emphasize that the Victorian view of mummies was often steeped in misconceptions. “For example, in mummy movies, including Brendan Fraser’s ‘The Mummy,’ there’s always a focus on the ‘Book of the Dead’ and dramatic horror,” Sullivan said. “But there was no actual Egyptian ‘Book of the Dead.’ The Egyptians never had books! They instead were writing a series of funerary spells on papyrus scrolls that focused on providing them knowledge for attaining an eternal, happy afterlife. The texts focused not on death, but eternal life.”

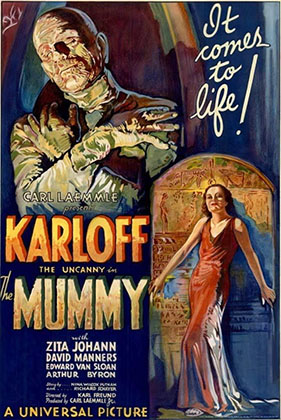

Professors Renee Fox and Elaine Sullivan holding up an image of a vintage poster for Karl Freund’s “The Mummy” from 1932.

Mummies in popular culture

A highlight of the course involves analyzing the portrayal of mummies in popular culture, including film. They will watch Boris Karloff as a living corpse in Karl Freund’s “The Mummy” from 1932, as well as the director Stephen Sommer’s 1999 reimagining also called “The Mummy” (1999) starring Brendan Fraser. Both professors are unabashed about their affection for the Sommers movie.

“Brendan Fraser's The Mummy is a movie I absolutely love with every ounce of my being,” Fox said. “It's fun, well-crafted, and beautifully written. Although it came out in 1999, it’s set in the 1920s and critiques the adventurer-archaeologists depicted in earlier films from the 1930s and 1950s. It critiques the colonial mindset of the time — how the West viewed the East and how British colonialism shaped perspectives on Egypt.”

Sullivan adds that the film’s commentary on colonialism makes it especially relevant. “It reflects how ideas of imperialism persist. The 2017 ‘Mummy’ reboot with Tom Cruise shifts the setting to 21st-century Iraq, where Cruise’s character is a U.S. soldier and an opportunistic antiquities looter. The film transfers the anxieties of imperialism from Egypt to other parts of the Middle East, showing that these power dynamics are still in play, just in different locations.”

A fruitful collaboration

This course has not only been rewarding for the students but also for the professors. Fox and Sullivan have found that their differing approaches — literary analysis and historical study — complement each other in unexpected ways. As Sullivan reflects, "We had conversations about this subject all the time for years, and at some point, we realized it would be fun to do something together. Our approaches intersect in ways that make the material even richer for students.”

Fox echoes this sentiment: “It’s been really fun for us to dive into deep learning from each other. I get to sit in on an Egyptology lecture, and Elaine gets to see literary close readings from my perspective. We’ve even talked about collaborating on something beyond the class—maybe co-editing a critical edition of Stoker’s ‘The Jewel of Seven Stars.’”

Both professors agree that their collaboration has been a delightful surprise. “Of course professors are always learning when we teach classes, but there's nothing like sitting in on an undergraduate lecture with a brilliant Egyptologist,” Fox said. “In co-teaching this class, I’m getting the chance to take a class I’ve never had the opportunity to take.”

Poster for Karl Freund’s “The Mummy.”