Glen Martin, California Magazine

UC Berkeley journalism professor Bill Drummond once met a nun who counseled Catholic priests bereft of their faith. Drummond was empathetic — with the priests, that is.

“Actually, I don’t think I know anyone in journalism education who hasn’t suffered a loss of faith,” says Drummond, who in a decades-long career covered the White House, worked as the Los Angeles Times bureau chief in New Delhi and Jerusalem, served as an associate press secretary for the Carter administration, and was one of the founding editors of National Public Radio’s news program Morning Edition.

“When I started my career, back when the Earth was cooling, I was something of an exception because I had a college degree,” says Drummond. “Many of the reporters and editors had learned their trade in the armed services — working at Stars and Stripes, for example. But they were tough and pragmatic and highly competent, and they took me down a peg. They had a profound influence on me, and I admired them tremendously.”

Now, says Drummond, “I teach in a graduate school that gives master’s degrees to kids in journalism, and the emphasis is more on software, on technology, than on the skills you need to get stories from people of all walks of life, to write on deadline, to line edit and copy edit. We’re teaching our students to talk to public relations people and politicians or — worse — each other, but they’re uncomfortable or even intimidated when they have to interview anyone on the street, anyone who doesn’t have a college education.”

In other words, to the trade’s detriment, journalists are ignoring H.L. Mencken’s dictum: The only way for a reporter to look at a politician is down.

“Citizens are alienated by the press because they feel that journalists are no longer part of working America, that they are too friendly with the elites they cover. It’s discouraging.”

Drummond’s reference to discouragement has a larger context than the mere triumph of social media over the Five Ws and One H, or press coziness with pols and their flacks. The general decline of the Fourth Estate, compounded by his wife’s death from breast cancer in 2003, ejected him into a very dark place. He doesn’t use the term clinical depression; an interviewer might be forgiven for inferring as much.

“As far as my career goes, I found myself looking back on 40 years as a journalist, trying to identify a story I wrote, any story, that made anyone’s life materially better,” he says. “I wasn’t able to think of one.”

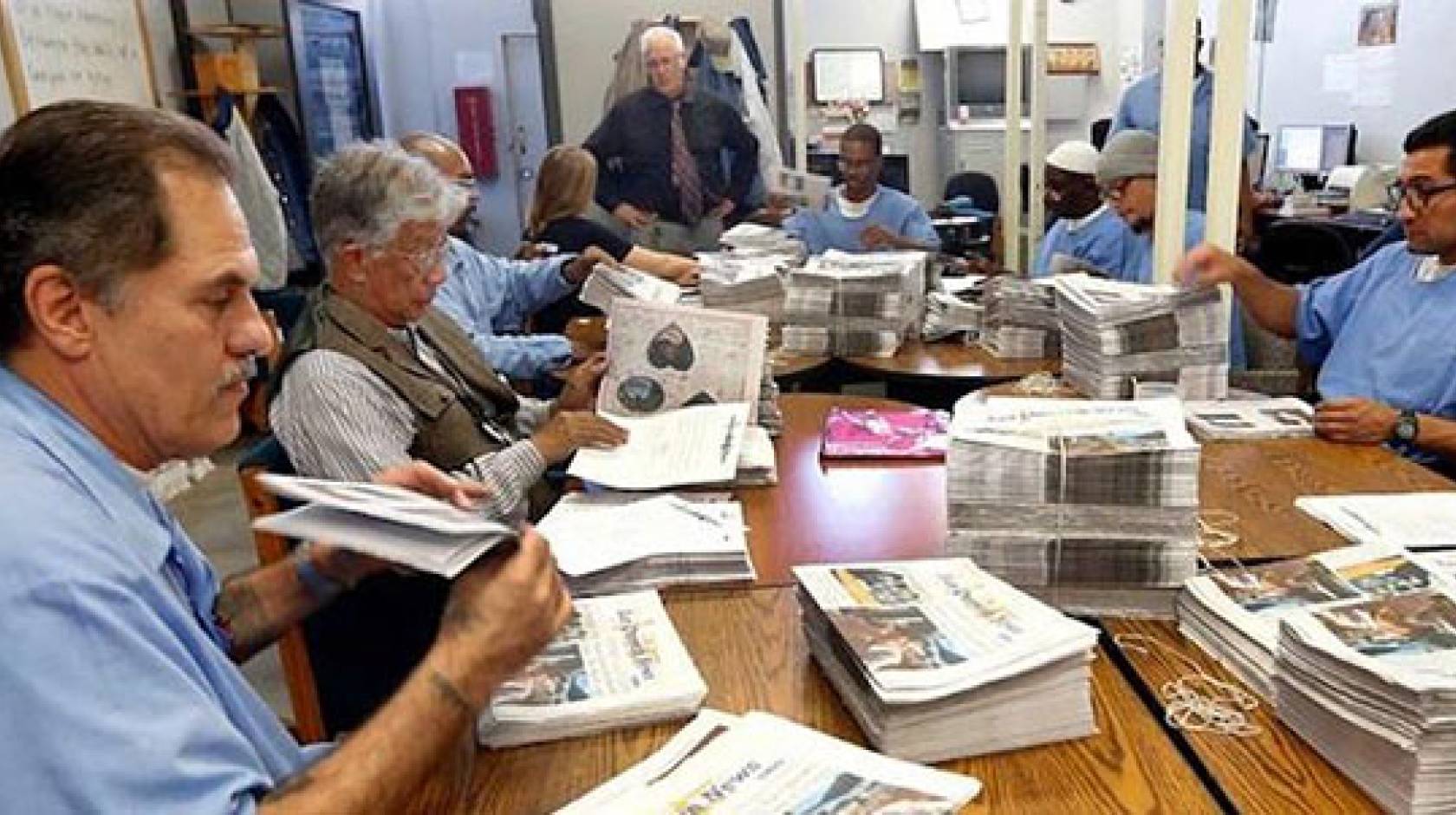

That’s how Drummond ended up in San Quentin. And being behind those stone palisades, he says, changed his life for the better, giving him new hope for both journalism and the human condition. He’s there as an instructor and adviser rather than a prisoner, supervising Berkeley J School students who are teaching inmates working at the San Quentin News on the basics of reporting, writing and editing. But it could have been different; he could’ve been one of the guys identified by a number rather than a name.