Sandra Baltazar Martínez, UC Riverside

UC Riverside Costo Distinguished Professor of American Indian Affairs Clifford Trafzer, served as historical consultant to actor and producer Jason Momoa’s new film, “The Last Manhunt.” The film was purchased last week by the distribution giant, Saban Films.

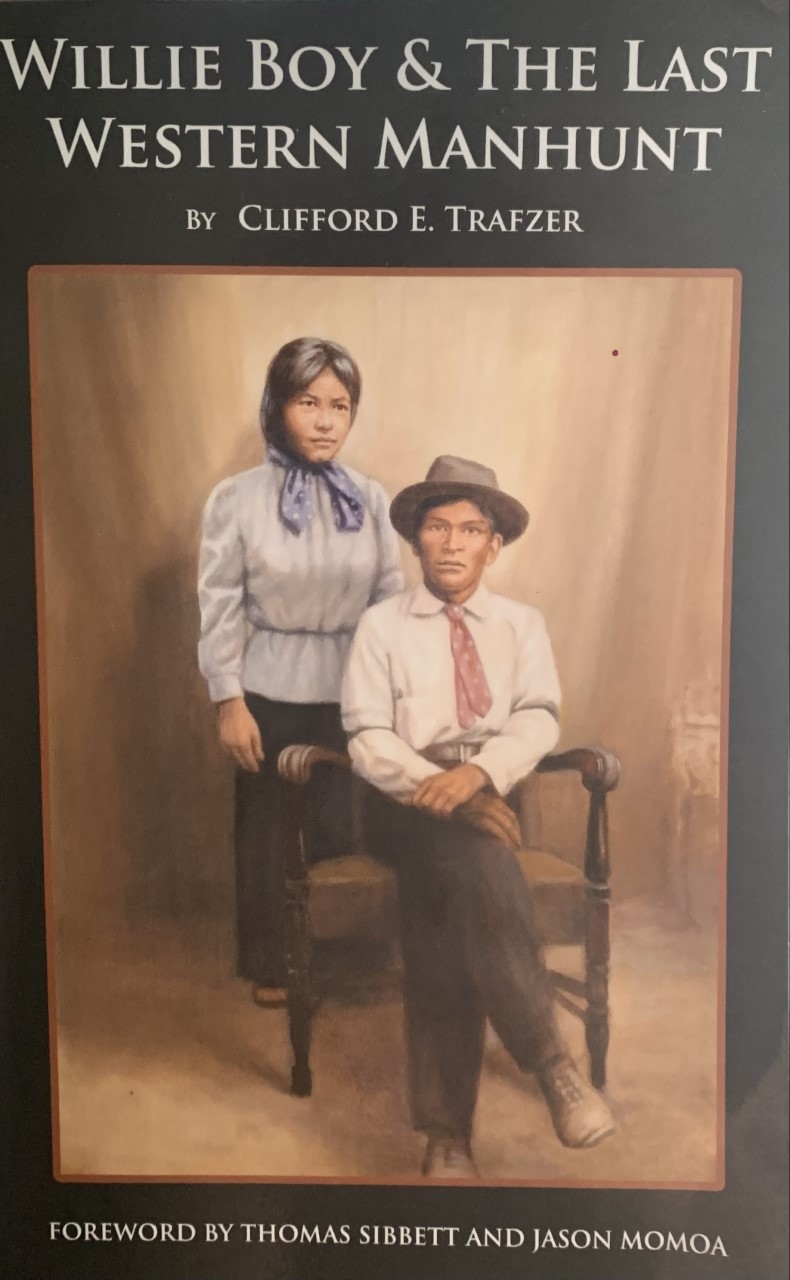

“The Last Manhunt” is based on true events — a love saga between Willie Boy and Carlota Mike, and the death of Carlota and her father, William Mike, the Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians leader. The timeline and facts surrounding this tragedy — along with narratives and on-set images of the film — were published in Trafzer’s 2020 book, “Willie Boy & The Last Western Manhunt.”

The tragedy occurred in 1909 and serves as a setting for the Western film that offers what filmmakers, tribal experts, and tribal community leaders assert is a true account of Willie Boy, a Chemehuevi runner who shot and killed William Mike. It effectively rebuts the historic telling represented in early 20th century newspaper accounts, and in a book and movie versions offered in the 1960s.

Momoa learned of Willie Boy’s story through his visits and conversations with Mojave Desert residents. He then asked his friend, the writer, and producer, Thomas Pa’a Sibbett, to help write the story.

Trafzer has long been telling Native American stories based on first-person accounts and research. As the historical consultant, Trafzer reviewed the script, co-written by Momoa and Sibbett, offered rewrites, and introduced them to other important Native Americans in the region, including Matthew Hanks Leivas. Leivas, like Willie Boy, is Chemehuevi; he is now a tribal scholar, environmental activist, and Salt Song singer.

“This collaboration led to a moving presentation that is not only historically based but captures the emotions of the people and nuanced details of the era and location,” Momoa and Sibbett wrote in the forward for “Willie Boy & The Last Western Manhunt.” “In September 2019, we started shooting the movie at the Gilman Ranch in Banning where Willie Boy had murdered William Mike nearly 110 years to the day of the accident.”

The film took three years to make and was shot in 28 days in Banning and Joshua Tree, a portion of it following the route Willie Boy and Carlota walked as they tried to escape from her father, who disapproved of the relationship because the young lovers were distant relatives. In attempts to escape, the couple walked through the desert for days. The film’s wide-angle shots offers viewers incredible desert scenery.

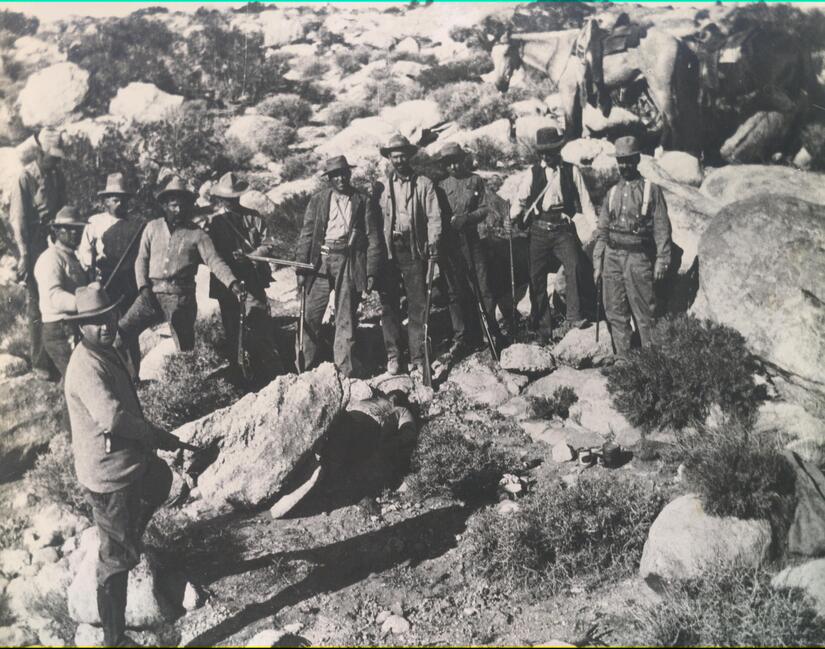

The film’s director, Christian Camargo, said Trafzer’s role was essential in representing the Native American assertion — reflected in Trafzer’s telling — that Willie Boy was never shot and killed by a Riverside sheriff’s posse. At the height of the chase, Trafzer asserts that Willie Boy led the sheriff’s posse and indigenous foot trackers into a canyon where he could have killed all of them but didn’t. Trafzer said that, when the posse finally gave up, an embedded journalist took a group photo of the posse, showing the alleged body of Willie Boy laying on the ground, obscured by a rock. The dead man appeared to be a heavyset person, whereas Trafzer said Willie Boy was thin. And the photograph doesn’t show Willie Boy’s face — deputies said it had been disfigured by a wild animal.

“We are talking about 1909, when headhunters took photographs of dead outlaws — showing their face — to prove they had done the job. Nothing like that happened with Willie Boy,” Trafzer said. “Willie Boy was not a murderer. He was an excellent shooter. He could have killed them all but didn’t. The reality is that people in town were going crazy with the idea of ‘an Indian murderer on the loose’ and they couldn’t come back empty-handed. The sheriff never showed up; he sent a deputy to do the job.”

“The Last Manhunt” premiered at the Palm Springs Art Museum in Palm Springs on May 25, 2022, as part of this year’s Pioneertown International Film Festival. In the audience was Leivas, Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indian residents, Mike family descendants, and other tribal community members.

“We hope we bring truth to this story, and healing,” said Leivas minutes before the premiere. A few of the night’s speakers agreed with Leivas and made reference to the 1969 film starring Robert Redford and Robert Blake, “Tell Them Willie Boy is Here,” which they said fictionalized Willie Boy and the events surrounding the 1909 tragedy.

In addition to consulting on period housing, attire, and language, Trafzer spoke with Leivas about the importance of an authentic representation of the Salt Singers, the group of men who only sing at funerals and together offer a Chemehuevi Ghost Dance to the departed. These songs are a farewell, encouraging the soul to leave in peace. Leivas and Trafzer said that performing the Ghost Dance was a way to offer closure to this now 113-year-old story and to Willie Boy’s soul. It’s the first time this group of Salt Singers allowed their ceremony to be recorded for public view.

“Professor Trafzer was our connective tissue to the tribes and story,” said Camargo, an actor known for his roles in “National Treasure: Book of Secrets,” “The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn” part 2, and “The Hurt Locker.” “He introduced us to Matt Leivas and the Chemehuevi Salt Song singers, initiating a sequence of events that allowed us to tell the story. If it weren’t for him this movie would not have happened.”

"Willie Boy & The Last Western Manhunt" by Clifford E. Trafzer.